Edward Henry Fahey (1844-1907), The Via Massala, Rapallo, Italy. Image from ArtUK, Museums Sheffield.

Our lace ‘Grand Tour’, which we mentioned in the previous post, is not unique. Around 1900 quite a few travellers, especially Americans, explored in turn the various centres of European lacemaking. For instance, Florence G. Weber, who taught lacemaking at the Society of Arts and Crafts of Boston, took a tour through Italian and Belgian lace districts at the beginning of the twentieth century. She reported on her findings in the American publication The Craftsman in 1903. Her first stop was Santa Margherita, a coastal town about twenty miles south of Genoa, where she encountered lacemakers at work under the arcades which protected them from the sun.

After you watch [a lacemaker] a few minutes, she will rise from her work, disappear into the house only to reappear at once with a finished scarf of glistening white silk. This she silently unfolds with a touch so loving that it at once becomes to you a precious thing. Then, this Margherita proceeds to adorn her pretty head with it. As she quickly draws it about her throat she smiles and says: ‘For the teeater’. No French milliner ever adjusted a Paris hat with more convincing skill. You see the scarf, the beguiling smile and the lovely face. The combination is irresistible. You buy the scarf.[1]

Postcard of lacemakers in the shade of the arcades, Santa Margherita

By 1900 Santa Margherita and the surrounding lacemaking towns of Portofino and Rapallo had become major tourist destinations. Italy had long been favoured by rich and cultured travellers, but the possibility of tourism to the Italian Riviera was greatly increased by the arrival of the railway in 1868, a few years after Italian unification. Cultural giants of northern Europe – including Nietzsche, Jean Sibelius, Max Beerbohm and W.B. Yeats – came here to winter; Erza Pound would settle in Rapallo, and Elizabeth von Arnim wrote her novel Enchanted April (1922) about Portofino.[2] Northern Italians also came here for the climate and the sea air: the diplomat Constantino Nigra, Cavour’s right-hand man during the unification of Italy, retired to Rapallo. His villa now houses the local lace museum, which is in the process of reopening after a hiatus. The whole region was transformed by an influx of rich and often titled visitors, and the proliferating infrastructure of hotels, villas, restaurants and other services they required.

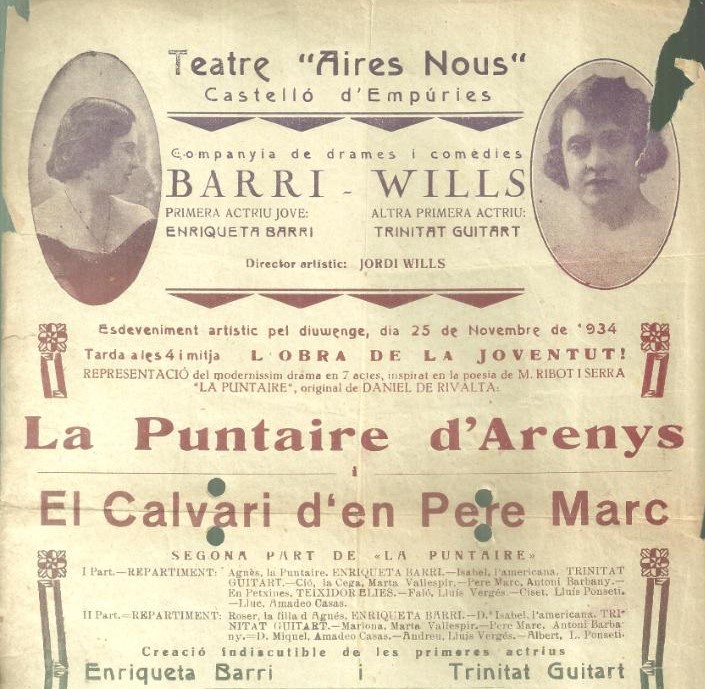

Which brings us back to lace. There is a strong correlation between the survival of handmade lace in the late nineteenth century and the development of tourism, particularly high-end tourism. We mentioned this in our last post about Arenys de Mar; we also see it in the revival of Burano and Palestrina lace in the Venetian lagoon, we see it also in the relations between the spa towns of the Auvergne such as Vichy and the nearby Velay, or the spa towns of Bohemia and the lace regions of the Erzgebirge, we see it again in turn-of-the-century Ostend and Bruges… One can even see it, to an extent, in England, with such initiatives as the Winchelsea lace revival.

