‘Saint Anne and the Virgin Mary’, copy of work by Giovanni Antonio Galli, known as ‘lo Spadarino’. Sold at Christies in 2010.

Saint Anne’s day falls on 26 July. As we know, lace has many patron saints but, in West Flanders, Saint Anne was particularly fêted. According to the apocryphal gospels Anne was the mother of Mary. It was she who dedicated Mary to the service of the Temple where the future Mother of God wove the veil which, as we have seen, is a textile of some importance in the legendary history of lace. In Catholic iconography Anne is usually depicted teaching Mary to read the scriptures, but sometimes she is shown training her daughter in needlework, weaving and embroidery; Mary was exercising these domestic skills at the very moment she was visited by the angel Gabriel, hence the basket of linen beside her in depictions of the Annunciation. Anne was, therefore, a suitable patron for seamstresses and everyone involved in the needle trades, whose skills and heritage were passed on from mother to daughter. Flemish lacemakers were more likely to be trained in lace schools than at home, but these too provided a female-led pedagogical environment. In Bruges, Poperinge and Bailleul, lace schools celebrated Saint Anne’s Day.

Jan-Frans Willems (1793-1846), ‘Father of the Flemish Movement’. Unknown C19 painter. From Wikipedia Commons.

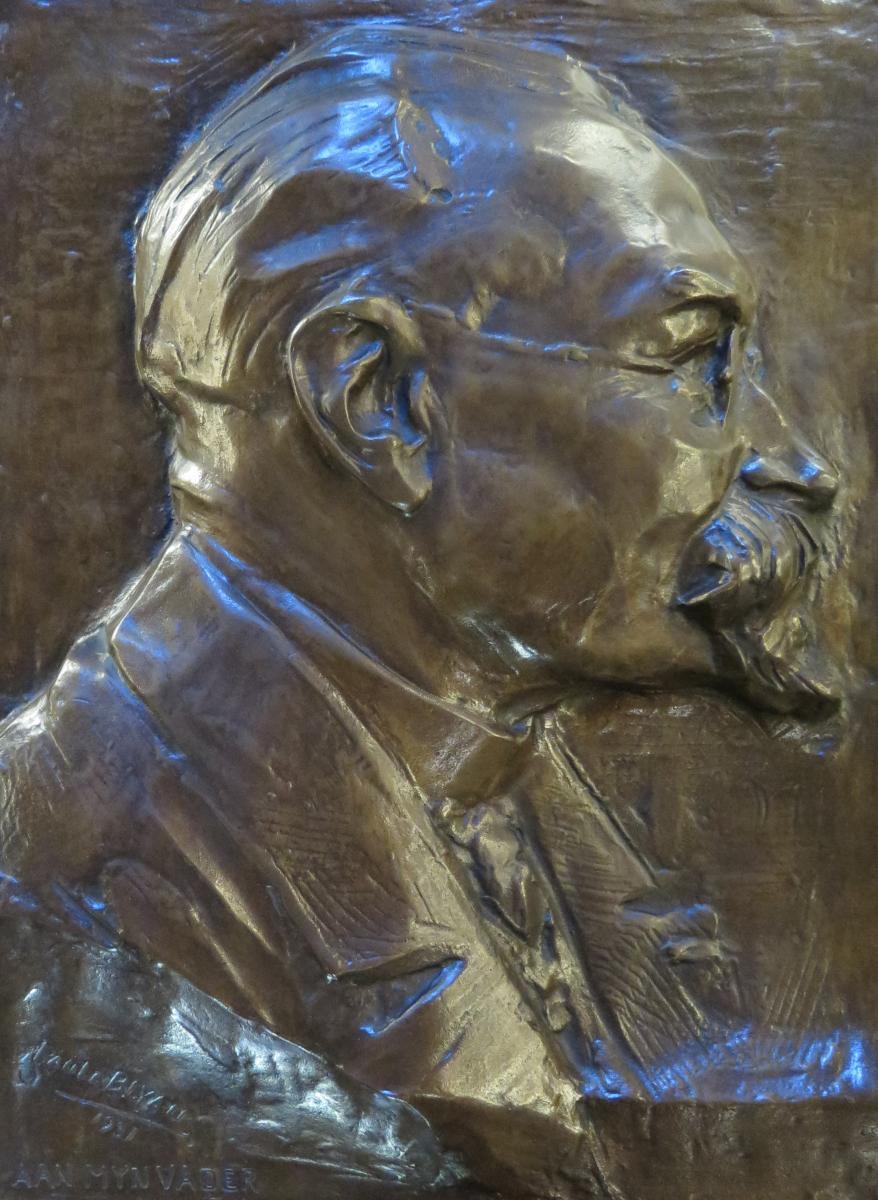

We know of this tradition indirectly, from the attempts to record lacemakers’ songs. The first person to draw attention to the lacemakers’ musical cult of Saint Anne was the philologist Jan-Frans Willems (1793-1846), known as ‘the Father of the Flemish Movement’.[1] Willems sought to defend the imperilled position of Dutch within the new Belgian state by demonstrating that it too was a literary language with a noble history, but he also emphasised the moral qualities of one’s ‘mother-tongue’. Knowledge and traditions – culture in other words – were passed on from mother to her nursing child. One of the primary vehicles for both literary and popular traditions were songs. Songs had taken on a huge significance as expressions of national thought and feeling in the romantic period. Willems’ final – indeed posthumous – publication was Oude Vlaemsche Liederen ten deele met de melodieën (Old Flemish Songs, some with melodies), which was completed in 1848 by his friend Ferdinand Snellaert (1809-1872). At the very end of this volume Snellaert included two lacemakers’ songs in honour of Saint Anne.[2]

‘Het vlaamsche lied’ (Flemish song). Relief adorning Isidoor de Rudder’s monument to Jan-Frans Willems in Ghent.

‘t Is van dage Sint Anna-dag,

Wy kijken al near den klaren dag,

En wy kleên ons metter spoed,

Om te gaen ter kerke toe.

Als de misse wierd gedaen

Wy zijn al blijde van deure te gaen.

Josephus is gekomen al hier

Met zijnen wagen en zijn bastier: |

Today is Saint Anna’s day,

We look out for sunrise,

