Lancelot Théodore Turpin de Crissé, ‘Corpus Christi Procession leaving the Church of Saint-Germain, Paris’ (detail), 1830. From the website Schola Sainte Cécile. We have not found any paintings of Corpus Christi from nineteenth-century Ypres, but this gives an impression of the occasion.

Continuing in our series on lacemakers holidays we arrive at Corpus Christi, the celebration of the real presence of Jesus in the Eucharist, which is a moveable feast. This year (2020) it fell on Thursday 11 June, which means that this Thursday (18 June 2020) is the ‘octave’ of Corpus Christi, known as ‘lesser Corpus Christi’ or, in Flemish, ‘Kleinsacramentsdag’. The period between was, in the Catholic sense, a week of indulgence, but for Ypres lacemakers it was a week of indulgences. Kleinsacramentsdag was the lacemakers’ mass and feastday in this city, and in the mid nineteenth century they celebrated it enthusiastically. ‘I won’t describe it because I wouldn’t be believed’, wrote one local journalist.[1]

Pinot & Sagaire, imagists of Epinal, ‘Corpus Christi Procession’, mid nineteenth century. Note the array of lace on display.

When and why Kleinsacramentsdag became the lacemakers’ holiday we don’t know. The custom was limited to the city of Ypres (and perhaps Veurne[2]). In the early modern period Ypres was the seat of its own small bishopric (suppressed in 1801), and ecclesiastical authorities often shaped local festive calendars, but lacemakers in other towns within the diocese, such as Poperinge and Bailleul, followed the general West Flemish pattern of celebrating on Saint Anne’s day. Perhaps it was because Corpus Christi processions – when the clergy, accompanied by congregations, confraternities, the military and others, paraded the Holy Sacrament through the streets – were major occasions for the display and purchase of lace as vestments and church ornaments. But we know that the lacemakers’ celebration was already established in the eighteenth-century, because a local comic poet, Karel-Lodewijk Fournier, wrote to his niece, when she became a nun, to wish her a long life and that when she died she would be carried to heaven like the prophet Elijah in a ‘klein sacramentdagwagen’, the waggons lacemakers hired and decorated to carry them out to country inns to continue their partying.[3]

Louise De Hem, ‘After the Procession, Ypres’, 1892. Yper Museum

Despite this long history, it’s rather hard to find out much definitive information about the event itself. Ypres newspapers began to mention Kleinsacramentsdag in the 1860s but usually to document its decline. In 1867 the local paper De Toekomst reported that, while fifteen years earlier the ‘lacemakers’ mass day’ was generally celebrated, now only the children from the laceschools marked it: Kleinsacramentsdag was ‘dead… and buried’.[4] And yet local papers were still complaining about lacemakers’ excesses on the day well into the twentieth century.

Lacemakers of Ypres, postcard c. 1912

We do know that preparations might start some weeks before the day itself, as lace-schools, of which there were about forty in the city in the mid nineteenth century, began to learn the songs they wanted to perform. Local printers and streetsingers brought out new songs for the occasion.[5] There was a special repertoire of Kleinsacramentsdag songs which we will discuss below, but lacemakers also sang topical songs, commenting on local politics and personalities. Very few of these survive but we have already encountered one: the 1848 attack on French lace dealers and the Ypres prud’hommes. Another lamented the introduction of machine-made lace net in 1830, a major threat to the handmade lace industry.[6] It was still popular more than sixty years later:

| ‘t die wilt hooren in een lied, wat dat ‘t jaar dertig is ‘geschied: De kanten geen voor nieten, Hoe dan! Dat zoud’ een mensch verdrieten! En wuk dink je daarvan? |

Who wants to hear a song, About what happened in 1830: Lace goes for so little, How then! That would make a person grieve! And what do you think about that? |

| Wuk dink je van den Ingelschman? Hij brengt de tule al in ons land! En dat bij g’heele hoopen! Hoe dan! Ondamme ze zoûn koopen! En wuk dink je daarvan? |

What do you think of the Englishman? Who brings ‘tulle’ into our country! And that by whole shedloads! How then! So that they can be damn well bought! And what do you think about that? |

| Het is al tule lijk papier: ‘t deugt voorwaar ook niet een zier! ‘t Is goed voor twee, drij waschten, Hoe dan! Zijn dat geen mooie kosten! En wuk dink je daarvan? |

