In the journal Notes and Queries for 22 August 1868 there appeared the following request from the Shakespearean scholar Sidney Beisly (author of Shakespere’s Garden, among other things):

“The song we had last night.

Mark it, Cesario, it is old and plain:

The spinsters and the knitters in the sun,

And the free maids, that weave their thread with bones,

Do use to chant it.”

Twelfth Night, Act II, Sc. 4.

I should like to know if any of the songs which the lacemakers of times past sung are in existence, and where they are to be found. Am I right in believing that the free maids, noticed by Shakespeare in the above passage, were lacemakers? Any information on this subject will oblige

Over the next few months we intend to do our best to belatedly satisfy his interest, but we’ll start with the articles in Notes and Queries which prompted and responded to Beisly’s letter. In its nineteenth-century heyday, Notes and Queries was a meeting point for antiquarians, literacy scholars and budding folklorists. In fact the term folk-lore was coined in 1846 by the journal’s founding editor, William Thoms. In 1868, folksong collecting was not an established field of endeavour in England, unlike Scotland. The first English folk-song revival would have to wait for the turn of the century. But there were a few Victorian enthusiasts connected by journals like Notes & Queries, and of course the Shakespearean reference helped, for it provided folk-songs with their letter of literary nobility. Who could dismiss what the bard himself had deigned to notice?

There are two elements of Shakespeare’s depiction that are borne out by these nineteenth-century correspondents. Firstly, lacemakers had an established taste for old songs, even at the beginning of the seventeenth century when the trade was relatively new in England. Secondly, they had a penchant for the tragic and ghoulish, for the song the Feste sings in response to Duke Orsino’s injunction, starts:

Come away, come away, death,

And in sad cypress let me be laid….

We would hazard that the clown’s song may be part of a longer narrative ballad, but if so we have not been able to discover which one. However, it was just such ballads — narrative in structure, presumed old in date, heart-rending in content — that excited the interest of nineteenth-century song collectors.

Most of the information on lacemakers’ songs in Notes and Queries precedes Beisly’s intervention. In the edition of 4 July 1868 ‘J.L.C’ of Hanley Staffordshire inserted the following note (We have not been able to identify J.L.C., presumably he was not the genealogist Joseph Lemanuel Chester, a regular contributor under these initials, as he grew up in America):

A LACEMAKER’S SONG. — When I was a child, rising six years, my Northamptonshire nurse used to sing the following ditty to me as she rattled her bobbins over her lace-pillow:

“It rains, it rains in merry Scotland;

It rains both great and small,

And all the schoolboys in merry Scotland

Must needs to play at ball.

They tost their balls so high, so high,

They tost their balls so high,

The tost them over the Jews’ castel,

The Jews they lay so low.

The Jews came up to Storling Green:

‘Come hither, come hither, you young sireen,

And fetch your ball again.’

‘I will not come, and I dare not come

Without my schoolfellows all,

For fear I should meet my mother by the way,

And cause my blood to fall.’

She showed him an apple as green as grass,

She gave him a sugar-plum sweet;

She laid him on the dresser board,

And stuck him like a sheep.

‘A Bible at my head, my mother,

A Testament at my feet;

And every corner you get at

My spirit you shall meet.’”

This is a version of the Ballad of ‘Sir Hugh’, or ‘The Jew’s Daughter’ (Child 155, Roud 73, for the folk-song aficionados), an example of the anti-Semitic accusation of ritual murder which, it appears, originated in medieval England before spreading to Europe and beyond with horrific consequences, unfortunately not altogether relegated to the past. But for the moment we will concern ourselves only with the ballad, which tends to emphasise the murder rather than the ritual part of the story, at least as it was sung by lacemakers.

