Between Delicate Beauty and Harsh Reality – Lace Ware. An Album 1900–1954

by Herbert Stattler and Martin Bauer.

Translation: Anne Greenwood MacKinney

Lace Ware. An Album 1900–1954, published by Spector Books, Leipzig 2025, ISBN 978-3-95905-884-1

Factor and Factories is one of thirty-eight stories from Lace Ware. An Album 1900–1954 – a book that interweaves the histories of art and economic history in an unusual way.

Following years of meticulous archival investigation, the artist Herbert Stattler created thirty-eight large-format hand drawings, reproduced in the book both in their entirety and as details at original scale. Martin Bauer accompanies each drawing with an essay that sheds light on historical, technical, and art-historical contexts.

The text presented here takes the reader straight into the publishing system of lace production – revealing both the intricate beauty and the hard realities behind this craft.

Factor and factories

Over the course of the nineteenth century, resourceful engineers in England and Switzerland constructed the first machines that could produce such delicate things as lace. Although this quickly enabled the industrial production of these kinds of textiles, lace continued to be made predominantly by hand well into the twentieth century. For three hundred years, this extremely time-consuming activity, which demanded great amounts of manual skill and mental focus, was typically carried out by women in their homes. The lace production was—in socio-historical and economic terms—not a “factory system,” but a “domestic system.” Its importance for the economic development of countries such as Germany, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Italy, France, Spain, Belgium, and Switzerland cannot be overstated. This cottage industry formed a crucial economic sector from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries, with high sales on national and international markets.

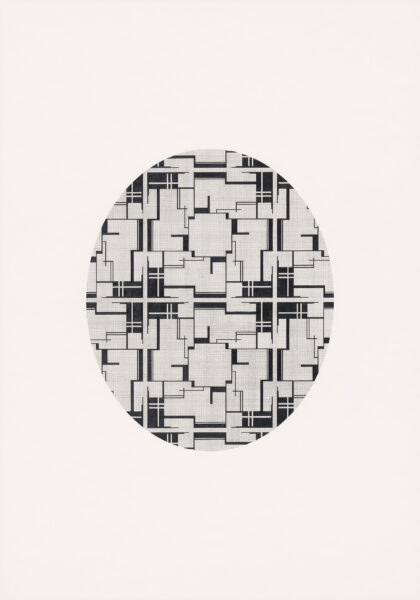

Figure 01: Untitled (122/137), 2024, drawing from the series Lace Ware, pencil on paper, 100 x 70 cm (39.4 x 27.5 in), © Bildrecht Wien

Traditionally, grandmothers, mothers, and their daughters in small farming families supplemented the meager crop yields by selling exquisite embroidery and lace articles that they made by hand. In particularly poor regions, husbands and sons also participated in lacemaking to ensure the family’s livelihood. During the summer months they earned a living as day laborers, while they reserved the months between November and April for domestic work. It was not an ancillary activity to earn additional money, but rather the family’s principal income source and thus an occupation pursued by all able family members, including the old and infirm. It was not uncommon to work up to sixteen hours on weekdays and to rest only on Sundays. Child labor was typical, economically essential, and hence widespread. As early as five or six years old, family members, especially ones with many siblings, had to learn the difficult craft. The earlier they became versed in the various techniques of twisting, braiding, and stitching—skills that were handed down through the family as well as taught in so-called industrial schools—the easier it was for them to make the lace at higher levels of productivity and thereby contribute to the family income. In the Kingdom of Württemberg, the region where Dittmar & Ostertag started its business operations, school-aged children’s curriculum was supplemented by handicraft lessons taught in the hundreds of industrial schools that had been established since the beginning of the nineteenth century. These schools provided needy children with free tools and supplies, but also with an education of strict discipline and hard labor. Their aim was both to cultivate highly skilled craftswomen and to mold obedient subjects. Trained from an early age, these were the daughters who, when they were older, were able to produce lace articles based on new and artisanally complex bobbin lace patterns (Klöppelbriefe) that deviated from traditional manufacturing practices. These laces—elsewhere, for example in Bohemia, called Fassonware—were only made on commission, which is why the production of such articles was remunerated at a different rate than the stock-production of lace. These commissioned laces were highly sought-after items, albeit ones subject to changing fashions, which made the lace market—like that for textiles more generally—extremely volatile in comparison to markets for everyday goods.

To assume that the domestic production of lace provided women with a welcome, if not entirely necessary additional income that they earned on the side while also managing household duties, working the fields, and caring for a small number of livestock—at best, they would own several goats and maybe a cow—would be to wholly misjudge the social and economic reality of this way of life, which was prevalent across parts of Western and Southern Europe. Far from being the leisurely pastime it may have represented for young ladies of the nobility and gentry, the arduous craft of lacemaking was in fact a form of brazen exploitation. The object of this exploitation was not the proletariat, whose suffering in the miserable conditions of the factory system has become paradigmatically associated with the onset of industrialization. At the center of the lace industry were rather wide swaths of a pauperized rural population. Buffeted by high infant mortality, abysmal health care, barren land, repeated crop failures, and a notorious lack of money, these people had no choice. They were forced to mitigate their fundamentally unbearable hardships by making lace.