This tulle is like paper: It’s not worth anything! It’s good for just two or three washes, How then! That’s no bargain! And what do you think about that? |

The festivities really began on the Wednesday, which was termed ‘Mooimakersdag’. To make something ‘mooi’ means to clean and decorate it, and in theory the afternoon before any feast could be a ‘mooimakersdag’, but the term is strongly associated with Ypres and lacemakers.[7] Lacemakers’ homes were thoroughly scrubbed and the lace schools adorned with bouquets of flowers, ribbons and necklaces of blown egg-shells (this detail reappears frequently and so we assume it had some importance, though quite what we don’t know). In the evening parties of lacemakers could be seen wandering through the streets, some in male attire, others in disguise, singing and dancing together. Mocked up mannekins of lacemakers sitting at their pillows appeared at street corners, to which passersby would tip a penny.

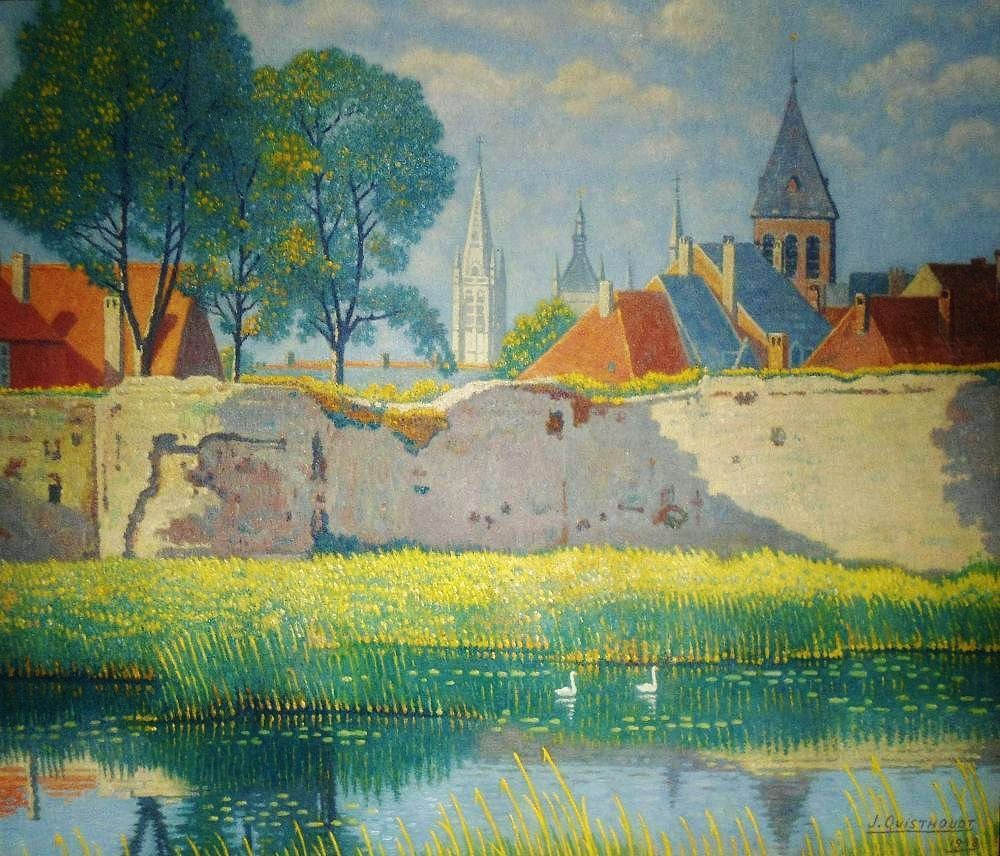

Jozef Quisthoudt, Ypres ramparts by the Lille Gate, and the Sint-Pieterskerk beyond, 1949. Yper Museum