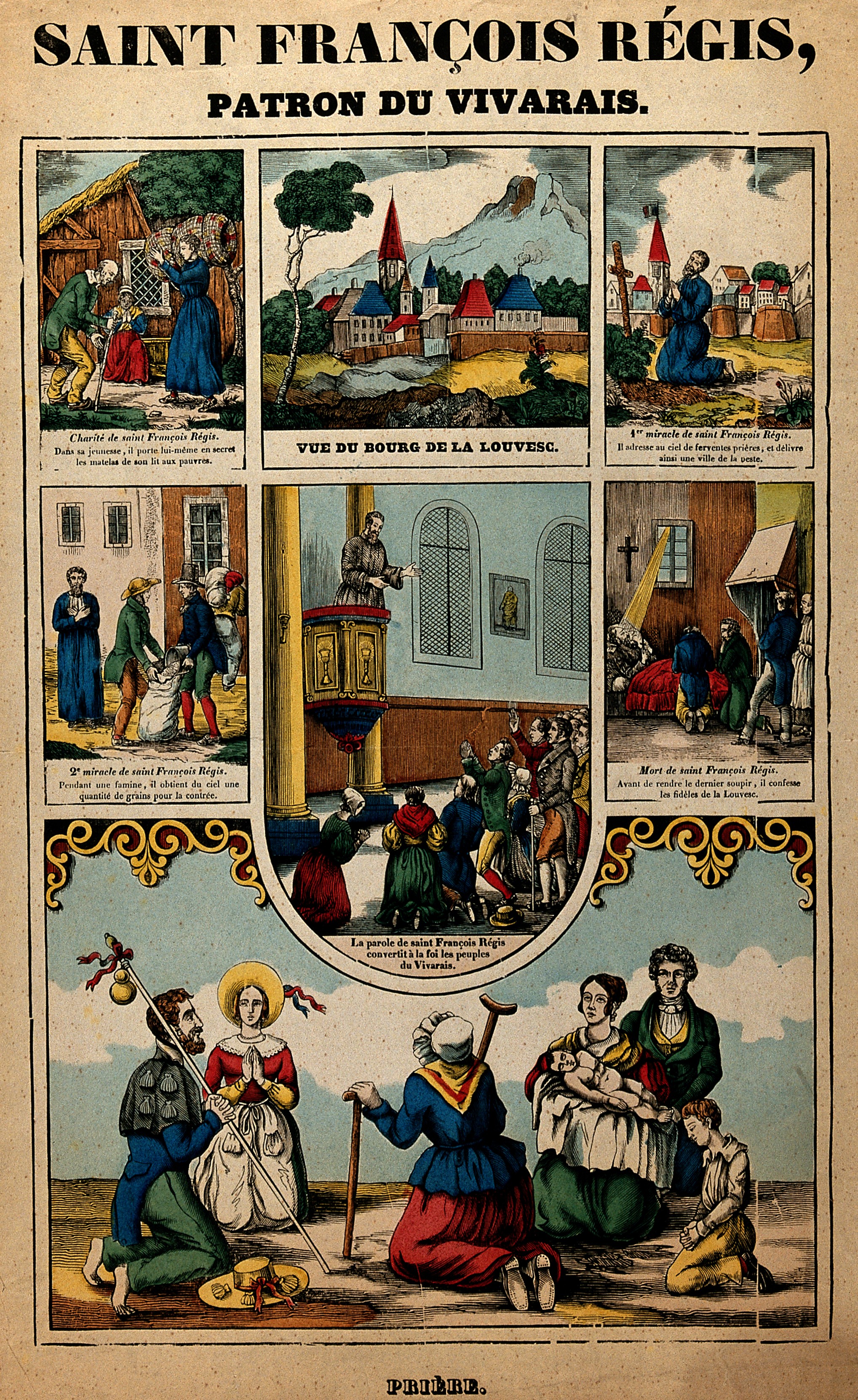

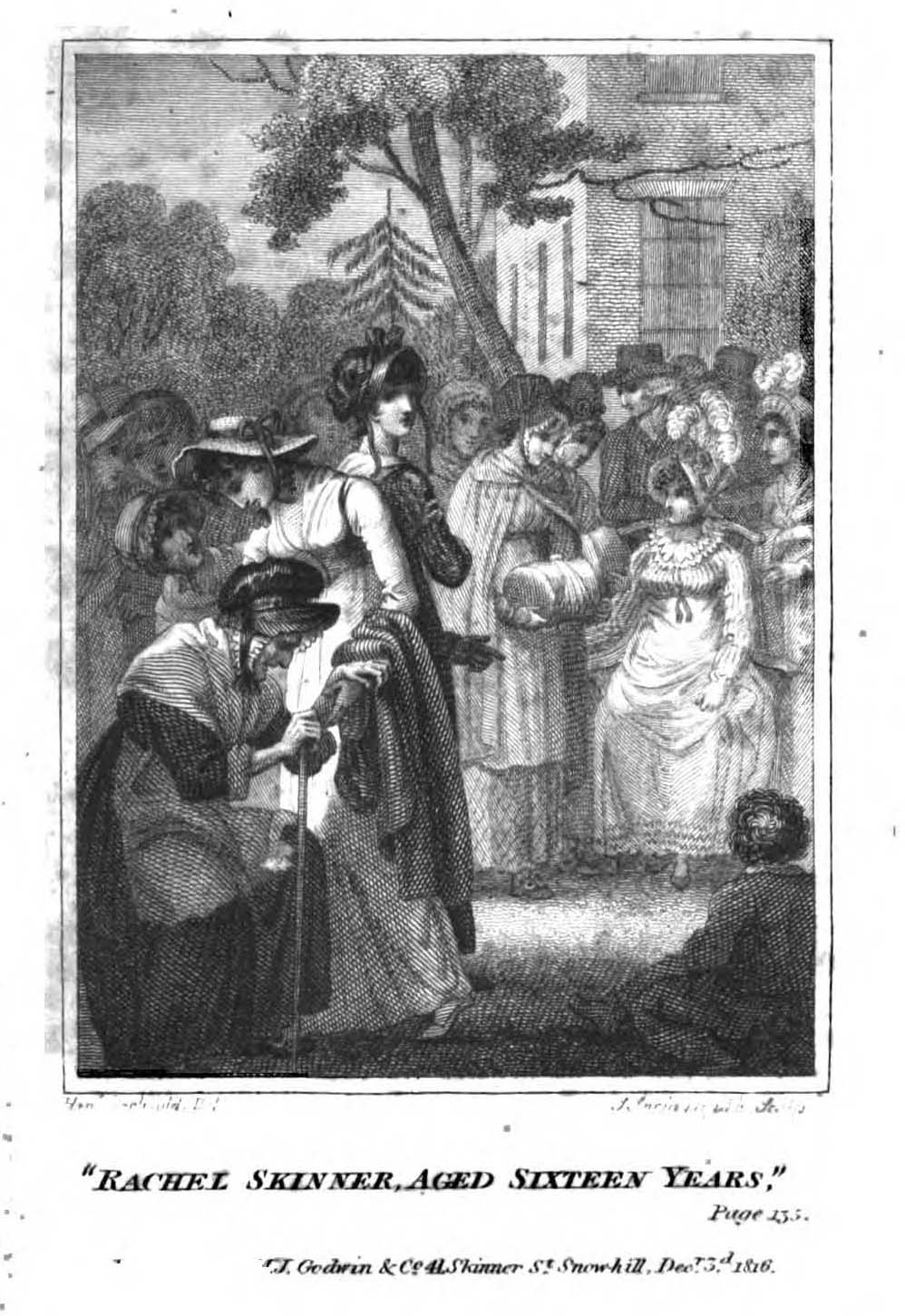

Thomas Percy’s 1765 Reliques of Ancient English Poetry, is the earliest source for the ballad ‘Sir Hugh’ (from Wikipedia Commons).

Lacemakers plural, because J.L.C.’s was not the first version of ‘The Ballad of Sir Hugh’ to appear in Notes and Queries. In the edition of 15 October 1853, C. Clifton Barry had asked “Why does not some one write a Minstrelsy of the Midland Counties”, before observing that the material was just as rich, and oddly akin to the ballads of Scotland (which were far better known even south of the border, thanks to the publishing endeavours of Walter Scott, James Hogg, William Motherwell, David Herd, Peter Buchan and many others). This Scottish tincture he had noticed in Gloucestershire and Warwickshire in versions of the drunken cuckold song ‘Our Goodman’ (Child 274, Roud 144) and the infanticide ballad ‘The Cruel Mother’ (Child 20, Roud 9). In response ‘B.H.C.’ (almost certainly Benjamin Harris Cowper, a biblical scholar, born in Wellingborough in 1822) wrote in on 24 December 1853 with the following:

THE BALLAD OF SIR HUGH, ETC.

The fact mentioned by your correspondent C. CLIFTON BARRY, at p. 357., as to the affinity of Midland songs and ballads to those of Scotland, I have often observed, and among the striking instances of it which could be adduced, the following may be named, as well known in Northamptonshire:

“It rains, it rains, in merry Scotland;

It rains both great and small;

And all the schoolfellows in merry Scotland

Must needs go and play at ball.

“They tossed the ball so high, so high,

And yet it came down so low;

They tossed it over the old Jew’s gates,

And broke the old Jew’s window.

