We’ve been on a bit of a lace grand tour over the last year – Catalonia, Val d’Aoste, Liguria, Idrija, Annaberg – mostly visiting museums with collections of lace and their enthusiastic curators such as the one at Arenys de Mar. One thing we’ve noticed in our wanderings is the large number of public monuments dedicated to lacemakers. We’ve encountered one before on this site, albeit only in passing, at the base of Eugène Deplechin’s monument to the songwriter Alexander Desrousseaux in Lille. Another French statue can be found outside the railway station in Issoire. There are several in Italy, at least three in Portugal, and a couple in Brazil. But there seems to be a particular concentration in Catalonia where we’ve counted nine. Here’s our list, in order of the year they were erected (where known).

1. Barcelona, Montjuïc gardens, ‘A la puntaire’, by Josep Viladomat i Massanas, erected 1972. Picture Wikipedia Commons

2. Sant Boi de Llobregat, ‘La puntaire’, by Artur Aldomà Puig, erected in 1999. Picture Patrimonio de Sant Boi de Llobregat

3. Arenys de Mar, ‘A la puntaire’, by Cèsar Cabanes Badosa, erected in 2003.

4. Arenys de Munt, ‘A la puntaire’, by Etsoro Sotoo, erected in 2003. Picture Wikipedia Commons

5. L’Arboç, ‘A la puntaire’, by Joan Tuset i Suau, erected in 2005. Picture Wikipedia Commons

6. Martorell, ‘A la puntaire’, by Gonzalo Orozco, erected in 2006. Picture Mapes de Patrimoni Cultural, Diputació Barcelona

7. Monistrol de Calders, ‘La Puntaire’, The statue is dated 1995, but its installation was sometime between 2016 and 2019. We’re not sure who the sculptor was. See Mapes de Patrimoni Cultural

8. Salou, ‘A las puntaires’, by Natalia Ferré, erected in 2019. Picture Municipality of Salou

9. Sant Marti de Tous, ‘La Puntaire’. We’re not sure of the name of the sculptor nor the date of installation. Picture from the online Catalan database ‘Mapes de Patrimoni Cultural’

Looking at the dates, it would seem that the lacemaker is a fairly recent monumental addition to the urban landscape, with the majority only erected in the twenty-first century. However, in at least one case her story goes back considerably further. This is the statue in Arenys de Mar, once a significant port but now primarily a seaside town about 40 kilometres north of Barcelona. This is the only statue to which we can give a name: she is Agnès and her story helps explain the prominence of monumental lacemakers in the region.