The following day, the apprentice lacemakers were led through the streets singing to mass in the church of St Peter. Thereafter the festivities spread out again into the streets. The children played Flemish bowls, with the winners being named ‘queens’ for the day. Lace schools and other groups mounted their decorated waggons with picnics for trips to country inns. Some, presumably the more religiously minded, went to the Church of Voormezele to see the Holy Blood of Christ. In the evening lacemakers continued to sing and dance in pubs such as Den Hert, Het Smisken and Den Zoeten Inval, and the streets resonated with bawdy songs, and lewd behaviour, outraging local newspapers who pointed officials to a new 1905 law (‘loi Woeste’) which imposed major fines and imprisonment for offences against public morality.[8] All these scenes were repeated the following Monday which was likewise termed ‘Mooimakersdag’.[9]

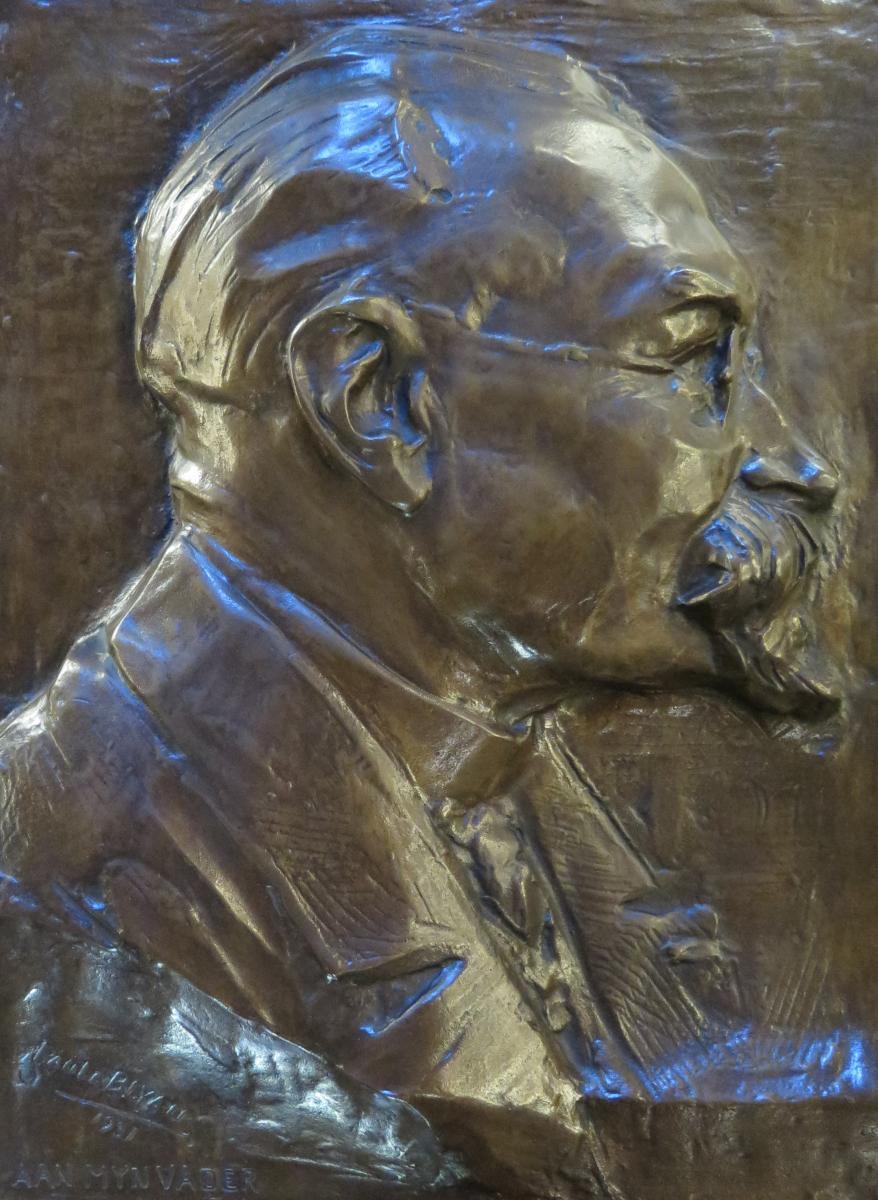

Paula Blyau, Portrait of Albert Blyau, her father, Yper Museum

The spirit of the celebrations are well encapsulated in the ‘kleinsacramentsdagliedjes’ that Ypres lacemakers sang. Nearly forty of these were noted by the local teacher Albert Blyau, with the help of the musician Marcel Tasseel, in lace schools and from lacemakers in the 1890s. We’ve translated a few items in this repertoire below. Some of these were general festive or drinking songs, others were part of a specific repertoire of lacemakers’ feastday songs. Many proclaimed the medicinal virtues of a ‘fresh young lad’, while a few took aim at clerical figures and ‘kwezels’ (religious bigots, or specifically beguines). A substantial proportion were soldiers’ songs – in folklore soldiers were ‘devil-may-care’ types who enjoyed a life of little work and many liberties; hence on the few days lacemakers’ had leisure to enjoy they took on the character of soldiers. Not many of these songs were so blatantly obscene that one could foresee them falling foul of the loi Woeste, but according to Blyau some were accompanied by gestures which made their meaning very plain.

This first song, which has been recorded by the Belgian folk group Sidus, sets the tone:

| Wij hebben ons kusje in ‘t kasjen gesteken, Boutjes en spellen en g’heel de boetiek. We’n zullen dees’ week van geen werken meer spreken: Boeravezeeve is onze muziek! Tralala, lafaderalier’! Tralalalia, lafad’rala! |

We’ve thrown our pillow into the shed, Bobbins and pins and the whole caboodle. This week we shan’t talk about work any more: The tambourine is our music! |