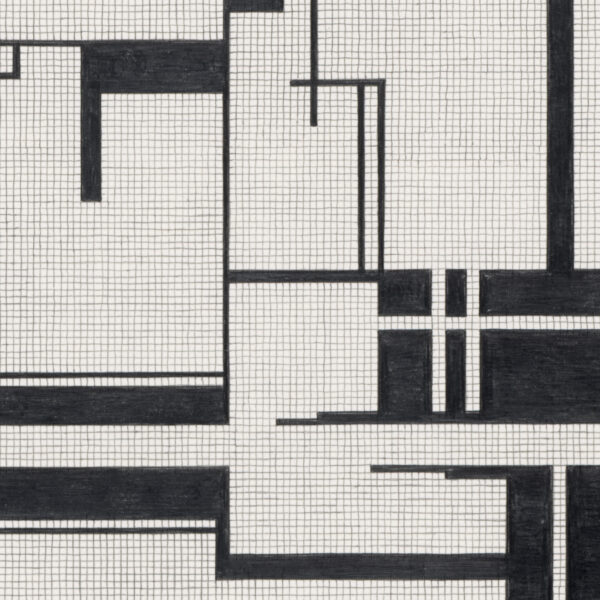

Figure 02: Detail of Untitled (122/137), 2024, drawing from the series Lace Ware, pencil on paper, 100 x 70 cm (39.4 x 27.5 in), © Bildrecht Wien

Economic history identifies the economic structure that determined the everyday life and work of these populations as the “putting-out system,” which is called the Verlagssystem in German. The act of “putting out,” or vorlegen, refers to a grant of credit, or an advance of money. The creditors in this system were traditionally known as Verleger—that is, the same term used in German for publishers. Indeed, today’s publishing sector is an industry that still practices this pattern of economic transaction that had long characterized certain trades before the formation of capitalist modes of production: a bookseller orders books from a publisher, but only pays for them later, for instance after sixty days. Thus, the publisher effectively grants the bookseller a loan equal to the value of the books ordered; as if it were a bank, the publisher advances a sum with the expectation that it will be paid back in a timely manner. With the revenue generated from book sales, the bookseller then repays the debt to its creditor, the publisher. Additionally, any unsold books may be returned to the publisher. The bookseller “remits” the goods and thereby settles the incurred debt without actually making a payment.

In principle, this same logic of credit also applied to the production of lace, although there were regional variations and idiosyncrasies. Put simply, there were five key players: the companies that, despite not producing the lace themselves, misleadingly called themselves “lace manufacturers” and that functioned as the Verleger. As wholesalers, they cooperated on the one hand with retailers, who sold the goods to the end consumers, and on the other hand with so-called factors, who were also called “middlemen” (Zwischenmeister), “foremen” (Vorläufer), or, in Württemberg, “lace saleswomen” (Spitzenverkäuferinnen), since in this region the position was typically held by women who had started their careers as lacemakers. The people working as factors (or the equivalent thereof) knew the trade, were familiar with local conditions, and were in personal contact with the lacemaking families. Accordingly, a factor not only maintained business relationships with the wholesalers, but also with the lacemakers themselves, who typically delivered their products to their factors on a weekly basis. The factor was usually responsible for commissioning the orders for lace articles placed by the wholesale manufacturers, or Verleger. In this respect, the factors were effectively go-betweens, organizing the production of lace according to the wholesalers’ specifications and in some cases storing the lace articles at their own trading posts, or “factories” (in the pre-industrial sense of the term), until they were picked up by representatives of the manufacturers. There were rarely direct relations between the factors and the retailers, which effectively reduced the factors’ dependency on the wholesalers. Factors who also engaged in retail trade were known as peddlers; these vendors undertook trade journeys, selling their wares—which usually encompassed other articles besides lace—from village to village.

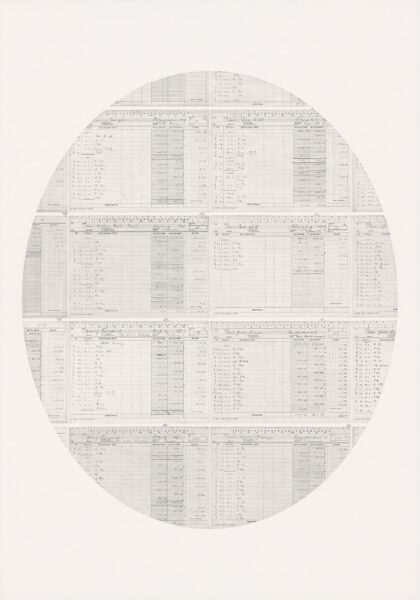

Figure 03: Untitled (Factor and Factories), 2023, drawing from the series Lace Ware, pencil on paper, 100 x 70 cm (39.4 x 27.5 in), © Bildrecht Wien