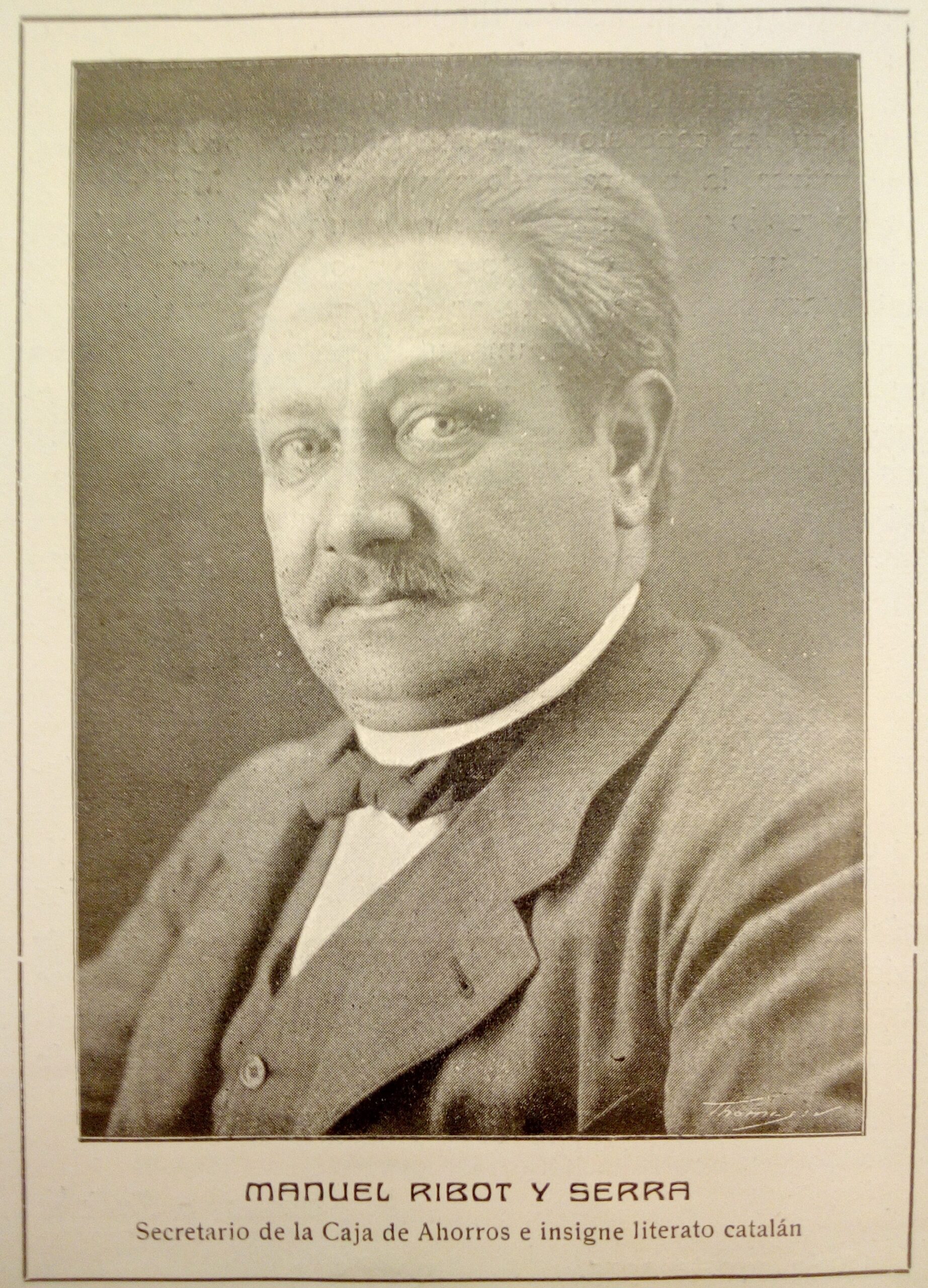

The origins of ‘Agnès the lacemaker’ lie in a poem composed in 1885 by Manuel Ribot i Serra (1859-1925). Ribot was the librarian and archivist of Sabadell, a burgeoning industrial city close to Barcelona. He was also a poet and playwright, and a participant in the Catalan language and cultural revival of the second half of the nineteenth century, which goes under the general title ‘La Renaixença’. A key institution of the Catalan revival was the regular ‘jocs florals’ [floral games], poetry competitions akin to an eisteddfod. In July 1885 Arenys de Mar, which was fast becoming a favourite holiday resort for the Catalan middle classes, hosted some floral games in which Ribot competed. The theme for his poem ‘La Puntaire’ [the lacemaker] was suggested to him by a friend, Marià Castells i Diumeró (1834-1903), who was a lace merchant in Arenys.[1] The Castells family business was at the forefront of the renewal of handmade lace as a luxury product in nineteenth-century Spain, and the firm’s products are well represented in the local museum’s collection of lace. Ribot’s work went on to win the ‘flor natural’ for the best love poem.

Manuel Ribot i Serra, author of ‘La puntaire’. From the Sabadell history website

Marià Castells i Diumeró (1834-1903), founder of the Castells lace house in Arenys de Mar. From the exhibition catalogue Els Castells, Uns Randers Modernistes, Museu Arenys de Mar, 2007

Agnès’ story, however, is not necessarily a great advert for the lace industry. She was betrothed to a sailor who, to make his fortune, sets off for Cuba (then part of the Spanish Empire) with promises of fidelity. She waits and weeps by the shore. Five years later the sailor returns from ‘America’, rich but married. His ‘American’ wife orders a christening gown from Agnès who, to support her blind mother, is obliged to accept the commission. (Although this is not tackled directly in the poem, through his marriage the sailor has also forsaken his language community, for the ‘American’ would have been a Spanish-speaker.) On the day of the baptism Agnès, worn out by poverty and heartache, dies.[2] The poem offers a twist on the theme of the lovelorn lacemaker who makes a bridal veil for her rival which becomes her own burial shroud. Recurring lines in the poem – ‘a fent les puntes pels rics / perquè ella és pobra’ [making lace for the rich / because she is poor] – also echo sentiments that we have encountered before in the literature of lace, for instance in the play Elisa de Kantwerkster by Frans Carrein.