| Wij hebben ons mutsje doen optooien, Ons kapje naar de mode gezet; Wij dragen ons kleedje van voren in plooitjes, Wij zullen dansen proper en net! Tralala, etc. |

We’ve decked out our bonnets, Our hats are the height of fashion; We wear our dresses with pleats at the front, We shall dance neat and proper! |

| En als mijn moeder zal komen vragen: Dochter, en doen je voetjes geen zeer? Wel, moeder, zou ik durven klagen? Morgen dans ik nog vele meer ! Tralala, etc. |

And if my mother comes and asks: Daughter, don’t your feet hurt? Well mother, can I complain? Tomorrow I’ll dance a whole lot more! |

This was a popular song among Ypres lacemakers, though was also associated with other lacemakers’ feastdays.[10] In another song the tools of the lace trade were not just put away, the ‘boutjes’ or bobbins were deliberately broken.[11] Kleinsacramentsdag was really a revolt against work, and those who imposed work discipline. Hence in another a magistrate asks a lacemaker if she’ll take a young man to be her husband, on condition he punches the lace mistress.[12]

As well as dancing lacemakers embraced food, drink and love. Some of these songs were variants of widely sung tunes, such as ‘Zoete lieve Gerritje’:

‘’t Is Spellewerkersmesdag,

Zoete lieve Gerritje!’

‘t Is Spellewerkersmesdag,

Zoete lieve Mei !

The song continues that ‘these are the days of pleasure’, which the lacemakers will celebrate fully. They will eat sausages and potatoes, drink sugared brandy, and make the first peasant who comes along pay for it all.[13]

Cross-dressing, one element in lacemakers’ celebrations (and which is mentioned in accounts of Catterns and Tanders in the English Midlands), was also a theme in their songs. In one a young woman dresses as a sailor to follow her lover, the ship’s captain. Her sex in revealed when she falls from the rigging in a storm. By the time the ship returns to port, she is nursing a little baby sailor.[14]

Although freely spending money was essential to the spirit of this feast, the lacemakers did not forget that they were numbered among the poor. This reworking of a French dance tune is one of the very few lacemakers’ songs for which we have an audio record, thanks to the Belgian radio presenter Pol Heyns, who recorded from Ypres schoolgirls in January 1939.

| Klein-Sakermentdag die komt aan, Vivo lajon ! En me gaan al met den char-à-bancs. Van vivolee en marionnee ! Siliadono ! vivo lajon ! Berlabono ! Vivo lajon ! |

Kleinsacramentsdag is here, Vivo lajon! And I’m ready to go on the waggons. Van etc |

| De rijken gaan naar buiten, En den arme gaat om stuiten. Van vivolee, etc. |

The rich go out [enjoying themselves]