And we dress ourselves with haste,

To go to church.

As soon as the mass is over

We are glad to get outside.

Josephus is already there

With his wagon and its cover: |

De provianden,

Koeken in manden,

De provianden

Dragen wy meê. |

The provisions,

Cakes in baskets,

The provisions

We’ll take with us. |

Die willen met onzen wagen meêgaen

Moeten ‘t geheel jaer hen mestdag doen;

En die ‘t niet en hebben gedaen,

Moeten ‘t huis blijven en niet meêgaen. |

Those that want to go in our wagon

Must have completed their daily tasks

through the whole year;

And those who haven’t,

Must stay at home and not come along. |

Sint Anna-dag is deure,

‘k Ben mijn geldetje kwijt;

Nu zit ik hier en treure

Met kleinen appetijt.

‘K En heb geen zin van werken,

Het werken doet my pijn;

‘k Wilde dat ‘t heele dagen

Sint Anna mogte zijn. |

Saint Anna’s Day is done

I’ve spent all my money;

Now I sit here and lament

With little appetite.

I’m not in the mood for work,

Work makes me miserable;

I wish that every day

Could be Saint Anna’s. |

De schoolvrouw komt te vragen :

Wel duiv’l hebt gy geen zin ?

Een perkment in acht dagen

Is dat geen schoon gewin?

Mijn kussen aen de galge,

Mijn boutjes aen ‘t perlorin.

‘k Wilde dat ‘t heele dagen

Sint Anna mogte zijn. |

The school mistress comes and asks:

Hell’s bells, you’re not in the mood?

A pattern in eight days

Is that not a decent wage?

My cushion to the gallows,

My bobbins to the pillory.

I wish that every day

Could be Saint Anna’s. |

These two songs had been sent to Willems in October 1841 by Edmond de Coussemaker, a lawyer, musician and a fellow enthusiast for all things medieval, who wrote to him from the Flemish-speaking corner of France known as the Westhoek.[3] Although then living in Douai, Coussemaker had collected the Saint-Anne songs from the lace schools of his native Bailleul (or Belle to give the town its Flemish name). In 1852, Coussemaker was moved to start collecting songs again, prompted by the new French government’s sudden enthusiasm for folk music, and its simultaneous desire to eradicate regional languages such as Flemish, which was banned from French schools in January 1853. Shortly afterwards Coussemaker would help found, and then lead, the Comité flamand de France (The Flemish Committee of France) whose motto was Moedertael en Vaderland (Mother-tongue and Fatherland). Coussemaker was not a Flemish nationalist, but he wanted to celebrate the Flemish contribution to French history and culture, and to demonstrate that Flemings too had a literature and a language worth preserving.[4] His most important contribution in this undertaking was his 1856 volume of Chants populaires des Flamands de France (Folksongs of French Flanders). This contains a whole section dedicated to ‘Sinte-Anna-liedjes’, including both the two given above and five more, together with a short description of the festivities arranged in the lace schools that day.

