Frieda Sorber, Wim Mertens, Marguerite Coppens et al. P.LACE.S – Looking Through Flemish Lace. Tielt: Lannoo, 2021, 256 pp.

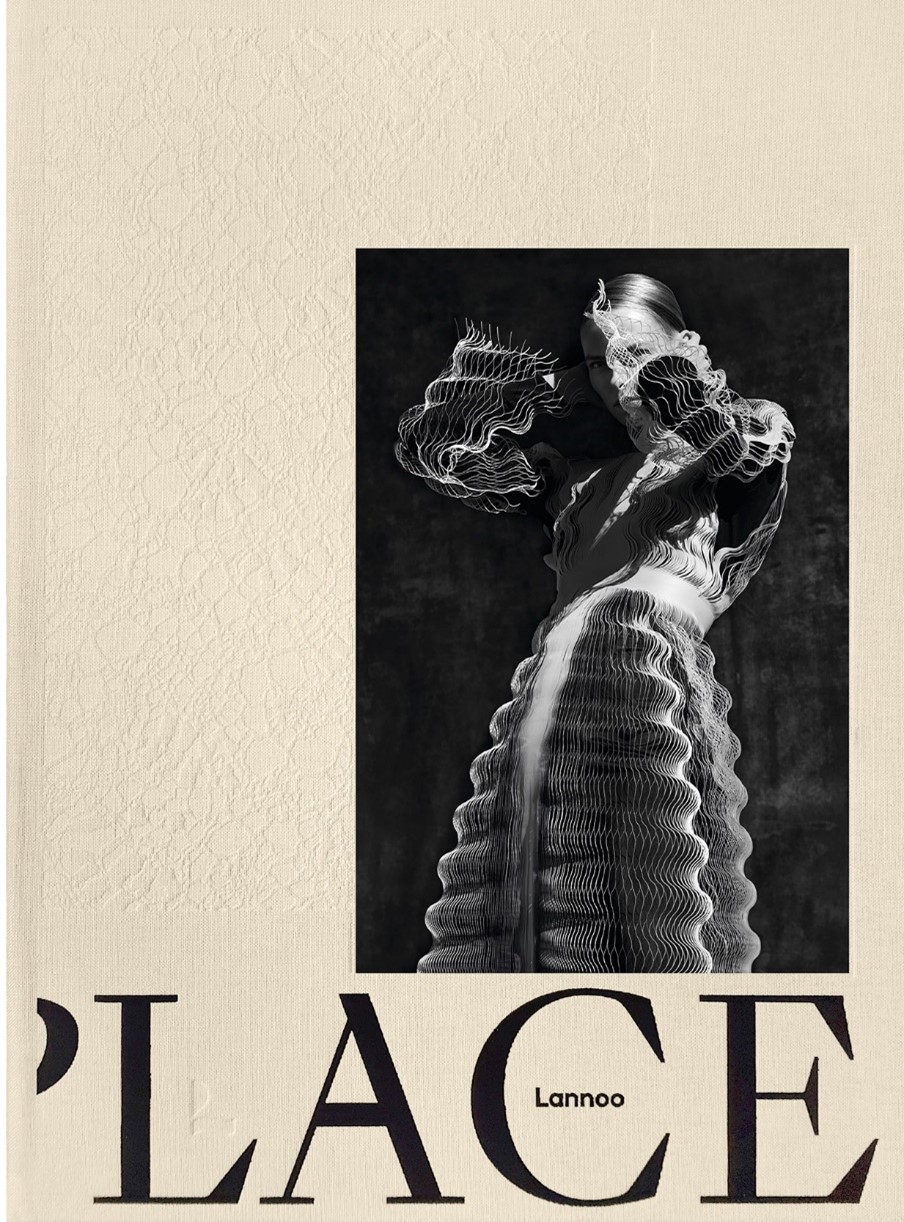

Ill. 1 Front cover P.LACE.S – Looking Through Flemish Lace

P.LACE.S – Looking Through Flemish Lace highlights the socio-economic and artistic importance of the lace that was, over centuries, created and traded in Antwerp. The book argues that, from the mid-sixteenth to the mid-eighteenth century, Antwerp played a leading role in the creation and distribution of lace. However – in contrast to other cities of the Low Countries, such as Brussels or Mechelen – Antwerp’s name was not attached to any particular type of lace. This lack of name branding is, according to the book’s authors, one of the main reasons why Antwerp has been largely neglected in publications on lace.