“The old Jew’s daughter she came out;

Was clothed all in green;

‘Come hither, come hither, thou young Sir Hugh,

And fetch your ball again.’

“‘I dare not come, I dare not come,

Unless my schoolfellows come all;

And I shall be flogged when I get home,

For losing of my ball.’

“She ‘ticed him with an apple so red,

And likewise with a fig:

She laid him on the dresser board,

And sticked him like a pig.

“The thickest of blood did first come out,

The second came out so thin;

The third that came was his dear heart’s blood,

Where all his life lay in.”

I write this from memory: it is but a fragment of the whole, which I think is printed, with variations, in Percy’s Reliques. It is also worthy of remark, that there is a resemblance also between the words which occur in provincialisms in the same district, and some of those which are used in Scotland; e.g. whemble or whommel (sometimes not aspirated, and pronounced wemble), to turn upside down, as a dish. This word is Scotch, although they do not pronounce the b any more than in Campbell, which sounds very much like Camel.

Remains of the tomb of ‘Little Saint Hugh’ at Lincoln Cathedral (from Wikipedia Commons).

Cowper does not say that the singer was a lacemaker, but we can probably infer this from his later contributions to Notes and Queries. For example, on 22 December 1855, he returned to this ballad:

THE BALLAD OF SIR HUGH.

In Vol. viii., p. 614., six verses of this ballad will be found contributed by myself. In replay to inquiries since made, I have received six verses and a half additional. I copy these from the original MS. of “an old lacemaker, who obliged me with these lines,” as my informant says. I have corrected errors of orthography and arrangement. For the sake of the variations I copy the whole.

“It rains, it rains, in merry Scotland,

Both little, great and small;

And all the schoolfellows in merry Scotland

Must needs go and play at ball.

“They tossed the ball so high, so high,

With that it came down so low;

They tossed it over the old Jew’s gates,

And broke the old Jew’s window.

“The old Jew’s daughter she came out;

Was clothed all in green.

‘Come hither, come hither, you young Sir Hugh,

And fetch your ball again.’

“‘I dare not come, nor will I come,

Without my schoolfellows come all;

And I shall be beaten when I go home,

For losing of my ball.’

“She ‘ticed him with an apple so red,

And likewise with a fig:

She threw him over the dresser board,

And sticked him like a pig.

“The first came out the thickest of blood,

The second came out so thin;

The third that came the child’s heart-blood,

Where’er his life lay in.

“‘O spare my life! O spare my life!

O spare my life!’ said he:

‘If ever I live to be a young man,

I’ll do as good chare for thee.

“‘I’ll do as good chare for thy true love

As ever I did for the King;

I will scour a basin as bright as silver,

To let your heart-blood run in.’

“When eleven o’clock was past and gone,

And all the schoolfellows came home,

Every mother had her own child,

But young Sir Hugh’s mother had none.

“She went up Lincoln and down Lincoln,

And all about Lincoln street,

With her small wand in her right hand,

Thinking of her child to meet.

“She went till she came to the old Jew’s gate,

She knocked with the ring;

Who should be so ready as th’ old Jew herself

To rise and let her in.

“‘What news, fair maid? what news, fair maid?

What news have you brought me?’

. . . . . . .

. . . . . . .

“‘Have you seen any of my child to-day,

Or any of the rest of my kin?’

‘No, I’ve seen none of your child to-day,

Nor none of the rest of your kin.’”

I am very anxious to complete this ballad from Northamptonshire; and I again renew my request that some of your correspondents will endeavour to supply what is deficient. The “old lacemaker” would have given more, but she could not. The pure Saxon of this ballad is beautiful.