Edmond de Coussemaker (1805-76), lawyer, musician, folksong collector. Engraving by Isnard Desjardins, from the British Museum.

According to Coussemaker, Saint Anne’s Day was,

for the young women who attend the lace schools, just as it was for women of every age who shared this occupation, a feast that was celebrated with every sign of joy. It was a veritable holiday in which the popular muse takes a large part. The evening before Saint Anne’s Day, the schools and workrooms are decorated with flowers and garlands. Early the next morning, all the young women, dressed in their best clothes, come to wish a happy holiday to their lace mistress; then they take themselves to the church, singing all the while. After having heard the mass in honour of their holy patron, they return to the school where a breakfast of cakes is served. The meal over, they get ready for a trip by wagon or coach to a nearby town or village. Sometimes the pleasure-trip goes as far as Dunkirk. Every July one sees, in the streets of Dunkirk or at the seaside, groups of young women from Bailleul, who are recognizeable from the equal simplicity of their dress and their manners. If the weather proves inclement, they pass the day at the school, dancing and singing.[5]

Edmond de Coussemaker, Chants populaires des Flamands de France (1856). Illustration depicting Saint Anne’s Day in the lace schools.

Some of the songs associated with this holiday directly honour Saint Anne, but most concentrate on the associated festivities. From these songs we learn that the lacemakers got up early, drank coffee, went two by two from the laceschool to the church to offer candles to their patron. When in the country they played ‘tir du roy’ (a verticle archery game) and danced with the villagers. But the songs also acknowledge the fleeting nature of lacemakers’ pleasures.[6]

Jonge dochter, en wilt niet treuren,

‘t Is Sint’ Anna die komt aen;

En ‘t zal nog wel eens gebeuren,

En den dag die zal vergaen.

Laet ons dansen, laet ons springen,

Laet ons maken groot plaisier.

En dat met contentement,

Zoo een leven, zoo een eind’. |

Young woman, don’t be sad,

Saint Anna’s Day is coming.

She’ll soon be here

And then the day will be gone.

Let us dance, let us jump,

Let us enjoy ourselves

As much as we can;

Such a life, such an end. |

En Sint’ Anna die gaet deure,

Zy ga naer een ander land:

Eu wy zitten hier en treuren

Met ons geldjen heel van kant.

En wy zitten in de kamer

Met ons kussen op de knien.

Is dat niet een groot verdriet?

Geerne werken en doen ik niet. |

Saint Anne has departed;

She’s gone to another country.

We sit here and lament

All our money is gone.

Here we sit in the workroom

With our cushions on our knees.

Isn’t it a great pity?

I don’t want to work anymore. |

Despite Coussemaker’s reference to the ‘simplicity’ of Saint Anne’s celebrations, there is evidence that things could get out of hand. In 1858, when Bailleul contained ten or more lace schools and almost the entire female population of the town was engaged in lacemaking, the mayor complained about disorders in the street and stipulated that from then on

dances and public merrymaking in the street cannot take place except on the days specially reserved for the celebration of this holiday, and should only include women and children, and no men. These entertainments should not begin before 7 in the morning, nor continue after 8:30 at night.[7]

Such official restrictions may have restrained the celebrations, but a more important factor was the decline of domestic lacemaking; by the first decade of the twentieth century there was only one lace school still functioning, which had just 30 apprentices.[8] Yet they continued to honour Saint Anne’s day. The girls who attended the school run by Euphrasie Roelandt went to mass on that day, and then returned to the school for cakes and hot chocolate. Then the teacher was crowned by her pupils: an enormous floral crown was slowly lowered onto her head while they sang a hymn to ‘Moeder Anna’ [a song present in Coussemaker’s collection]. The identification between the mother of the mother of God and the educator could not be more obvious. Madame Roelandt rewarded each pupil with a five-centime piece. In the afternoon the party walked up to a local beauty spot, the Mont Noir, to hold a picnic.[9] (Mont Noir, or Zwarteberg, was the family demesne of the novelist Marguerite Yourcenar, who has something to say about lacemakers in her memoirs.) In previous years the girls from the lace-schools had also honoured the lace merchants on this day, by dancing round-dances outside their houses (probably in hope of a financial reward).[10]

The children from the Babelaarstraat lace school, Poperinge, run by Zoete Mène (Philomène) Matton (seen on the left), 1906.