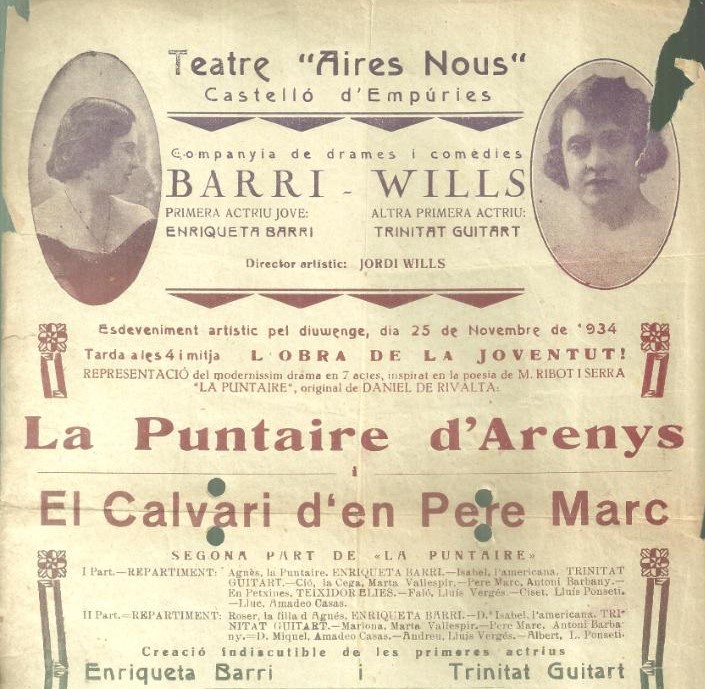

Ribot’s poem would have many afterlives. Set to an existing melody – ‘Els contrabandistes’ [the smugglers; the same tune is also used for the famous Catalan carol ‘El cant dels ocells’, the song of the birds] – it would become a popular as a song.[3] But Agnès’ fame really took off nearly half a century after her initial outing, when the poem became the basis for a popular novel by Lluis Almerich i Sallarés (1882-1952), who wrote under the pseudonym ‘Clovis Eimeric’. Eimeric’s La Puntaire (the lacemaker, 1926) drew on Ribot’s storyline and even included the poem in the book. It was not only Eimeric’s greatest success as a novelist, it was also one of the most widely read books in Catalan in the inter-war period.[4] It was immediately converted into a Catalan language stage play by numerous imitators. The best known (and occasionally revived) was La Puntaire de la costa [the lacemaker of the coast] by Tomàs Ribas i Julià (1894-1949). However, there were other versions by Ramon Campmany (1899-1992), Salvador Bonavia I Panyella (1907-59), Lluis Milla i Gacio (1865-1946) and Joaquim Montero I Delgado (1869-1942). Although they go by slightly different titles, all of these authors acknowledged their debt to Ribot (and sometimes to Eimeric). Eimeric himself, I believe, also dramatized the work. In 1928 there was even a film La Puntaire, directed by José Claramunt. Eimeric wrote a sequel, and this too (or alternative sequels) would be turned into stage plays.

Clovis Eimeric, La puntaire (1926 novel)

Tomàs Ribas i Julià, La puntaire de la costa, first produced 1927.

Salvador Bonavia I Panyella, La puntaire (1926).

Ramon Campany, La puntaire, first performed 1927, published 1933.

Lluís Millà i Gàcio, La Puntaire catalana (1929)

Joaquim Montero, La Cançó de la Puntaire, performed 1930.