The lacemaker – working on the streets with her decorated pillow and bobbins, and wearing local costume – was one of the picturesque attractions these destinations had to offer, and so they feature on railway posters, postcards and tourist literature. But while picturesque, the lacemaker (and her imagined partner, not only in Italy but in Flanders and Normandy, the fisherman) grounded the tourist in a more authentic economy of production, not one tied only to the needs of tourists. Because lacemakers (and fishermen) were so visible on the streets, and indeed on the beach, visitors could interact with these representatives of the local culture, with its particular crafts and traditions which long preceded the arrival of the railway and the hotels. Tourists could spend their money in the expectation that they were supporting hardworking locals, the genuine exponents of a distinct regional culture, and thus ensure the survival of a handicraft that, in Weber’s words, was ‘so refining, so ennobling’.

Postcard of lacemakers on the beach, Portofino

In the case of the Ligurian Riviera south of Genoa, and specifically the Gulf of Tigullio from Portofino to Lavagna, lacemaking was mentioned as a draw in much of the tourist literature of the nineteenth century. John Murray’s Handbook for Travellers in Northern Italy (first published in 1842) states that ‘the manufacture of lace is carried out’ in Rapallo.[3] A rival publication, Dudley Costello’s Piedmont and Italy, from the Alps to the Tiber (1861), reported that the town’s ‘houses being almost all built on arcades, beneath which a numerous population of women and girls industriously ply their trade, – lace-making being the speciality of the town’.[4]

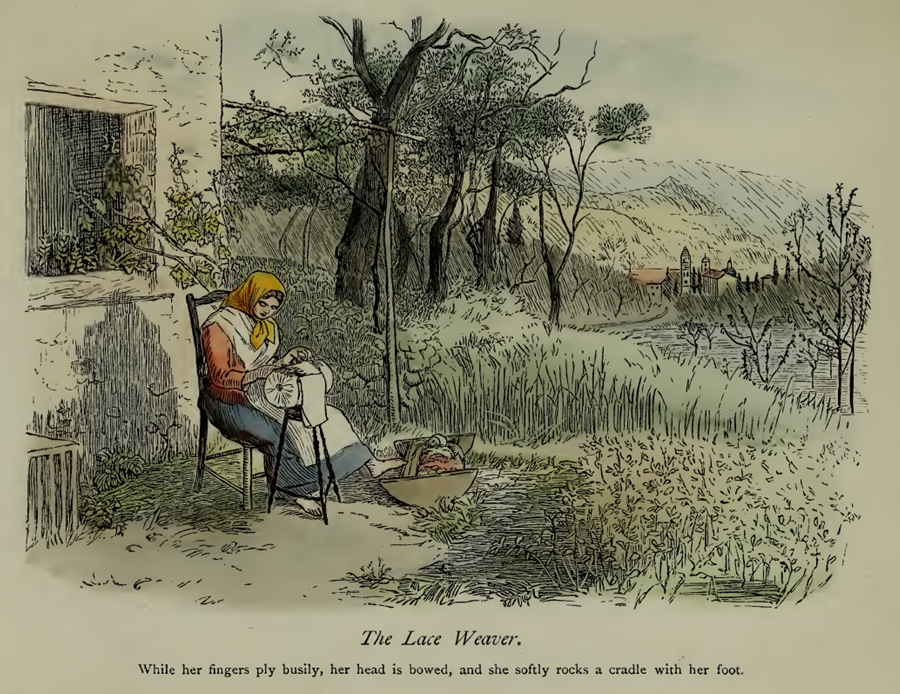

In addition to these guidebooks, another genre of travel writing flourished in the Victorian and Edwardian period, in which English (or anglophone) visitors described their experiences of Italy and the Italians, often accompanied by sketches and watercolours.[5] The first of these to cover the Italian Riviera (to our knowledge) was Alice Comyns Carr’s North Italian Folk (1877), illustrated by Randolph Caldecott. Carr is best known these days as Ellen Terry’s costume designer, but she grew up in Genoa as the daughter of the resident Anglican clergyman, and so knew this part of Italy well. Lacemakers feature in her descriptions of Santa Margherita and Portofino, and she also dedicates a whole chapter to describing a lacemaker’s life. A generation later, the art critic and translator George Frederic Lees published Wanderings on the Italian Riviera (1912), this time illustrated with his own photographs. Again, the lacemakers of Portofino are featured, because:

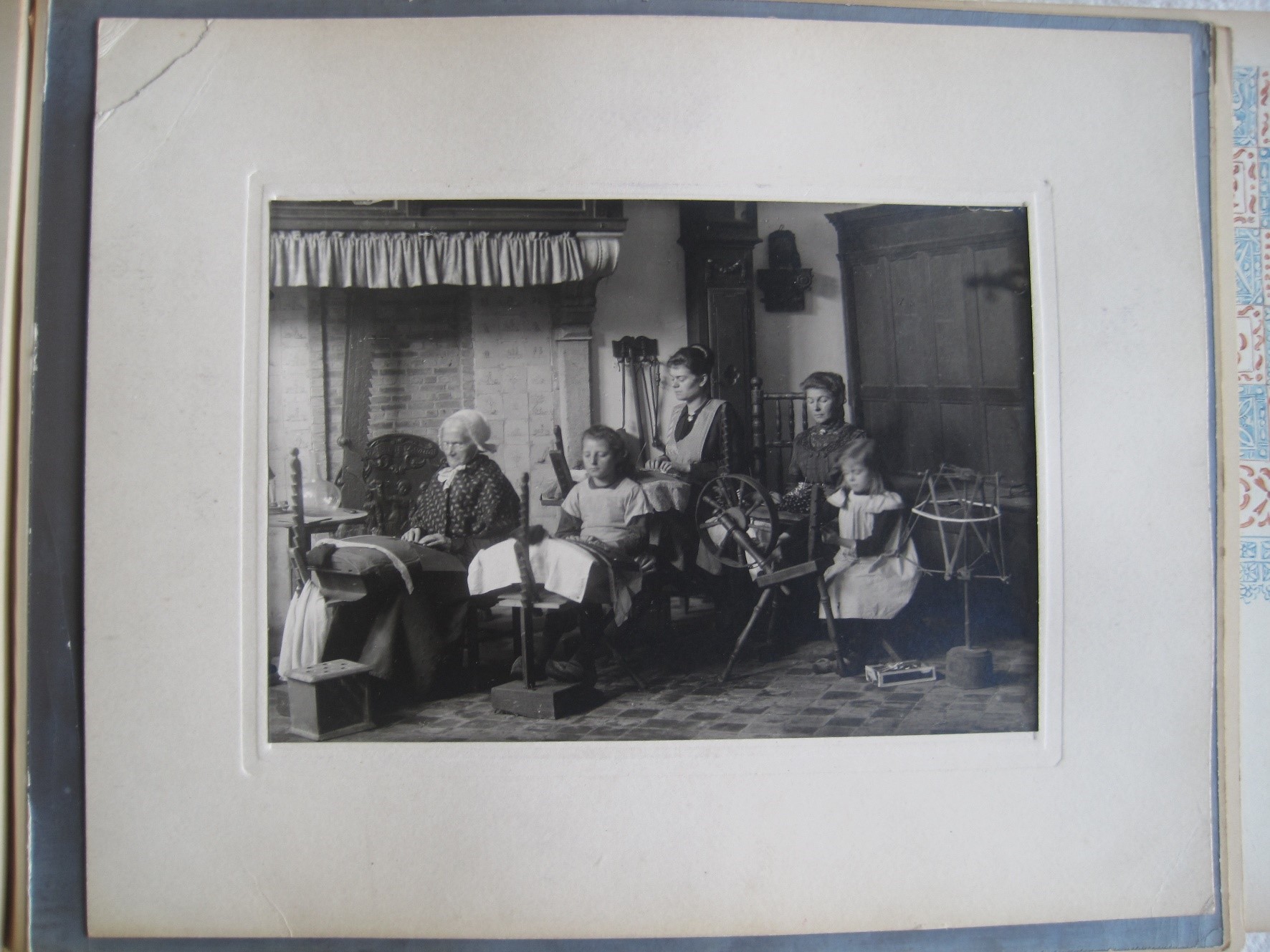

This artistic occupation adds in no small measure to the picturesqueness of the village. Under the arches of the porticoes and at many of the street doors the workers from little girls of six to wrinkled dames of seventy sit in front of the three-legged stands which support the pillows on which their work is produced, and on all sides you hear the click of their wooden bobbins.[6]

All of these authors, Carr and Lee as well as Weber, emphasise that the traveller can – and perhaps should – form a connection with the lacemaker. As we’ve seen in legends of royal patronage of lace, the social divide between rich and poor, the leisured and the sweated, could be ameliorated if the former undertook to directly support the latter. Although there were lace merchants and lace shops in all these towns (and indeed one still exists in Rapallo – Emilio Gandolfi’s), it was this direct relationship between consumer and producer that introduced a moral element to the tourist economy. Carr’s lacemaker Lucrezia, wife of a fisherman, is visited in her cottage by ‘one of the ladies from the palazzo on Santa Margherita’s beach’. And as ‘a private customer buys at double the price offered by Genoa shops’, Lucrezia brings forth her ‘handsome store of completed lace’, even though some of it is already promised to the lace merchant. ‘There are lengths of all widths, in flounce and edge, and insertion-lace; there are scarves and shawls, and parasol covers, and every kind of female adornment that is in fashion’. The Marchesa buys five metres of black silk flouncing (which, given that Lucrezia completes about five inches a day, represents a very substantial contribution to the household income).[7]

Randolph Caldecott’s illustration of Lucrezia the lace-weaver of Santa Margherita, for Alice Comyns Carr’s North Italian Folk, 1878

Lee’s later experiences of Portofino echo those of Weber:

During the season for visitors, the streets are hung with lace; stalls, bearing every article of feminine adornment that can be made on a tombola [pillow], are erected on the piazza and at all the points where prospective buyers are likely to pass; so that how to get by without stopping to admire and purchase becomes a most difficult problem. The fair young lace-makers invite you with such pleasant smiles and in so sweet a voice ‘merely to look’ that it seems unmannerly to hasten away without accepting the invitation, and when you find that the price of their beautiful work is less than would satisfy the most unskilled of city toilers, you rarely resist the temptation to buy lace collars and handkerchiefs for your friends across the seas.[8]

However, once the tourist had made her purchase, how was she supposed to get her lace back home? Lace bought direct from the producer might seem like a bargain, but in part this was because the consumer had yet to pay the duty levied on lace at the border. And this brings us to another aspect of the lace business which we’ve skirted up until now – its role in the black economy. Eminently respectable and usually law-abiding citizens, persons who in every other circumstance would expect their own economic interests to be protected by the state and its agents, had no qualms about smuggling lace. Mild law-breaking was itself an aspect of the more relaxed habits of holiday life. Another artist who spent the winter of 1913/14 in Santa Margherita reported these stories of his fellow guests:

The Russian ladies were also about to return to their country and seemed exercised in their minds as to how they could smuggle their purchases through the customs. There was no lack of suggestions from the other guests. The thinner lady was advised to wind the lace garments, and other pliable goods, in bands round her person, which, if artfully done, would, if possible, improve her figure as well as keep her warm on her journey; care, of course, to be taken not to be so stout as to excite the suspicions of the customs officials. Lady smugglers are now much handicapped by their narrow skirts; neat things in Paris shoes could formerly be negotiated beneath the ample garments of a past fashion. In the days of the bustle I heard of a clock being carried inside that aid to beauty, and it would have passed the customs unnoticed had not the ticking excited suspicion. The soles of boots were rubbed on the pavement to make believe that they had been worn, even water-colour stains were hinted at, as being easily washed out, and would help to pass some parasols.

A German described a scene he had witnessed at the frontier of his country. There were three passengers beside himself in his compartment, two ladies and a gentleman. The former expressed their fears as to the way they had hid their lace, and the latter assured them that if they folded it carefully it could all be pinned inside their hats, and that the customs officials would not look there. They did as instructed, and on arriving at the frontier an official entered the compartment to examine the hand baggage. Everyone said that they had nothing to declare, and a superficial look at the ladies’ hand-bags satisfied the officer, who after this was about to examine a portmanteau of the male passengers. But imagine the horror of the ladies when they saw their pretended friend touch his head with his finger and with a wink of the eye point to their hats. The official at once ordered the ladies to take them off, and, on discovering the lace, they had to follow him to the customs office, where they were mulcted in a fine and the lace was confiscated. After they had all safely passed the frontier, the man who had acted so strangely, to say the least of it, begged the ladies to allow him to recoup them to the amount of their fine, and as for the lace, he said, ‘You are welcome to six times what you have lost.’ Then opening his portmanteau he said, ‘Take what you want — the mean trick I played on you has enabled me to smuggle more than a thousand pounds’ worth of lace through the customs.’[9]

Lacemakers could still be found working on their pillows under the arcades and on the beaches of Santa Margherita and Portofino in the 1930s and 1940s, as can be seen in these newsreels from Istituto Luce. Alongside the women are displays of their product, still attracting the rich and fashionable visitors to the Italian coast.

Hermann Fenner-Behmer (1866-1913), Lacemakers on a street in Rapallo, 1909

(The works by Carr, Lees, Tyndale and Florence Weber are all freely available on Internet Archive.)

[1] Florence G. Weber, ‘Lacemakers’, The Craftsman 4:6 (1903): 486.

[2] On this history see Lauren Arrington, The Poets of Rapallo: How Mussolini’s Italy Shaped British, Irish, and US Writers (Oxford, 2021)

[3] Handbook for Travellers in Northern Italy 4th edition (London, 1853), p. 143.

[4] Dudley Costello, Piedmont and Italy, from the Alps to the Tiber (London, 1861), p. 100.

[5] Ross Balzaretti, ‘Victorian Travellers, Apennine Landscapes and the Development of Cultural Heritage in Eastern Liguria, c. 1875-1914’, History 96:4 (2011): 436-58.

[6] Frederic Lees, Wanderings on the Italian Riviera (Boston, 1913), pp. 275-6.

[7] Alice Comyns Carr, ‘The Lace Weaver’, in North Italian Folk (London, 1878), pp. 97-103.

[8] Frederic Lees, Wanderings on the Italian Riviera (Boston, 1913), pp. 276-7.

[9] Walter Tyndale, An Artist in the Riviera (New York, 1915), pp. 65-7.