Cowper got no answer to his request until J.L.C.’s entry in 1868 jogged the memory of Edward Peacock (1831-1915) of Bottesford Manor, near Lincoln. He supplied a full version of the ballad from a Mr W.C. Atkinson of Brigg, Lincolnshire (who had previously published it in The Athenaeum of 19 January 1867, though whether he heard it or discovered a manuscript or print version is not clear). This fills in some of the elements of the narrative: the mother calls her son and his body miraculously speaks, enabling her to find it hidden in a “deep draw-well.” In other versions bells ring and books read themselves as the body is transported. Peacock explained in his article that the ballad bears some relation to events that occurred in 1255 in Lincoln, when the Jews of that city were accused of the ritual murder of a Christian boy, Hugh son of Beatrice, the future ‘Little Saint Hugh of Lincoln’. Nineteen members of the Jewish community would be executed in consequence. The story occurs in three contemporary chronicles, as well as in an Anglo-Norman ballad, and would be referred to in Chaucer’s ‘The Prioress’s Tale’. It is only one of several medieval child saint legends of a related kind (William of Norwich, Robert of Bury St Edmunds, Harold of Gloucester…). Yet while the story was old, there is no record of this particular ballad text until Thomas Percy printed a copy, supposedly from a Scottish manuscript, in his Reliques of Ancient English Poetry: Consisting of Old Heroic Ballads, Songs, and Other Pieces of our Earlier Poets (1765). Thereafter, the ballad has been recorded frequently, in Scotland, England, Ireland and the United States; it has 295 entries in the Roud Folksong Index, the source of the Roud numbers given in this article (and available online at the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library a mine of information on everything related to folk music). The modern ballad differs considerably from the medieval saints’ legends, not least in the primary role played by a woman as siren and murderer.

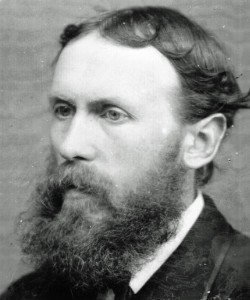

Lacemakers continued to sing this song while making lace well into the later nineteenth century, for Thomas Wright (1859-1936) of Olney, in The Romance of the Lace Pillow (1919) recorded versions from Weston-under-Wood and Haddenham, both in Buckinghamshire, which were used as lace tells in the lace schools. This is the text of one he gave in full.

THE JEWESS MAIDEN.

There was a Jewess maiden, or so my story states,

Who beckoned to a little boy who peeped between her gates.

An apple so red, a plum so sweet, she gave him from her tree;

She dazzled his eyes with a garry gold ring that was so fair to see.

And when she got him in the gates she laughed, he knew not why,

And uttered many wicked words and told him he must die.

She laid him on the dresser board, no mercy then she showed,

But stabbed him with a knife and stabbed until the life-blood flowed.

Wright emphasised that lacemakers’ songs and tells, particularly those from Buckinghamshire, “abound in allusions to coffins, shrouds, corpses, bones, lightning flashes, sardonic laughter, hyena-like cries, and other lurid, gruesome, clammy or grizzly terrors”. The next lacemakers’ song to appear in Notes and Queries makes his point very aptly.

Thomas Wright, schoolteacher and writer of Olney, Buckinghamshire (from Olney and District Historical Society website).

J.L.C.’s reference to the ballad of ‘Sir Hugh’ prompted Cowper to return to the theme of lacemakers’ songs in Notes and Queries of 19 September 1868.

LACEMAKERS’ SONGS: “LONG LANKIN.”

Forty years ago, when in Northamptonshire, I used to hear the lacemakers sing the now well-known ballad of “Hugh of Lincoln” (“It rains, it rains,” etc.) Another, which I have never seen in print, but which I happen to have in MS., is “Long Lankin,” of which I send a copy. Like the damsels whom Shakespeare represents as “chanting” the song which the Clown proceeds to sing (in Twelfth Night, Act II., c. 4), the equally “free maids” of my childhood’s days often chanted, rather than sung, as they sat in rows “in the sun” or in the “lace-school,” an institution which is perhaps effete. But Shakespeare’s lacemakers made “bone lace,” and not “bobbin lace,” with which only I am acquainted. I could perhaps remember some few other ditties which the lacemakers used to sing, though my impression is that they were often mere childish nursery rhymes like “Sing a song of sixpence.” Such probably was one which began in this way:

“I had a little nutting-tree,

And nothing would it bear

But little silver nutmegs

For Galligolden fair”

of which I recollect no more, but that, as a little boy, I used to tell them to say “nutmeg-tree,” which they obstinately refused to do. By-the-way, there was a long piece about “Death and the Lady,” which the “free maids” used to chant. This exhausts my present reminiscences so I shall proceed to give you “Long Lankin”: —

“Said my lord to his lady as he got on his horse.

‘Take care of Long Lankin, who lives in the moss.’

Said my lord to his lady as he rode away,

‘Take care of Long Lankin who lives in the clay.

The doors are all bolted, and the windows are pinned,

There is not a hole where a mouse can creep in.’

Then he kissed his fair lady as he rode away;

For he must be in London before break of day.

The doors were all bolted, the windows all pinned,

But one little window where Lankin crept in.