P.LACE.S aims to reveal how Flemish lace was prominent in fashion, interior design and religion, and that Antwerp, the largest city in the Flemish-speaking half of Belgium, played an important role in its production and commerce. The authors bring together and contextualise historical lace, paintings and archival documents from both European and American collections. In addition, this book seeks to present the history of lace in a dialogue with contemporary, often high-tech fashion creations that specifically refer to lace either in form or concept.

The dialogue between past and present is expressed on the front cover showing the 2017 Glitch dress by the Dutch fashion designer Iris van Herpen, in collaboration with architect Philip Beesley, and a detail of a band of bobbin lace dating from the first half of the eighteenth century (Ill. 1). The former is depicted visually, while the latter is displayed in relief. The interplay between the visual and the tactile evokes a textile which intrigues both the eye and the body.

The book corresponds to the exhibition P.LACE.S – Looking Through Antwerp Lace that ran between 25 September 2021 until 9 January 2022 in MoMu, the Antwerp fashion museum, as well as in four other historical locations – or ‘places’ – in the city that highlight the production, trade and consumption of lace.

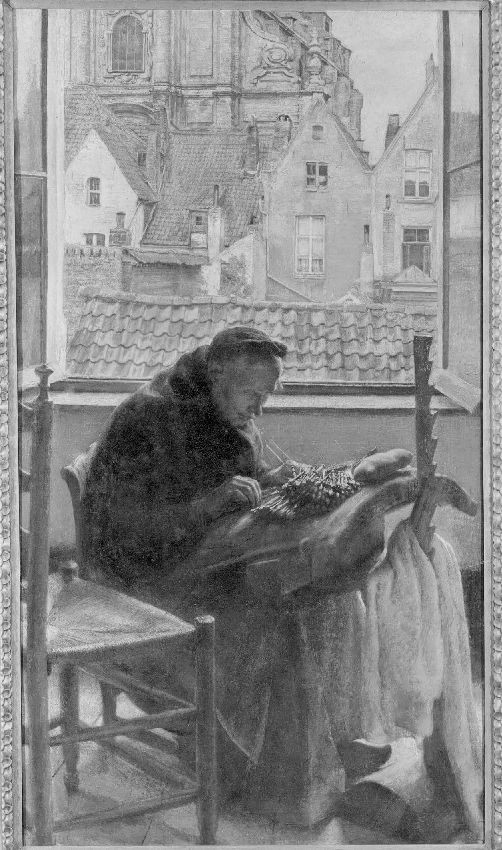

The production and socio-economic aspects of lace were represented in the Maagdenhuis Museum where, at an earlier epoch, the girls’ orphanage of the city was located. The orphanage included a workshop where the girls learned sewing and lacemaking (Ill. 2).

Ill. 2 Lace cushion with pricking, bobbins and lace on display in the Maagdenhuis Museum. Photo: author.

The international trade and the commercial importance of lace was the focal point at the Plantin-Moretus Museum, the original home, workshop and outlet of the Plantin-Moretus family of master printers. One of the world’s oldest archives on the lace trade is kept there. Its holdings provide an insight in the lace and linen trade of the young daughters of Christopher Plantin (1520-1589), whose customers supplied, among others, the French court.

At the St Charles Borromeo Church and the Snijders & Rockox House the spotlight was on the consumption of lace. The Catholic Church in general was an important consumer of lace ever since the textile originated. That explains too why the St Charles Borromeo Church houses an important collection of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century lace. A large part of this collection reflects local creation, enabling an overview of Antwerp lace production and its style evolutions. Another important group of lace consumers were members of the elite for whom lace contributed to the display of their higher status. Such consumers were represented in the Snijders & Rockox House, located in the former homes of the Baroque painter Frans Snijders (1579-1657) and the Antwerp mayor Nicolaas Rockox (1560-1640), the latter belonging to the economic and political elite of the city.

