As far as we know, Caroline Barnard’s The Prize: or The Lace-Makers of Missenden (1817) is the only substantial work of British fiction that is set entirely among lacemakers.[1]

The novels of Caroline Barnard (possibly a pseudonym) were part of a wave of improving literature which swept through British culture at the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth centuries. Many of the writers were associated with the revivalist Evangelical movement in the Church of England, and many were women. The most famous name associated with this literature is Hannah More (1745-1833), whose prodigious output of “Cheap Repository” tracts taught “the poor in rhetoric of most ingenious homeliness to rely upon the virtues of content, sobriety, humility, industry, reverence for the British Constitution, hatred of the French, trust in God and in the kindness of the gentry” (as the 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica put it).

Barnard’s rather smaller canon was similar in tone and, like More’s, was in part aimed at a juvenile market. The title of her first book was The Parent’s Offering (1813, and labelled as “Intended as a companion to Miss Edgeworth’s Parent’s assistant”, a reference to Maria Edgeworth, another female novelist, moralist and educationalist). Her Lace-makers of Missenden was recommended as suitable for ten to sixteen year olds by another exemplar and champion of female education, Elizabeth Lachlan (née Appleton, c. 1790-1849): “A very engaging work, and worthy of being placed in the child or youth’s library, with his best authors. Nothing of the kind can be more interesting than the progress of this beautiful, simple story, and the moral is perfect, as the conclusion is satisfactory.”

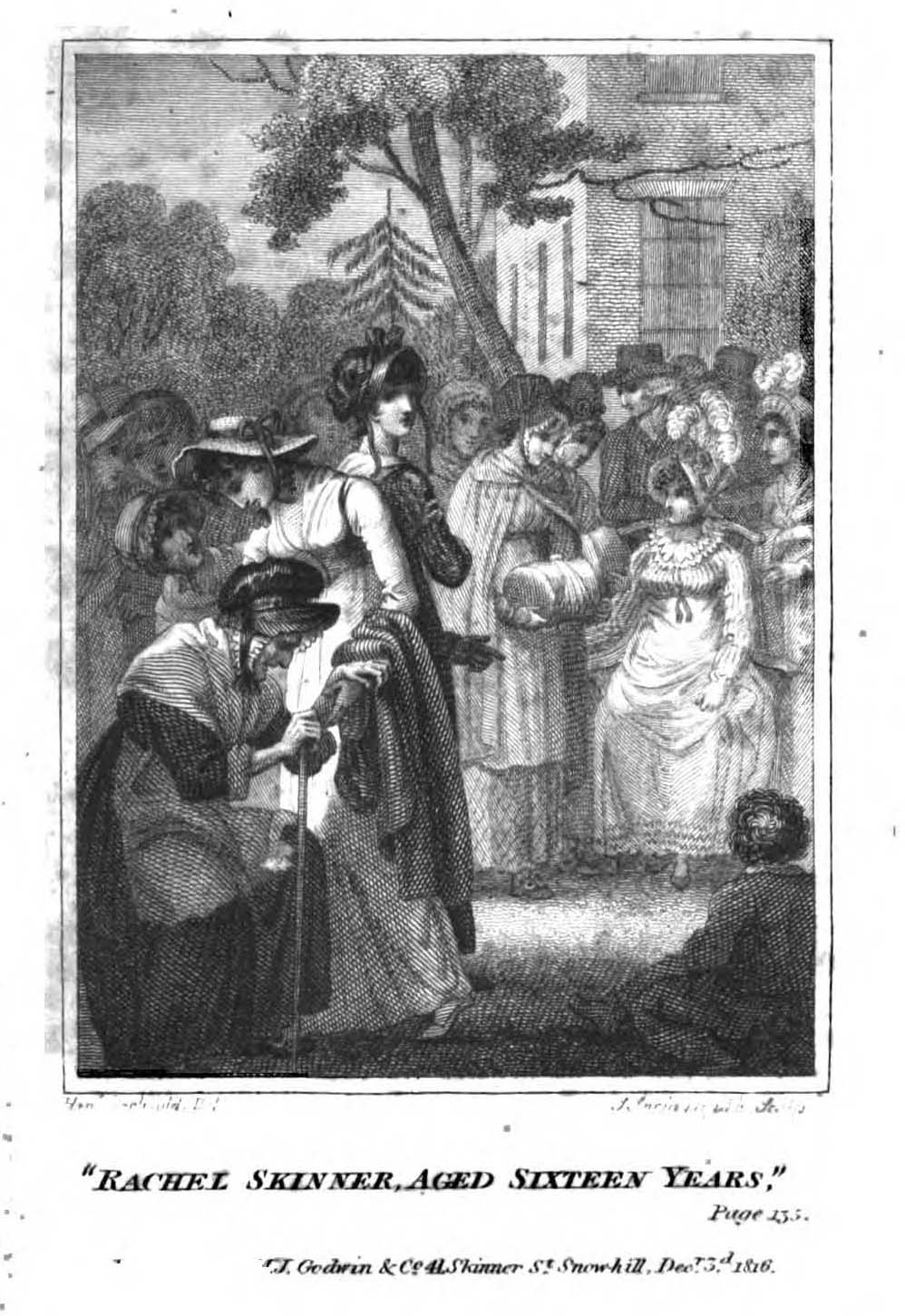

The frontispiece to Barnard’s The Prize depicts the prize-giving ceremony, and the moment when it appears that Rose’s rival Rachel Skinner will carry off the prize for the best lace

Like Hannah More’s famous The Shepherd of Salisbury Plain (1795), Barnard’s stories were often set among the rural working class. The poor could give moral lessons to the rich because, as the Reverend Legh Richmond, another of these Evangelical writers, explained, “Among such, the sincerity and simplicity of the Christian character appear unencumbered by those obstacles to spirituality of mind and conversation which too often prove a great hindrance to those who live in the higher ranks.” However such books were also intended as a means of controlling the growing numbers of literate labourers. With the radicalism of the 1790s still very much in mind, and aware of growing labour unrest again at the end of the Napoleonic Wars, middle and upper class commentators were concerned that the fabric of the social order was fraying. They feared revolution, and were attempting to inoculate the population with Christian morality. The message of Barnard’s The Prize – that one should not aspire above one’s station, and one should avoid new-fangled ideas coming from the cities – chimed exactly with this generally conservative political outlook.