‘Where’s the lord of this house?’ said Long Lankin.

‘He is gone to fair London,’ said the false nurse to him.

‘Where’s the lady of this house?’ said Long Lankin.

‘She’s in her high chamber,’ said the false nurse to him.

‘Where’s the young heir of this house?’ said Long Lankin.

‘He’s asleep in his cradle,’ said the false nurse to him.

‘We’ll prick him, we’ll prick him all over with a pin,

And that will make your lady come down to him.’

They pricked him, they pricked him all over with a pin,

And the false nurse held a basin for the blood to drop in.

‘O nurse! How you sleep, and O nurse how you snore!

You leave my son Johnson to cry and to roar!’

‘I’ve tried him with suck, and I’ve tried him with pap;

Come down, my fair lady, and nurse him in your lap:

I’ve tried him with apple, and I’ve tried him with pear;

Come down, my fair lady and nurse him in your chair.’

‘How can I come down, it’s so late in the night,

And there’s no fire burning, or lamp to give light?’

‘You have three silver mantles as bright as the sun;

Come down, my fair lady, all by the light of one.’

‘Oh! spare me, Long Lankin, spare me till twelve o’clock!

You shall have as much money as you can carry on your back.

Oh! spare me, Long Lankin, spare me one hour!

You shall have my daughter Nancy, she is a sweet flower.’

‘Where is your daughter Nancy? she may do some good;

She can hold the golden basin to catch your heart’s blood.’

Lady Nancy was sitting in her window so high,

And she saw her father as he was riding by:

‘O father! O father! don’t lay the blame on me;

It was the false nurse and Lankin who killed your lady.’

Then Lankin was hung on a gallows so high,

And the false nurse was burnt in a fire close by.”

To the best of my recollection this copy is not quite complete, and it was sung with occasional ad libitum variations, as “Sally” or “Betsy” for Nancy. It is probable that inquiry in the lace-making districts would produce copies of other old ballads.

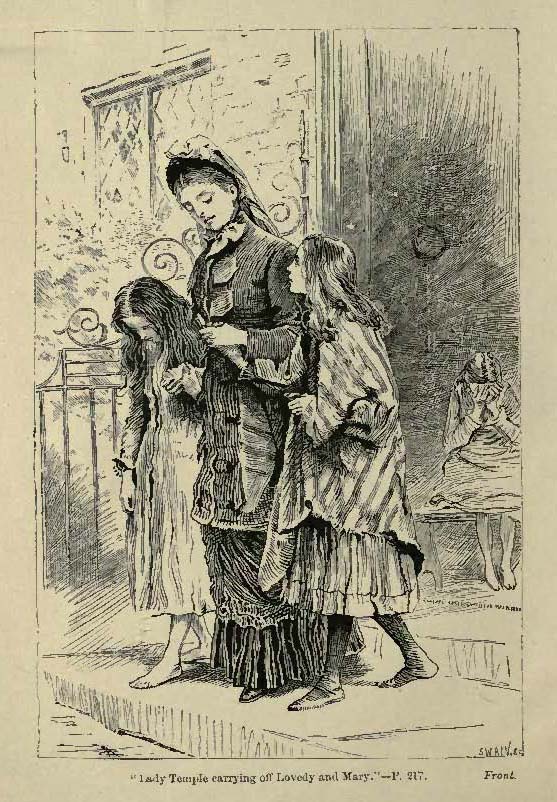

A mid-late nineteenth-century broadside of ‘Death and the Lady’ printed by G. Henson of Northampton (from Broadside Ballads Online, Bodleian Libraries)

Readers will probably be familiar with ‘I had a little nut tree, nothing would it bear’ (Roud 3749). ‘Death and the Lady’ (Roud 1031) was a commonly encountered ballad — or rather ballads, for there are a number of different texts that share a very similar theme. It had often appeared on broadsides from the seventeenth century onwards, and was framed as a dialogue between a fine lady and Death, in which the certainty of the grave, and the judgement beyond, is gradually forced on the former. The final verse in the version supplied by Lucy Broadwood’s English Traditional Songs and Carols (1908) returns us to subtitle of this website:

The grave’s the market place where all must meet

Both rich and poor, as well as small and great;

If life were merchandise, that gold could buy,

The rich would live — only the poor would die.