Sometimes lacemakers from Bailleul and the surrounding villages met up with their fellows from Poperinge, a few miles away over the border in Belgium. Again, our knowledge of events there largely depends on folksong collectors. We have already consulted Albert Blyau’s collection of songs for information on Kleinsacramentsdag, the Ypres lacemakers’ holiday, but he also attended the lace school run by ‘zoete Mène’ (Philomène Delporte, b. 1845) in the Babbelaarstraat in nearby Poperinge, where they celebrated Saint Anne’s instead.[11] Blyau’s ‘Sint-Annaliedjes’ have relatively little to say about lacemakers’ religious life, but rather concentrate on the fun they intend to have. The repertoire contains a large number of soldiers’ songs because, for working women mired in poverty and domestic responsibilities, the soldier’s life represented an ideal of minimum labour with maximum personal autonomy. In popular culture generally soldiers were compounded with the nobility as a leisured, feckless class, which is what lacemakers aspired to be on their holiday. Some songs also poked fun at ‘kwezels’, a nickname for ostentatiously devout older women, precisely the kind of person who might run a lace-school. In some ways Saint Anne’s celebrations were, like Saint Gregory’s Day in Geraardsbergen or Our-Lady-of-the-Snows in Turnhout, directed at the lace mistresses who might receive floral tributes or other acknowledgements of gratitude from their pupils, but these songs suggest an undertow of resentment.[12]

In Poperinge the festivities lasted two days: the first consisted of an outing to a nearby park but the highlight was the second day, when they went to the seaside. The programme is laid out in one of their songs.

Courage, kinders al te saam,

En Sint-Anna die komt aan !

Wij zullen vroolijk spelen,

En wat dan!

‘t En zal ons niet vervelen :

En wat dink je daarvan ? |

Come on children all together,

And Saint Anna is coming!

We will play merrily

And how!

And we won’t be bored:

And what do you think of that? |

Onze sneuklaar is verkocht

En ons geld is thuis gebrocht.

Wij zullen taarten bakken,…

Van peren en van appels :… |

Our snacks have been bought

And we’ve brought our money home.

We will bake tarts,

From pears and apples. |

Alles is zeer wel bereid

Tegen dezen blijden tijd.

De koeken en de hespe, …

‘t Is alles van het beste : … |

Everything is very well prepared

For this happy time.

The cakes and the ham,

It’s all the best quality |

Eer wij van den tafel gaan,

Wij zijn van alles wel voldaan,

Van éten en van drink en,…

Van tappen en van schinken, … |

Before we leave the table

We’ll be absolutely full

Of eating and drinking,

Drinks from the tap and the jug. |

Maar als den eersten dag komt aan,

‘t Is om naar ‘t Koethof toe te gaan.

Wij zullen vroolijk wandelen, …

Van ‘t eene naar het ·andere: … |

And when the first day comes,

It’s off we go to the Koethof [Castle Couthof, near Poperinge].

We will wander merrily,

From one thing to another. |

Maar als den tweeden dag komt aan,

‘t Is om naar Duinkerk toe te gaan.

Wij zeggen ‘t zonder liegen, …

De scherrebank zal vliegen : … |

But when the second day comes,

It’s off we go to Dunkirk.

We say it without lying,

The charabanc will fly. |

Maar als wij in Duinkerk zijn,

Wij zullen stil. en zedig zijn;

Wij zull’n met goede manieren, …

Onze feestdag wel vieren : … |

But when we get to Dunkirk,

We will be quiet and modest;

We will be well mannered

Celebrating our holiday: |

Couthof Castle, near Poperinge, destination of local lacemakers on Saint Anne’s Day.

The last claim to quiet and modesty may be ironic, given the other song they sang boasted of their ability to make noise. This song, which has been recorded by the Belgian folk groups Sidus and Kotjesvolk, is a powerful expression of local and craft pride, as lacemakers collectively took over the streets of Dunkirk for the day. However, the boast that they made lots of money should be taken with a pinch of salt.

De kinders van de Babbelaarsstrate

Zoûn zoo geern naar Duinkerke gaan,

Om da’ n-hunder dust te laven

En naar Duinkerk toe te gaan.

Zoete merronton, merronton, merronteine !

Zoete merronton, de postiljon ! |

The children from Babbelaarstrate

Really want to go to Dunkirk

And there to quench their thirst

And to go to Dunkirk. |

En wij zull’n de koetsen pareeren

Met de bloemptjes zoet en schoon,

En ons ook wel defendeeren,

G’lijk den keizer op zijn troon.

Zoete merronton, etc. |

And we will decorate the coaches

With sweet, beautiful flowers

And we’ll stand up for ourselves,

Like the emperor on his throne. |

En wij zull’n al omdermeest schreeuwen :

“Vivan van Sint-Annadag !”