In order to even be able to begin to make fine lace and embroidered articles, the households that engaged in this kind of work and lacked the necessary funds had to first indebt themselves to the factors. Unable to afford the precious threads often used for lace, these impoverished families relied on the factors to extend them a line of credit in the form of the threads and lace patterns—materials, which the factors, in turn, had received from the wholesalers. Indeed, it was not uncommon for the factories themselves to lack the capital to purchase the threads and patterns outright, leading to the emergence of a multi-level system of debt: the factories were just as much indebted to the wholesalers as the lacemakers were to their factors and as the retailers were to their wholesale suppliers. Only the retailers had the prerogative to remit unsold goods; factors and lacemakers, by contrast, could not return threads that they received from the manufacturers. They had to repay their incurred debts by delivering the lace wares. Factors, of course, charged their lacemakers for the threads—their means of production—at higher rates than those they paid to (or took out as credit from) the wholesale manufacturers. It is impossible to estimate the profit margins between the manufacturers and the factors, and between the factors and lacemakers, because the prices for which these transactions were negotiated remained closely guarded trade secrets. Only vague and imprecise estimates exist, which nevertheless suggest that factors routinely took advantage of those who actually made the lace.

Lacemakers paid off the debts they incurred to the factors by delivering the finished lace products on Sundays. Yet in fact, their wages themselves were, by nature, a kind of repayment of a loan. Officially, lacemakers were considered to be weekly or daily wage earners, but in reality, they were not paid for the hours they worked, but rather for the quantity of lace pieces they produced and the degree of difficulty involved in making these. The more ornate the lace, the higher its value. However, it was not the lacemakers who set the price of their work, but the factors. Their calculations were determined by the profits they hoped to make themselves as factors, as well as by the price and sales expectations of the manufacturers on whose behalf they were working. During periods of extreme economic hardship, the factors sometimes did not even pay in money. Instead, they engaged in a barter system, remunerating the lacemakers’ labor with the basic foodstuffs that would ensure the survival of the families so precariously balanced at the edge of destitution.

Seen in the cold light of day, the lacemaking women were wholly at the mercy of the factors, who, at any moment, could respond to justified claims for payment by withdrawing orders or claiming that the quality of the delivered wares did not meet specifications and therefore could not be remunerated. The producers within the cottage industry of lacemaking had no negotiating power and no meaningful tools for self-representation. The self-organization of domestic workers into trade unions was unthinkable given their isolation in their homes. The criticism occasionally leveled by factors that delivered lace articles “smelled of cowshed” highlights lacemakers’ miserable working conditions, which did not even offer the most rudimentary form of legal security through an employment contract. Thus, it is impossible to describe this misery as a kind of pre-industrial idyll, preferable to the misfortune of exploited industrial factory workers.

Figure 04: Detail of Untitled (Factor and Factories), drawing from the series Lace Ware, 2023, pencil on paper, 100 x 70 cm (39.4 x 27.5 in), © Bildrecht Wien

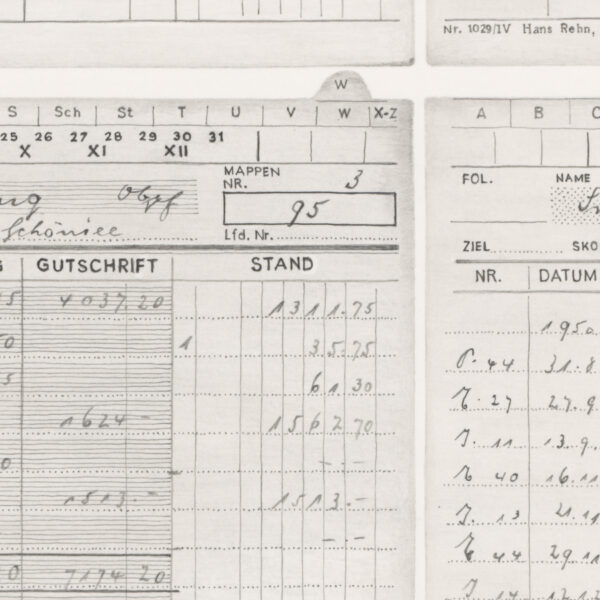

The design of the index cards used by the accounting department in the Stuttgart headquarters of the lace manufacturer can be explained by the putting-out system outlined above. The top line shows the name and location of the factor’s trading post. The date of the order placed with the factor is recorded below, along with the abbreviation for the various designs and patterns for bobbin lace as well as the type (i.e., linen, cotton, silk, or artificial silk) and weight of the threads to be used for the order. On the right-hand side, the debits and credits of the factor are recorded in the traditional form of double-entry bookkeeping, namely the sequence of loan grants and their subsequent repayments. Hundreds of index cards such as these were filed and processed by the accounting department over the course of the company’s history. Considering that each factor, in turn, dealt with a large number of lacemakers, these cards give a sense for the extraordinary complexity of the credit system that provided the economic basis for the production of lace not only in Württemberg, but throughout all of Europe.