And the poor bounce along. Van etc! |

| De rijken dragen krullen, En den arme draagt palullen. |

The rich wear curls And the poor wear rags |

| Den rijke draagt gelapte schoên, En den arme-n en zou ‘t niet durven doen. |

The rich wear fixed up shoes Which the poor wouldn’t dare to do. |

| Den rijke zit up ‘t hooge lood, En den arme met z’n billen bloot. |

The rich are in the top positions And the poor with their bare buttocks. |

| Moeder, den rijke-n en kies ik niet, En den arme-n is m’n zoetelief! |

Mother, I don’t choose the rich man, The poor man is my sweetheart! |

But all good things must come to an end: the celebrations closed and the lacemakers had to return to the lace school, not without one final complaint.[15]

| Klein-Sacramentdag is deure: Uus geldetje ben ik kwijt: Nu zit ik hier en treuren Met kleinen appetijt |

Kleinsacramentsdag is expensive: I’ve spent all my money: Now I sit here and cry With little appetite. |

| De boutjes aan de galge! Het kusje aan ‘t perlorijn! ‘k Wenschte dat het alle dage Klein-Sacramentdag mochte zijn! |

The bobbins to the gallows! The pillow to the pillory! I wish that every day Could be Kleinsacramentsdag! |

| De schoolvrouw kwam vragen ‘Wat, duivel ! heije in je zin? E perkamentje in acht dagen, Is dat geen groot gewin?’ |

The lace mistress came and asked ‘What, Devil ! Are you in your senses? A pattern in eight days, Is that not rich reward? |

Ypres, lacemakers in the rue de Lille

[1] De Toekomst, 25 June 1870 ‘Stads Nieuws’.

[2] We have found a single mention that it was also the ‘spellewerkersmesdag’ in Veurne: Rond den Heerd, 4:26 (1869): 206.

[3] Karel-Lodewyk Fournier, Naergelaetene tooneelstukken en rymwerken (Ypres: Annoy-Vandevyver, 1821), Vol. 5, p. 354.

[4] De Toekomst, 30 June 1867 ‘Stads Nieuws’.

[5] Apparently the local printer Dedeyne produced a specific collection of ‘spellewerkliedjes’, but we have not been able to track down a copy.

[6] Albert Blyau and Marcellus Tasseel, Iepersch Oud-Liedboek (Brussels: Commission royale du folklore, 1962), no. 120, ‘Kantwerksters Leed’.

[7] Leonard Lodewijk De Bo, Westvlaamsch Idioticon (Bruges: Edw. Gailliard, 1873), vol. 1, p. 711.

[8] ‘t Nieuwsblad van Yper en Ommelands, ‘Oneerbaarheden’, 15 June 1907, p. 1; Journal d’Ypres, ‘Une publicité efficace’,24 June 1911, p. 2.

[9] The two main sources for this summary are: De Toekomst, ‘Het speldewerk en Klein Sacramentdag te Ijperen’, 26 June 1871; and C.M. and L.D.W. [Maurits Cocle and Lodwijk De Wolf], ‘Ypersche Blijdagwijzer’, Biekorf 35 (1929): 273-8.

[10] Blyau and Tasseel, Iepersch Oud-Liedboek, no. 87; M.C. [Magda Cafmeyer], ‘Spellewerk te Ieper’, Biekorf 56 (1955): 332.

[11] Blyau and Tasseel, Iepersch Oud-Liedboek, no. 92.

[12] Blyau and Tasseel, Iepersch Oud-Liedboek, no. 95.

[13] Blyau and Tasseel, Iepersch Oud-Liedboek, no. 88; De Wolf and Cocle, ‘Ypersche Blijdagwijzer’: 278.

[14] Blyau and Tasseel, Iepersch Oud-Liedboek, no. 111. This song was very popular in nineteenth and twentieth century Holland and Belgium.

[15] Blyau and Tasseel, Iepersch Oud-Liedboek, no. 123. Variants of this song was also sung after other lacemakers’ feastdays. The line ‘my pillow to the gallows and my bobbins to the pillory!’ featured on a Ypres postcard in the early twentieth century: Johan Ballegeer and Jean-Pierre Braems, Vlas, Kant en Spellewerksters in oude prentkaarten (Zaltbommel: Europese Bibliotheek, 1981), no. 34.