En ons ook wel defendeeren :

‘t Is de spellewerkige’s feestdag ! |

And we will loudly cry

Long Live Saint Anna’s Day.

And we’ll stand up for ourselves:

It is the lacemakers’ holiday. |

Maar als wij in Duinkerke komen,

En wij rijen al door de stad;

Iedereen zal buiten komen

En zal zeggen : “Wat is dat ?” |

But as we come into Dunkirk

And we ride right through the town

Everyone will rush outside

And they’ll say: ‘What’s going on?’ |

“ ‘t Zijn de Poperingschenaren,

Die daar komen met geweld;

En ze werken heele jaren,

En ze winnen vele geld !” |

It’s the girls from Poperinge,

And their coming out in force;

And they work the whole year,

And they earn lots of money! |

Adeletje Deklerck making lace in the Bruges almshouse, August 1968. From Biekorf (1968)

The strongest concentration of lacemakers in Bruges lived in the parish of Saint Anne, but we have less information about Saint Anne’s Day celebrations there, suggesting that they may have been a fairly modern innovation. Most of what we know depends on the oral history interviews undertaken in the 1960s by the folklorist Magda Cafmeyer with old lacemakers resident in the city’s almshouses.[13] For instance Adeletje Deklerk explained that the young women in the lace school saved one or two centimes a week which they put together to pay for the wagon and cakes, but that for three weeks before they worked solidly on earning some drinking money. As at Poperinge it was a two-day holiday. On the second day there was a prize-giving ceremony in the school itself. But the main event was on the first day, when the the lacemakers took a horse-drawn charabanc trip to Gistel and the shrine of Saint Godelieve (the pious wife of an abusive and, finally, murderous husband – a story familiar in many forms to lacemakers). While on the way, they sang:

Wij zijn bijeen en we trekken naar Sint Annetje,

wij gaan op zoek al achter een ander mannetje,

wij zijn bijeen

en we zullen niet meer scheen,

wij zijn gezworen kameraden

en ze zien’ aan onze trein (bis)

dat we van Sint Anne zijn (bis) |

We’re all together and we’re off to Saint Anne’s

We’re looking out for another man,

We’re all together

And we’ll never part no more,

We’re sworn comrades

And they can see from our verve

That we’re from [the parish of] Saint Anne. |

The camaraderie of the lacemakers, their sense of collective identity, both local and occupational (which sometimes included, and sometimes excluded, the nuns who accompanied them on the trip) comes across strongly in these songs.