‘Long Lankin’ (Child 93, Roud 6) had also previously appeared in Notes and Queries for 25 October 1856, when M.H.R. asked for information about the ballad ‘Long Lankyn’ “which is derived by tradition from the nurse of an ancestor of mine who heard it sung nearly a century ago in Northumberland”. Lankin (or Lamkin, or Lammikin, or Beaulampkins, or Lambert Linkin, or Bold Rankin… he goes by many names) is a particularly ghoulish ballad, frequently recorded in the English (and Scots) speaking world. In longer versions of the ballad the eponymous villain is a mason who builds a castle for a nobleman, who subsequently forgets to pay his bills. Perhaps because of its brutality, commentators have often speculated on a medieval origin, but in fact the earliest recorded version, ‘Long Longkin’ was noted from one of his female parishioners by the Reverend Parsons of Wye, near Ashford in Kent, and sent to Thomas Percy of Reliques fame in 1775. Another version appeared the following year in the second edition of David Herd’s Ancient Scottish Songs, Heroic Ballads etc.

Neither ‘Sir Hugh’ nor ‘Long Lankin’ were only, or even primarily, sung by lacemakers. There were part of the common ballad culture of the English and Scots speaking world in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, if not before. It may be worth mentioning that Thomas Percy, who wrote Reliques of Ancient English Poetry while vicar of Easton Maudit in Northamptonshire, close to local centres of lace-making, nonetheless never mentions the penchant of lacemakers for old songs. However, there are some good reasons why the contributors to Notes and Queries should associate these type of songs specifically with lacemakers. The practice of singing while lacemaking was noted by several commentators after Shakespeare. For instance, Thomas Sternberg (probably Vincent Thomas, 1831-1880, who grew up in Northampton and was later librarian of Leeds Library), in his The Dialect and Folk-Lore of Northamptonshire (1851) wrote under the entry ‘Lace-Songs’ that “Lace making is almost always accompanied with singing”.

One might imagine that before machines drowned out the human voice and commercial recorded music became ubiquitous that practically all work, and many other human activities, were accompanied by song. However, from the evidence available, this was not the case. Some occupations in England were frequently associated with singing — they include carters and shoemakers, as well as Shakespeare’s trio of spinners, knitters and lacemakers — but no such association was made with carpenters, blacksmiths or dressmakers. This is not to say that there were not melodious blacksmiths or lyrical carpenters, but that singing was not commonly thought to be an inherent part of their work. A blacksmith’s repertoire would be individual, whereas lacemakers’ was an expression of their collective identity. Hence Sternberg use of the term of “lace-songs”: he associated a particular repertoire with this manufacture. Lacemaking was not so arduous that it prevented the simultaneous use of the lungs, and as pillows were portable it was often done in company, so that singers had both an audience and an accompaniment. And in lace schools, songs or “tells” were used as part of the training process, a topic we’ll return to in a later post. This occupational tradition explains why it was logical for Cowper to suggest that “inquiry in the lace-making districts would produce copies of other old ballads”.

Aranda Dill’s eerie illustration of ‘Long Lankin’ (from Tumblr).

But why these blood-soaked songs in particular? Both ‘Sir Hugh’ and ‘Long Lankin’ are about the murder of a child, specifically the long drawn out death by blood letting. And although the perpetrators might be punished, in lacemakers’ versions the emphasis is very much on the butchering of Hugh and Johnson rather than the retribution that might follow. It is particularly striking that in three cases the contributors to Notes and Queries cited children’s nurses as their original source, especially so in the case of ‘Long Lankin’ where a treacherous nurse is the murderer’s accomplice. Perhaps, like lullabies (think of ‘Rock-a-bye Baby’), these songs were a cathartic release of the repressed resentment felt by servants against the object of their attentions — weak but demanding, dependant but socially superior. Mothers too could feel that children were burdens, a topic we’ll return to in a future post about lacemakers and infanticide. Is it possible that resentment also underlay lacemakers’ performances of ‘Sir Hugh’? Lacemakers were frequently working ten-hour days, if not more, by the age of six: perhaps they were not that sympathetic towards schoolboys playing football. Again it is worth noting that it is a male child who is killed, while in the case of ‘Long Lankin’ the female child survives. We last see Nancy, or Sally, or Betsy, sitting at her window, exactly where, in contemporary descriptions, we find lacemakers working. Perhaps the substitute names allowed different girls to express their own frustrations against their mothers, the person who had set them to lacemaking, and their siblings, and especially brothers whose situation, even if not petted and spoiled, was probably less restricted than lacemakers.