Given these characteristics it is perhaps surprising that Mary Shelley (née Godwin) – daughter of Mary Wollstonecraft, wife of the radical poet Percy Bysshe Shelley and author of Frankestein – has been put forward as the real author lurking behind the pseudonym “Mrs Caroline Barnard”. The identification is most forcibly articulated by Emily Sunstein, and other Shelley scholars have proved sceptical. It is true that Barnard was published by Mary’s father, William Godwin; it is also true that the Shelleys moved to Marlow (Buckinghamshire), not too far from Missenden, in 1816, and while there took an interest in the lives of the local lacemakers. Mary wrote later, “Marlow was inhabited (I hope it is altered now) by a very poor population. The women are lacemakers, and lose their health by sedentary labour, for which they were very ill paid… The changes produced by peace following a long war, and a bad harvest, brought with them the most heart-rending evils to the poor. Shelley afforded what alleviation he could.” Admittedly the case for identifying Mary Shelley as Caroline Barnard is circumstantial at best, but it is intriguing to find in the diary of her step-sister, Claire Claremont, that when the Shelley ménage was at Bagni di Pisa, on 19 August 1820, she was reading The Parent’s Offering.

Although its characters exist largely to illustrate moral lessons, The Prize is quite a lively read, and demonstrates some knowledge of the lace business. The protagonists are Rose Fielding, fifteen, and her younger sister Sally, who have to support their invalid and widowed mother and their grandmother through their lacemaking. The grandmother had, in her youth, won a prize for lace, “the finest bit of lace that has ever been made in all Buckinghamshire!” as she never fails to remind her granddaughters. The prize was awarded by Lady Bloomfield whose patronage encouraged the lace industry, but “my lady Bloomfield is dead, and times are altered now, and girls are growing idle and good for nothing.” Grandmother’s grumbles are directed less at Rose, who is utterly dutiful and conscientious, than at Sally, who though she promises to make a yard of edging a day (at two shillings a yard), is constantly distracted, her lace gets dusty and her bobbins tangled.

The main source of distraction is the unkempt, gossipy and superstitious shopkeeper Mrs Rogers, and her niece Eliza Burrows, recently arrived from “Lonnon” to set up a millinery business in the village shop, now advertising the “newest fashion, from the most elegantest varehouse in all Lonnon”. Eliza quite turns Sally’s head with her “Wellington hat” and “Spanish cloak”, “epaulets” and “hussar sleeves” (fashions brought back with the victorious army from the Peninsula), and the promise that “you was intended to be genteel”. In vain does Rose warn her sister that “you are not a lady, nor ever will be, and that therefore you need not try to look like one”.

Also recently arrived in the village is the new squire, Sir Clement Rushford and his bride. Unlike their immediate predecessors – respectively a miser and wastrel – the Rushfords interest themselves in the life of the village. Lady Rushford and her niece Letitia Lenox take Rose Fielding under their wing. Inspired by the stories of Granny Fielding, the Rushfords re-establish not only the lace school in the village, but the lace Prize. But if the lace produced on her pillow had not reached the regulation length by Prize Day, the girl’s name would be struck off the school list. Rose, “a main good hand at her pillow” is presumed the most likely winner, though she has a rival in the form of sulky Rachel Skinner. But Rose is distracted both by teaching a neighbouring pauper child to read and by having to finish her sister’s lace as well as her own (for despite Sally’s claim that “I have never yet looked off my work from the time I have begun of a day”, her length is only half done). Come the moment of truth, the judges – not the gentry but local expert lacemakers – acknowledge Rose’s skill but report her lace fell short by two or three yards (consternation all round and hysterics from Granny). However, it turns out that wicked Eliza had stolen four yards of Rose’s lace to trim a “Regency ‘elmet” she intended to wear to a “melo-drame” performed by the officers of the 58th regiment garrisoned at Amersham. All is discovered, Eliza is dispatched back to London as “not fit for the country”, and Rose receives the Prize, “A SILVER TIME-PIECE”, engraved with Lady Rushford’s name. And to cap it all, Letitia’s father, Dr Lenox, announces he can cure widow Fielding of her lameness.

The moral of this story almost matches every characteristic of More’s tracts, including the “the kindness of the gentry”. However, Barnard is careful to show that there are irresponsible gentry just as there are undeserving cases among the poor. The Rushfords renew a social contract that had been unfulfilled for two generations. Lace, it appears, has always been an appropriate target for aristocratic benevolence. When, much later in the nineteenth century, the lace associations were founded by leisured, titled ladies to preserve the virtues of domestic industry, they were reviving a tradition of philanthropy, not inventing it. One wonders what they might have been reading in their formative years.

Barnard’s The Prize: or the Lacemakers of Missenden is freely available to read thanks to Google Books.

[1] This was our first post, back in 2015. We could now point to several!