In our last post about lacemakers ‘keeping cattern’ on 25 November, we said that Saint Catherine ‘was not usually the named patron of European lacemakers’. However, we have learnt that there was one exception: the lacemakers of Antwerp province in Belgium, and specifically Mechelen (Malines), celebrated Saint Catherine’s Eve.

We owe this information to the Flemish writer Herman Baccaert (1883-1921) who, together with Antoine Carlier de Lantsheere, compiled an Encyclopaedia of lace-related information. Sadly this manuscript was lost during the First World War, but Baccaert did publish a few articles on lacemakers’ traditions, including their feast-days. He also wrote a novel set among lacemakers, which we’ll return to in a future blog.

Herman Baccaert of Mechelin (1883-1921)

According to Baccaert, in most of Belgian and French Flanders, and in Brabant, the lacemakers’ patron was Saint Anne, mother of Mary, whose feast fell on 26 July. There were some exceptions and additions. In Ieper (Ypres) the lacemakers’ holiday was ‘mooimakersdag’, the Wednesday preceding ‘Klein Sacramentdag’, which fell on the Thursday following Corpus Christi. (As the date of Corpus Christi depended on Easter, this was a moveable feast.) In Geraardsbergen (Grammont) in southern Flanders, the lacemakers’ celebrated instead Saint Gregory the Great. (Originally the holiday fell on 12 March, which oddly is Saint Gregory’s feast-day in the Orthodox Church but not the Catholic Church. Then, in the nineteenth century, it was moved to 9 May. According to a local lacedealer interviewed by Baccaert, the explanation for this was that the weather was better in May. However, 9 May is the feast-day of Saint Gregory Nazianzen, a different saint; it is also the feast of the translation of Saint Nicholas, which was an important holiday for lacemakers in Lille. So there may have been more going on here.) Although Baccaert did not mention this, Saint Theresa of Avila’s feast on 15 October was also popular among lacemakers in West Flanders, in Bruges and Courtrai (Brugge and Kortrijk). But this holiday was promoted by some religious orders which held the saint in particular esteem; in general Saint Anne was the recognized patron in West Flanders.

In Antwerp province, however, it was Saint Catherine. It is worth quoting Baccaert’s description in full because it offers some interesting parallels with ‘catterning’ in the East Midlands. The lace industry had been in decline in the region for several decades, so Baccaert was referring to the past, not current practice.

“On Saint Catherine’s eve, at sunset on 24 November, ‘the candleblock was washed’ [‘den lichter begoten’]. The candleblock was a wooden stand which served as an appliance to spread light over the lacemakers’ pillows. It consisted of a candle or an oil-lamp as well as a spherical bottle filled with pure water, the so-called ‘ordinaal’, which concentrated the light falling on the pillow.

“In the evening they cooked up a brandy punch called ‘the Devil in Hell’, which was passed to and fro because there was always another willing mouth to take care of. It was the season for smoked herring and these were laid on the fire to sizzle and spit; everyone also had some tasty morsel, especially gingerbread and sweetmeats, and thus late into the night they would sing, gossip and tell stories.”

‘Washing the candleblock’ was also the euphemistic name for celebrating Catterns in parts of the East Midlands. Saint Catherine’s was ‘Candle Day’, because traditionally this was the day when lacemakers began to use artificial light. And just as there was a Cattern cake in the East Midlands, so there was a ‘Sint Catharinagebak’ in East Flanders: the recipe is given on p.99 of André Delcart’s Winterfeesten en Gebak: Mythen, folklore en tradities (Cyclus, 2007) This is not the only parallel in the customs of the two regions: the chanting of ‘tells’ in Midlands lace-schools echoes the use of ‘tellingen’ to control the pace of work in Flemish lace workshops. Here is another which also tends to confirm the claim ― often asserted but difficult to prove ― that lace skills came to England from the Low Countries with Flemish migrants in the sixteenth century.

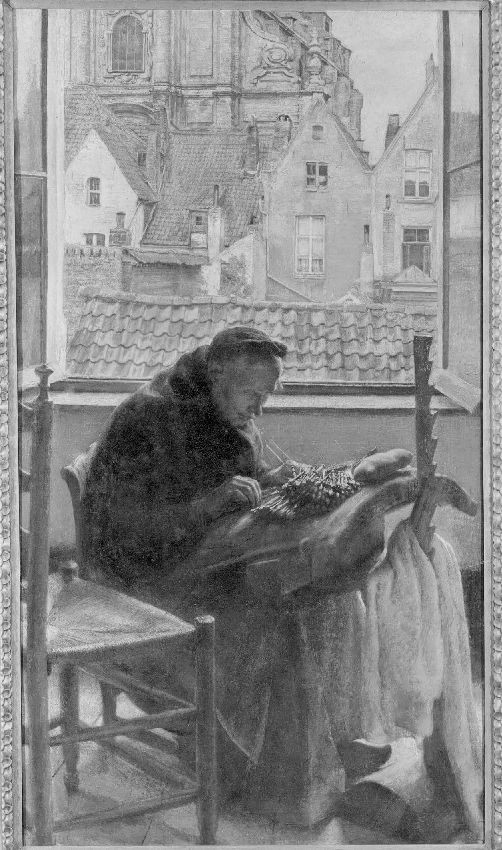

Alexander Struys, ‘The Lacemaker of Mechelen’, 1902

Further Reading

Baccaert, Herman. ‘Gebruiken bij Kantwerksters’, Volkskunde: Tijdschrift voor Nederlandsche Folklore 19 (1907-8): 223-229

Baccaert, Herman. ‘Bijdrage tot de Folklore van het kantwerk’, Volkskunde: Tijdschrift voor Nederlandsche Folklore 21 (1910): 169-175.

There is a very good Flemish website on Mechelen lace and lace history, ‘Mechelen & Kant‘.