Ill. 3 Alexander McQueen for Givenchy, Jacket with collar in tape lace, Lurex and artificial fibre, haute couture, Autumn-Winter 1998. Photographed by author when the jacket was exhibited in the library of the Plantin-Moretus Museum.

The book P.LACE.S embeds the stories and objects that were displayed at MoMu and the four other locations in a larger history of Flemish lace with an emphasis on Antwerp’s role in its production and trade. After the foreword and the introduction, the book’s content is structured in fourteen chapters that can be divided into four groups, linked by their content.

Five chapters provide a history of lace from its origins to today. These are 1, 6, 10, 11 and 14, and are predominantly written by Frieda Sorber, the former conservator of MoMu. In the first chapter, she explores the origins of lace. Then she delves into the early development of respectively bobbin and needle lace, before drawing attention to the tools needed for lace production. Sorber masterfully connects the many relations between lace and other textile crafts, but she demands from the reader a substantial knowledge of the most important stitches and techniques. Luckily the internet is there for those new to lace who want to follow her trajectory. Sorber’s lifelong engagement with both the study and practice of lacemaking comes to the fore in her discussion of the tools. Through tracing the origins, development and distribution of bobbins, lace pillows, designs, pins and needles across countries, classes and related handicrafts from the Middle Ages to the present, Sorber demonstrates how better and finer tools directly contributed to the evolution of lace as we know it.

Chapter 6, written by Wim Mertens, one of the exhibition curators, concentrates on international lace flows through an examination of the Antwerp entrepreneur Jan Michiel Melijn’s business relations with England in the late seventeenth century. This case study confirms how international trade, including that of lace, was based on mutual trust. The study of Melijn’s correspondence shows how he used his network to set up a lace trade in 1681 and subsequently gained the confidence of local suppliers and new overseas business contacts. He continued the lace trade by providing what the client wished against good prices until war in the Low Countries in the last decade of the century damaged the economy and caused prosperity to wane.

Chapter 10, again by Frieda Sorber, describes how Antwerp missed the boat when the development of part lace in Brussels and Brabant took off from the mid-seventeenth century. Antwerp did not follow this development as local lacemakers and producers probably preferred the known techniques and felt no economic need to innovate. However, Sorber argues in chapter 11 that Antwerp did continue its production and trade by gradually tapping into new markets. After 1750, the city focused on the Dutch niche market and probably on those in parts of Denmark and Germany. But, as she rightly admits, more research is needed to substantiate her hypothesis that there was a lively trade in Flemish lace towards the United Provinces, while the extent of exports to the Danish and German markets remains unknown.

Romy Cockx, one of the exhibition’s curators, also authors Chapter 14, the last historical chapter, in which she seeks to illustrate the parallels between historical lace and contemporary fashion that refer to lace in form and concept. By illuminating visual parallels between needle and bobbin lace as new textile techniques in the sixteenth century and computer-controlled production processes such as laser cutting and 3D printing in the early-twenty-first century, the chapter convincingly demonstrates how lace still inspires today (Ill. 3).

Besides the chronological history of lace production and trade, with their emphasis on Antwerp, four chapters, all written by Wim Mertens, concentrate on specific clothing and household items in lace. Chapter 2 focuses on shirts, albs and rochets, chapter 5 on collars and cravats, chapter 7 on headwear and coiffures and chapter 9 on linen for the lying-in room. In all these chapters, Mertens explores the emergence, evolution, and sometimes the disappearance of such garments. In addition, he pays attention to the way these items were kept and used by persons of different ages, classes and genders (Ill. 4).

Ill. 4 Collar with tassels, decorated with cutwork, embroidery and needle lace, reticella and punto in aria type, 1610-20. Linen, possibly French, 20,3 x 49,5 cm. New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 30.135.147. Photographed by author when the collar was exhibited in MoMu.