Daniel de Rivalta (another pseudonym of Clovis Eimeric?) La puntaire d’Arenys, performed 1934

José Claramunt dir., La Puntaire (1928 film)

It was this success that inspired the sculptor Cèsar Cabanes i Badosa (1885-1952) to produce a statue based of Agnès. Cabanes was born in Arenys and, though he then lived in the city of Terrassa near Barcelona, he retained close ties to the seaside town. He mounted an exhibition there in 1929 where he displayed a terracotta model of ‘Agnès, la puntaire’. He chose to depict the poem’s first lines:

| A la voreta del mar, l’Agnès se’n va a treballar, quan l’alba apunta; i sos ulls, en plor desfet, va mullant lo coixinet on fa la punta. |

By the edge of the sea Agnes goes to work As dawn breaks; And her eyes weep uncontrollably, Dampening the pillow On which she makes lace. |

‘Agnès, la puntaire’ in terracotta, by Cèsar Cabanes Badosa, 1929. This version of the statue is in the Museum of Arenys de Mar.

The figurine was clearly admired because the Town Council commissioned another sculptor, Josep Miret, to complete a version in marble, intending to erect it in a public ceremony on 9 July 1930, the festival of Arenys de Mar’s patron, Saint Zeno. However, due to a change in local government, the plan was shelved and then forgotten during the civil war and its aftermath.

The model for ‘Agnès, la puntaire’ by Cèsar Cabanes Badosa, from the museum catalogue Cèsar Cabanes Badosa, Retorn a casa (Arenys de Mar, 2010)

It was not until 1957 that the Council returned to the project, only to discover that, in the meantime, Miret had used the marble for another statue. And so the plan languished again until 2001 when a local initiative, ‘L’Associació Amics de la Puntaire’ [the Society of Friends of the Lacemaker], decided to raise funds to translate the statue into bronze.[5]

Agnès was finally erected on 16 March 2003, the feast of Saint Ursula, yet another patron of lacemakers. And this is where we found her, looking out to sea and waiting for her sailor lover, in October 2021.

Even at the time of her greatest success there were critics of the vogue for lovelorn lacemakers. In the magazine The actor and playwright Enric Lluelles attacked the several play versions that were then (August 1930) competing with each other in town and village theatres across the province. The lacemaker represented a downtrodden, passive version of Catalan womanhood, a martyr for love. Although he approved of bringing drama to the people, in their own language, if it offered only a sentimental and weak ideal of the people, then it would do more harm than good. It was time, he wrote, to create a new version of the working-class Catalan woman ‘with a firm, resolute and well-balanced character, and to replace these seven tearful lacemakers with lacemakers of flesh and blood, healthy and radiant, their skin tanned by the rays of the sun and the salt seas of the Mediterranean, who work at their pillows with relaxed eyes and laughter on their lips’.[6]

While the fashion for lacemaker statues in Catalonia must owe something to the lingering impact of Ribot’s and Eimeric’s ‘Agnès’, we suspect the sculptors also intended to convey something of this ‘flesh and blood’ lacemaker, one who suffered no doubt, but who also survived, and passed on her craft to the next generation. It’s noticeable, for example, that all the other statues imagine the lacemaker at work, a more tangible contribution to Catalan society, economy and culture than the tears of Cabanes’ ‘Agnès’.

[1] On the Castells family see the exhibition catalogue Els Castells, Uns Randers Modernistes, Museu Arenys de Mar, 2007.

[2] For the full text see: http://marisa-connuestrasmanos.blogspot.com/2010/08/la-puntaire-de-manuel-ribot-i-serra.html

[1] The website Càntut: Cançons de tradició oral, provides access to five different recordings of ‘La puntaire’.

[4] Núria Pi I Vendrell, Bibliogafia de la novel.la sentimental publicada en Català, entre 1924 i 1938 (Barcelona, 1986), p. 83.

[5] This information is taken from the exhibition catalogue, Cèsar Cabanes Badosa: Retorn a casa (Museu d’Arenys de Mar, 2010).

[6] Enric Lluelles, ‘Set Puntaires’, Mirador : setmanari de literatura, art i política, 21 August, 1930, p. 5.