Gerald Porter argues that in lace tells “the theme of child death is implicit, and this relates it [the tell] to a large group of songs in which labor and early death are linked.” Lacemakers sang about child death, while their own autonomy and even their health was being sapped by the very process in which they were engaged. Singing at work is very much part of “the romance of the lace pillow”: the “free maids” sitting in the sun outside a cottage door; but the actual content of lacemakers’ repertoire of songs undercuts this idyll. No doubt singing was a moment of freedom, of “fancy” (as some recent scholars of work-song express it), when imagination was allowed to wander in very different circumstances to those of lacemaker. But in a culture where even looking up from the pillow might be punished, songs might also express a rage that could find no other outlet.

Further Reading: from Notes and Queries.

Clifton Barry, ‘Notes on Midland County Minstrelsy’, Notes and Queries, 1st series VIII (October 1853), pp. 357-8.

B.H.C., ‘The Ballad of Sir Hugh, Etc.’, Notes and Queries, 1st series VIII (December 1853), p. 614.

B.H.C., ‘The Ballad of Sir Hugh.’, Notes and Queries, 1st series XII (December 1855), pp. 496-7.

J.L.C., ‘A Lacemakers’ Song’, Notes and Queries, 4th series II (July 1868), p. 8.

Edward Peacock, ‘A Lacemaker’s Song’, Notes and Queries, 4th series II (July, 1868), pp. 59-60.

Sidney Beisly, ‘Lacemakers’ Songs’, Notes and Queries, 4th series II (August 1868), p. 178

B.H. Cowper, ‘Lacemakers’ Songs: “Long Lankin”’, Notes and Queries, 4th series II (September 1868), p. 281.

Further Reading: other sources

Lucy Broadwood, English Traditional Songs and Carols (London, 1908).

Francis James Child, The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, 5 vols (Boston, 1882-1898).

Mary-Ann Constantine and Gerald Porter, Fragment and Meaning in Traditional Song: From the Blues to the Baltic, (Oxford, 2003), chap. II, ‘Singing the Unspeakable’.

Vic Gammon and Peter Sallybrass, ‘Structure and Ideology in the Ballad: An Analysis of “Long Lankin”’, Criticism: A Quarterly for Literature and the Arts 26:1 (1984), pp. 1-20.

Anne Gilchrist, ‘Lambkin: A Study in Evolution’, Journal of the English Folk Dance and Song Society 1:1 (1932), pp. 1-17.

David Gregory, Victorian Songhunters: The Recovery and Editing of English Vernacular Ballads and Folk Lyrics, 1820-1883 (Lanham, 2006).

Joseph Jacobs, ‘Little St. Hugh of Lincoln: Researches in History, Archaeology, and Legend’, reprinted in Alan Dundes (ed.) Blood Libel Legend: A Casebook in Anti-Semitic Folklore (Wisconsin, 1991), pp. 41-71.

Marek Korczynski, Michael Pickering and Emma Robertson, Rhythms of Labour: Music at Work in Britain, (Cambridge, 2013).

Gavin Langmuir, ‘The Knight’s Tale of Young Hugh of Lincoln’, Speculum 47:3 (1972), pp. 459-482.

Thomas Percy, Reliques of Ancient English Poetry: Consisting of Old Heroic Ballads, Songs and Other Pieces of our Earlier Poets (London, 1765).

Gerald Porter, ‘“Work the Old Lady out of the Ditch”: Singing at Work by English Lacemakers’, Journal of Folklore Research 31:1-3 (1994),pp. 35-55.

Emma Robertson, Michael Pickering and Marek Korczynski, ‘“And Spinning so with Voices Meet, Like Nightingales they Sung Full Sweet”: Unravelling Representations of Singing in Pre-Industrial Textile Production’, Cultural and Social History 5:1 (2008), pp. 11-31.

E.M. Rose, The Murder of William of Norwich: The Origins of the Blood Libel in Medieval Europe (Oxford, 2015).

Thomas Sternberg, The Dialect and Folk-lore of Northamptonshire (London, 1851).

James R. Woodall, ‘“Sir Hugh”: A Study in Balladry’, Southern Folklore Quarterly 19 (1955), pp. 78-84.

Thomas Wright, The Romance of the Lace Pillow (Olney, 1919), Chap XIV: ‘The Lace Tells and the Lace-Makers’ Holidays’.