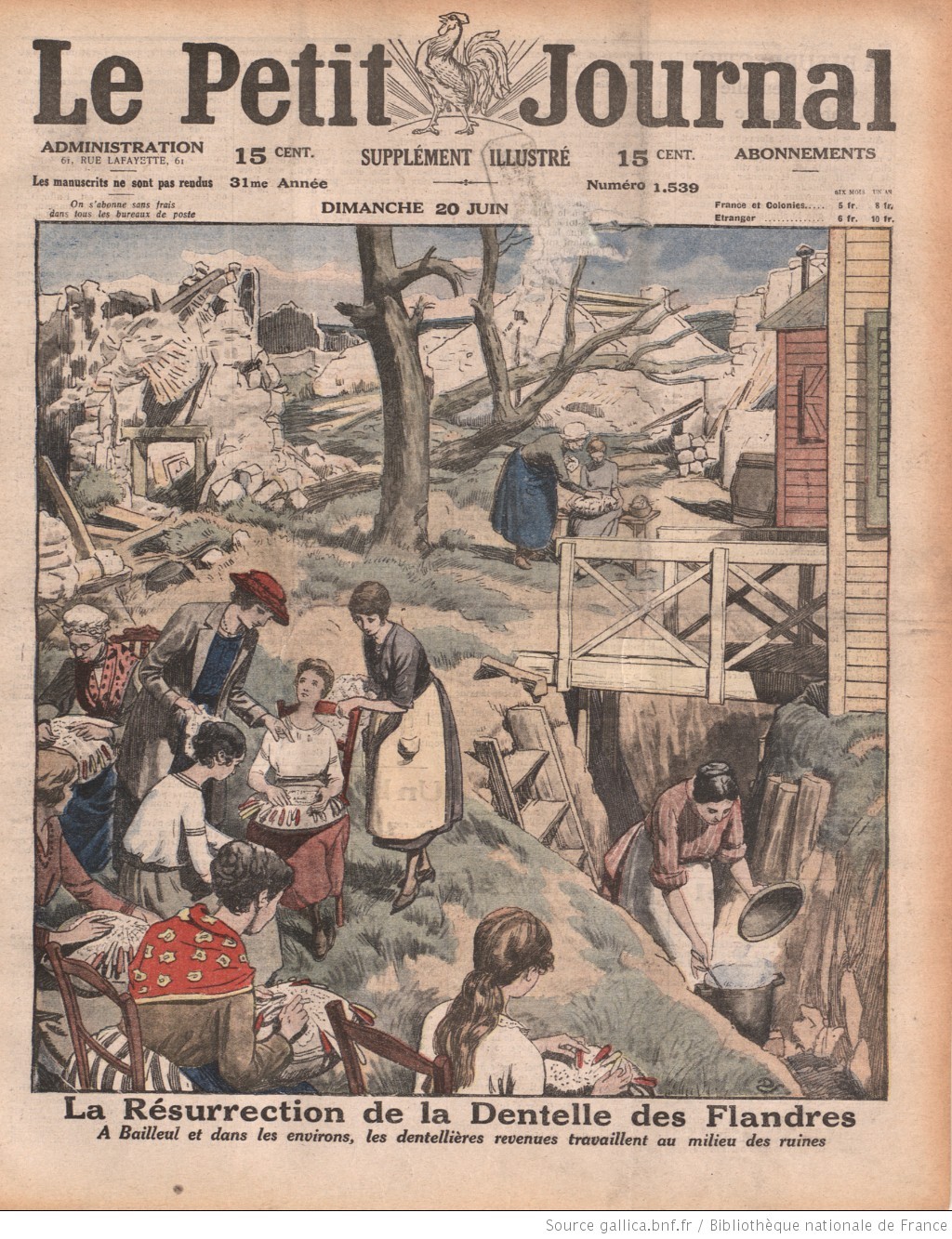

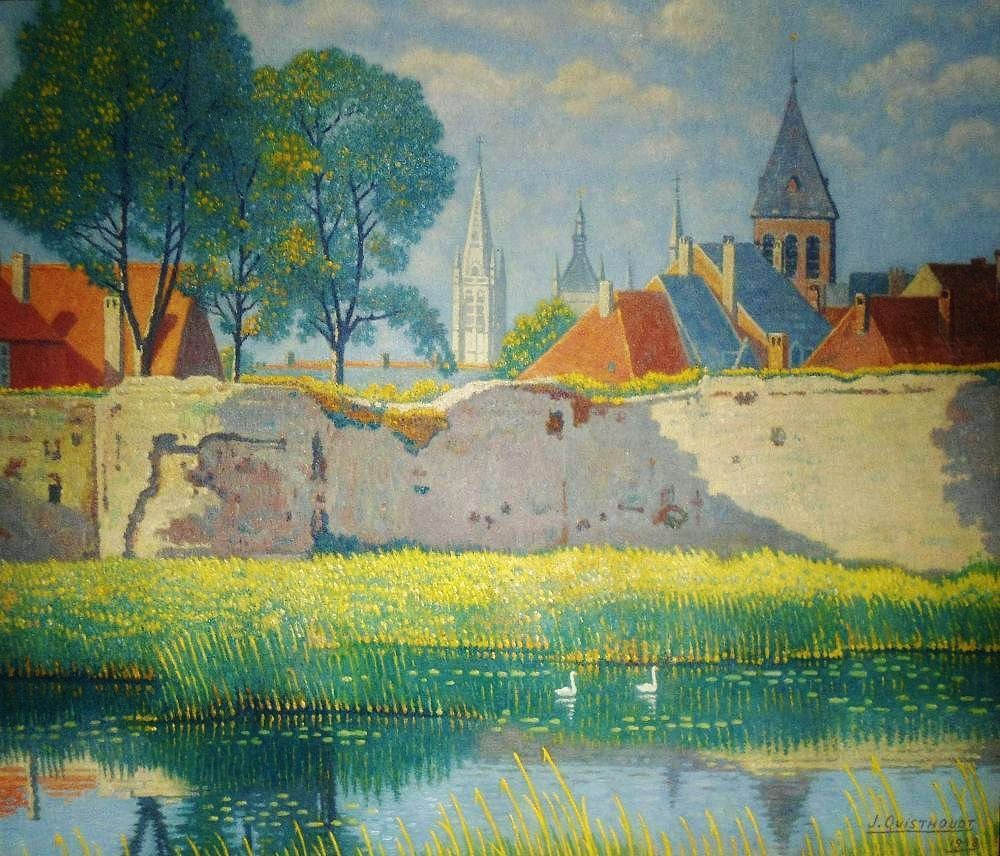

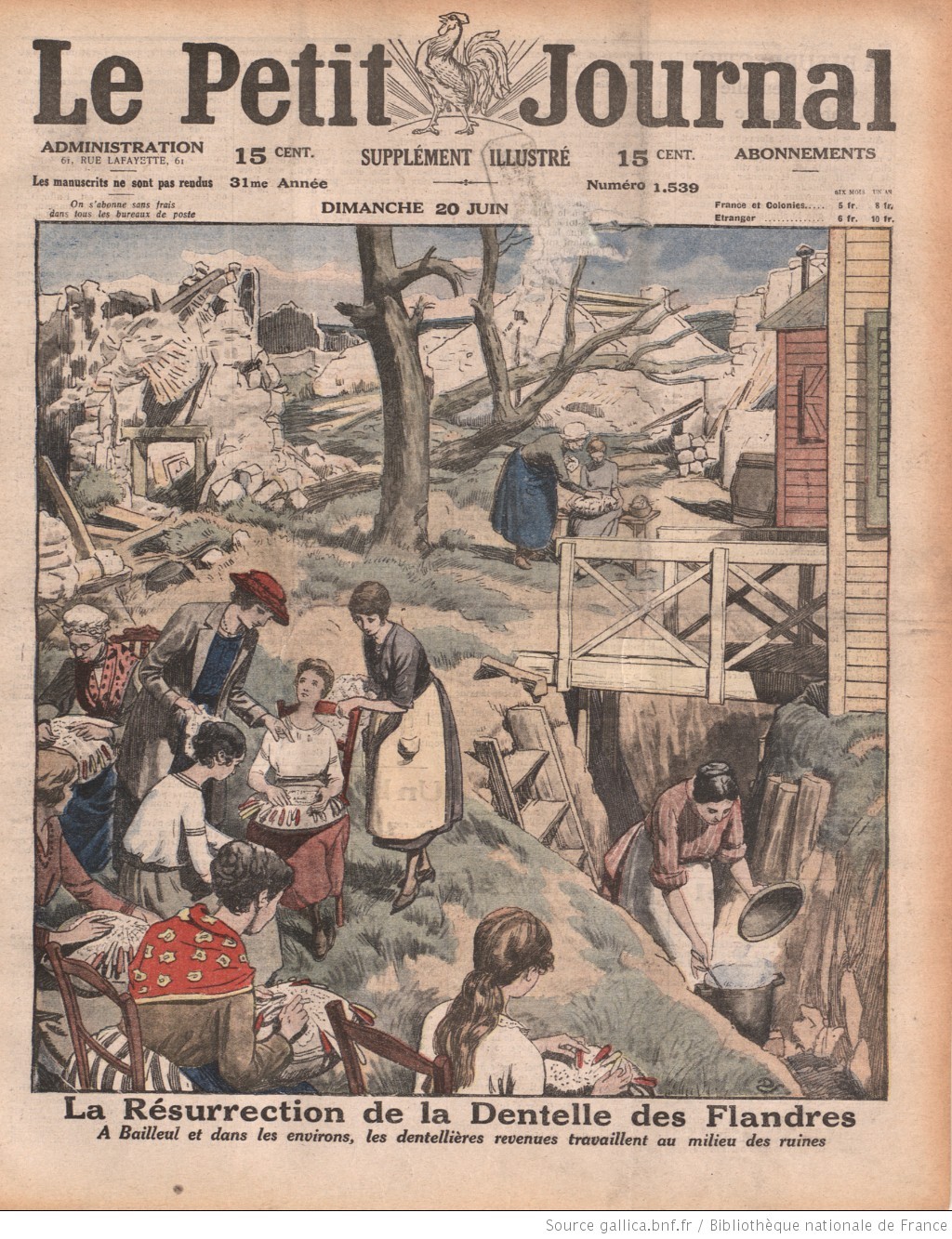

After the First World War there was a concerted attempt to revive lacemaking and its associated customs in Bailleul and the surrounding region. The town was almost totally destroyed during the Ludendorff Offensive in the spring of 1918 but when a visiting American philanthropist, Richard Nelson Cromwell, toured the region in 1919, he was moved by the sight of lacemakers working among the ruins. His support for the French charity ‘Retour au foyer’ (Back to the hearth) underwrote the establishment of lace schools in Bailleul and nearby Méteren and Saint-Jans-Cappel. The underlying philosophy was that the traditions and values interrupted by the war should be renewed, including a proper gender order. Lacemaking would enable women to contribute to the household budget without leaving their homes. The charity not only funded the schools but also undertook the sale of their produce in Lille and Paris.

