Guest post by Júlia Brussi, Federal University of Western Pará, Brasil

In late afternoons, when the sun has already “cooled down” and most of the daily domestic activities have been completed, the lacemakers of Canaan, a district of a small town Trairi, in the state of Ceará in the Brazilian Northeast, put their cylindrical pillows in front of their houses. Alone or in small groups, they handle their bobbins and make their laces while appreciating the refreshing breeze coming from the sea. However, that is not the only time of the day that they dedicate themselves to lacemaking. In fact, they use every single break between their many domestic activities to ‘knock’ their bobbins and make progress their lace (BRUSSI, 2015). During the hottest moments of the day, they search for more ventilated and well illuminated spaces in their house to work in, which usually ends up being the backyard or near the main door.

Lacemakers in the afternoon, while they make lace and chat in front of their houses.

The fact that the production of bobbin lace is mainly a domestic activity is evident to every visitor. However, there are less noticeable aspects that reinforce this relation between the domestic space and lacemaking. They range from the reproduction of the knowledge, the access, or the making of the tools involved in lace making to the commercialization of what has been produced.

A preliminary observation in this regard concerns the spatial distribution of the district of Canaan, which is divided in sectors that could be described as family-based, considering the high concentration of a given family relatives within the same neighborhood. Some of these locations are even named after the local family name, as in the “Ally of the Martins”. Such proximity ensures that a support and mutual help network is maintained between the residents of these places, aspects of which are revealed in the management of daily life, in the raising of children, in the production of lace, and in the reproduction of these skills. The relative isolation of some neighborhoods associated with kinship and gift relations that connect their inhabitants, is even reflected in the quality of the lace produced in each location. There is a family, for example, which lacemakers are known for been experts in doing the lace with a finer thread, that involves a more laborious process. Some families distinguish themselves for producing the lace with ‘half stitch’, which makes the process faster, saves thread, and results in a less firm lace. Others worry about doing the lace with the ‘cloth stitch’ considered by them as more well done lace, even considering that it wastes more thread, that it takes longer, and that these two kind of laces will be sold for same amount of money.

The house, besides being the locus of lace production, is also the main socialization space for children. The constant presence of the pillow in the environment and the daily use that lacemakers make of these objects, associated with the rhythmic movement of lacing, the colors of the threads, and the sound of the beat between the bobbins, raises the children’s interest and curiosity. By playing with bobbins, threads and pillows they learn how to handle the tools and, slowly, they incorporate the necessary skills to make lace. The playing and its daily repetition make them develop the ability to perform all gesture and elementary actions ((ROUX & BRIL, 2002) involved in the production of lace. As they grow up and become interested in the activity, girls are slowly introduced to the different processes that involve the production of a piece of lace. Although the bobbin lace can be learned by children of either sexes (and sometimes it is actually learned by boys), in Canaan, it is eminently a feminine activity.

Aunt and niece making lace on the veranda of a house.

Among the skills that must be learnt and trained by the apprentices, in addition to making the actual lace, there are a series of essential activities, such as the collection, production, or maintenance of the instruments necessary for working on the pillow and the commercialization of the finished work. The cotton thread is the only material that the lacemakers buy in the market, whereas bobbins are usually purchased from residents of the district who specialize in this production selling them from door to door. The bobbins are made from the seed of the tucum palm (Bactris setosa), which must be collected, cleaned, sanded, perforated, and affixed to a previously sculpted wooden spindle. The biggest difficulty is being able to access the palm tree, which is increasingly rare to be found around the district. Lace pillows are usually made by the lacemakers themselves, out of the fabrics of old hammocks, as well as the prickings, although there are also people on the district who offer these products. The banana straw, used to fill the pillow, and the thorns, used as pins, are collected in the vicinity of the district, amid native vegetation. These thorns, originating from a characteristic cactus (Cereus jamacaru) from the native vegetation, are collected once a year, during the dry season. The thorns are more advantageous than the pins, as in addition to leaving the household budget untouched, they don’t rust in the salty air of Trairi and thus, they do not run the risk of staining the lace.