Chapter 3 centres on the Brussels and Geneva archdukes’ coverlets, created in the first quarter of the seventeenth century for the archdukes Albrecht and Isabella, rulers of the Spanish Netherlands. Ria Cooreman, responsible for the textile collection at the Royal Museums of Art and History in Brussels, executes an iconographical study of the Brussels coverlet (Ill. 5). By connecting the various scenes depicted in lace with contemporary engravings, she is able to propose a more precise date for its creation. Nora Andries follows up with a technical study of how the coverlet was made. Frieda Sorber ends the chapter with some afterthoughts on both coverlets.

Ill. 5 The Brussels archdukes’ coverlet, 1616-21. Lace, 131 x 174 cm. Brussels, Royal Museums of Art and History, D.2543.00. Photographed by author when the coverlet was exhibited at Snijders & Rockox Museum together with the portraits of the archdukes.

Chapter 3 sets the tone for the remaining chapters which highlight the diverse methods used to investigate lace. In chapter 4, Marguerite Coppens, former curator of the lace collection in the Royal Museums of Art and History in Brussels, attempts to reconstruct Antwerp’s lace industry between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries by consulting archives, written sources and publications. This approach permits her to discover the people involved in Antwerp’s lace manufacture and distribution, while she also shows how the local lace production met the needs of a global market.

In chapter 8, Ina Vanden Berghe describes the technical aspects of materials used in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century lace. Her results are based on fibre analysis executed on samples pieces of lace from MoMu. This analysis demonstrates, among other things, that cotton was already used in Flemish lace in the first quarter of the eighteenth century, much earlier than hitherto thought.

Chapter 12, written by Frieda Sorber, looks at lace in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century doll’s houses as a way to investigate the use of lace in clothing and interiors. The short chapter zooms briefly in on the Puppenstadt, a miniature town called ‘Mon Plaisir’ assembled by Auguste Dorothea von Schwarzburg-Arnstadt, Princess of Schwarzburg-Sondershausen (1666-1751), but it might have benefitted from a comparison with the Dutch doll’s houses (Ill. 6).

Ill. 6 Doll’s house doll of a new mother, with cap, cape and apron in bobbin lace, Antwerp region, Southern Netherlands, c.1680. Linen, height 19 cm. Utrecht, Centraal Museum, 5000/204. Photographed by author when the doll was exhibited at MoMu.

In chapter 13, Wim Mertens provides an overview of the style evolutions in Flemish lace from the late sixteenth- to the mid-eighteenth centuries and concentrates on the floral motif. The evolvement of the motif is embedded into a wider context, considering the production, trade and changes in taste.

Although the individual authors often only apply a singular methodology, the book in its entirety displays a wide range of both traditional and new research methods that push forward our knowledge and understanding of the history of Flemish lace. Their collective efforts transcend the announced methodology of simply bringing together and contextualising historical lace, paintings and archival documents from both European and American collections.

The book is richly illustrated with high-quality photographs of historical lace – regularly accompanied by close-ups – as well as works of art that include lace, archival documents and contemporary fashion creations. Additionally, several illustrations of the latter are depicted throughout the book. They ought to stimulate the dialogue between historical lace and contemporary fashion items with references to lace. Yet to my mind this approach doesn’t quite work as hoped, as the chapters seldom draw direct parallels between laces from the past and high-end fashion items of today, leaving the reader to carry this dialogue mostly on her own.

In conclusion, P.LACE.S – Looking Through Flemish Lace is a rich addition to the history of Flemish lace, filling a lacuna through its focus on the role of Antwerp in the lace production and trade. Its methodology proves how a multidisciplinary approach is beneficial to our knowledge and understanding of this history. At the same time, the book identifies several sites for further investigation, opening up a future for exciting discoveries.

Wendy Wiertz

Dr Wendy Wiertz is a senior research fellow at the University of Huddersfield. In her current project, supported by a Marie Skłodowska-Curie fellowship, she focuses on the humanitarian organisations who saved the renowned Belgian lace industry in the First World War, while simultaneously ensuring the wartime employment of Belgian lacemakers in German-occupied Belgium and among Belgian refugees in Holland, France and the UK. The produced lace became known as war lace, as its unique iconography referred directly to the conflict.