Le Petit Journal, supplement illustré, no. 1539, 20 June 1920 : ‘La Résurrection de la Dentelle des Flandres’. From Gallica.

Part of this ‘return’ involved reviving Saint Anne’s Day celebrations. In 1921 the local organiser in Méteren, Marguerite de Swarte (1874-1948), wrote to the charity’s president Paul Dislère to explain how the children had passed the day.

On the day before, our young workers and brought in armlods of flowers with which they made garlands to decorate both the front and the interior of the school. A [lace-maker’s] chair, a pillow, a support and an aune [used to measure lace] were festooned with flowers, you would think it was a flower festival. In the evening, after work, the local lacemakers came to admire the charming school which reminded them of the holidays of yesteryear, they enjoyed themselves with the children and brought to mind the old Flemish songs… The following morning our children, and all the lacemakers of Méteren, went to mass in honour of Saint Anne, then they returned to the school, singing their old songs. There a meal of Flemish cakes and chocolate awaited them, which they enjoyed very much. Then a bus came to take them to Ypres… There they had a cold lunch of ham sandwiches, Flemish cake, pears and beer, and they walked among the ruins. At 3:00pm they went on to Poperinge, to visit the lace school, and with the fifty young lacemakers they shared more local specialities, bars of chocolate and beer. Then there were songs and round-dances in the school playground, until at 7:00pm the happy band climbed back aboard the bus to return to Méteren via Saint-Jans-Cappel.[14]

Marguerite de Swarte (1874-1948), patron of the lace revival in Méteren

Saint Anne celebrations continued throughout the interwar period, and there is even a picture of the crowning of the Méteren lace mistress, Hélène Loozen, in 1936, surrounded by the garlanded tools of the lacemaker’s trade.

Hélène Loozen, crowned lace mistress at Méteren, Saint Anne’s Day 1937. The lady with the pillow is Marie Delie, lace mistress of the school before the war and a well-known lacemaker.

[1] Ludo Steyn, Jan Frans Willems: Vader der Vlaamsche Beweging (Antwerp: De Bezige Bij, 2012).

[2] Jan-Frans Willems and Ferdinand Snellaert, Oude Vlaemsche Liederen ten deele met de melodieën (Ghent: F. and E. Gyselynck, 1848), nos. 256-7.

[3] Jan Bols (ed.) Brieven aan Jan-Frans Willems (Ghent: A. Siffer, 1909), p. 452.

[4] Stefaan Top, ‘Chants populaires des flamands de France (1856): A Contribution to Comparative Folksong Research, France/Belgium : Flanders’ in James Porter (ed.) Ballads and Boundaries: Narrative Singing in an Intercultural Context (Los Angeles: UCLA, 1995), pp. 315-24.

[5] Edmond de Coussemaker, Chants populaires des flamands de France (Ghent: F. and E. Gyselynck, 1856), xii-xiii.

[6] Coussemaker, Chants populaires, pp. 307-19.

[7] Arreté, Maire de la ville de Bailleul, 2 juillet 1858

[8] Stéphane Lembré, ‘Les écoles de dentellières en France et Belgique des années 1850 aux années 1930’, Histoire de l’éducation 123 (2009): 55.

[9] Michel Le Calvé, Souvenir de Bailleul (Dunkerque: Westhoek, 1983), pp. 40-1.

[10] Eugène Cortyl, ‘La dentelle à Bailleul’, Bulletin du Comité flamand de France (1903) : 231.

[11] For information on ‘zoete Mène’ see https://westhoekverbeeldt.be/ontdek/detail/8d838922-bbc5-11e3-a56d-875083d05b38

[12] Albert Blyau and Marcellus Tasseel, Iepersch Oud-Liedboek (Brussels: Commission royale du folklore, 1962), pp. 237-318 : ‘Het boek der Klein-Sacramentdagliedjes en Sint-Annaliedjes’. See, especially, no. 124 ‘Sint-Annadag’ and no. 125 ‘De Kinders van de Babbelaarsstrate’.

[13] Magda Cafmeyer, ‘Oude Brugse spellewerksters vertellen: Adeletje in ‘t Godshuis’, Biekorf 69 (1968): 364-5.

[14] The story of the lace revival in Méteren and Bailleul is well told on the Méteren village website: https://meteren.pagesperso-orange.fr/IV.1%20Dentelles-%20Accueil%20et%20presentation.htm as well as in the catalogue of the exhibition Bailleul en dentelles: Exposition, 27 juin-15 octobre 1992 (Bailleul: Musée Benoît de Puydt, 1992). Both quote the letter from Marguerite de Swarte.