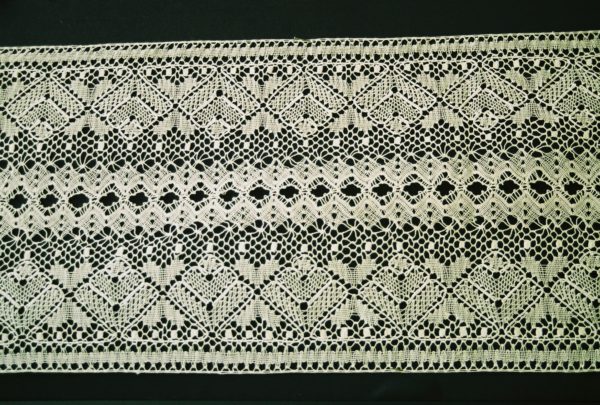

Lacemaker in activity, producing one of the eight strips of lace that composes one shirt.

The sale of the finished laces can also be carried out without leaving the domestic space. It is important to highlight that most of the local production of lace is destined for middlemen, who resell it to market traders on the beaches and in the capital of the state, Fortaleza. Many of these middlemen are local residents, most are women, many of whom are lacemakers (active or inactive), whose economic condition allows them to buy laces to be stored and later resold. It is common for them to visit the lacemakers’ house, or to send their emissaries (daughters, cousins, sister-in-law), to find out if there are finished laces or to place specific orders. Each lacemaker maintains contact with a few of these intermediaries and, if necessary, they can use them even to anticipate small amounts of money.

The household therefore occupies a central place in relation to the bobbin lace activity. There, lace and lacemakers grow and constitute themselves mutually. It is worth remembering at this point about the relation Lave and Wengler (1999) established between apprenticeship, social participation and identity. As the authors point out, the learning process does not only involve the development of certain skills, but implies the formation of a “full participant”, a member of the group, a type of person (LAVE & WENGER, 1999, p. 53). As they are trained in the pillow work, the girls also learn lessons about everything that involves being a good lacemaker, in other words, a “good woman” according to the local conception.

Part of this ethics, this way of being in the world specific to lacemakers, is an aspect that is specifically related to the house. The ideal lacemaker is a woman who keeps herself constantly busy, whether with domestic care or with the lace pillow. The sphere of circulation of that woman should primarily be limited to the domestic space and its surroundings. Her time and body should be, for the most part, occupied and limited. In this perspective, lace is a very effective form of social control over women in Canaan. By remaining active on their lace pillows, the girls are under the supervision and control of their relatives and neighbors. They learn that ‘knocking’ their bobbins, and staying productively busy, is better than watching time going by or wandering in the streets. In contrast to home as known and safe place, the street represents a series of dangers from which mainly young women must be kept at distance.

This does not mean, of course, that there isn’t space for individual choices and actions or that every women conform themselves to these perspectives. The foundation of an Association, the Canaan Lacemakers and Farmers Association, focused on the interests of the lacemakers, in 2005, presents two interesting points in this sense. In the first place, it reflects the mobilization of a group of women whose principal aim was to increase the range of their consumers and the value of their sales. With that goal in mind they expanded their area of circulation, took courses, took part in expositions, and traveled to fairs. Many of them had to face the resistance of their families, who took a negative view of their dedication to the Association and the corresponding reduction of their time home. One lacemaker even separated from her husband since he did not accept her participation in the Association. If we look more closely to the group that takes part of this venture, however, we will see how the pressures of the household and gendered ideals are still effective. Most of those lacemakers who play active role in the Association are separated or widowed, and, thus, do not face the greatest source of resistance faced by the others, a husband. Many don’t have little children anymore, which is also a factor that maintains women at home.

Finally, it is important to highlight that every lacemaker, no matter the scope of their daily circulation or their attachment to the house, seeks though lacemaking a moment of distraction, entertainment, pleasure that, at the same time, allows them financial gain and a greater autonomy. We can suppose that lace constitutes both a form of social control and a potential of liberation, which in addition to contributing to the domestic budget, makes them forget their problems and everyday pressures for a while.

References

BRUSSI, Júlia Dias Escobar. “Batendo bilros”: rendeiras e renda em Canaan (Trairi – CE). Tese de Doutorado, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Antropologia Social da Universidade de Brasilia. Brasília, 2015.

LAVE, Jean; WENGER, Etienne. Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999. (Learning in doing).

ROUX, Valentine; BRIL, Blandine. Observation et expérimentation de terrain : des collaborations fructueuses pour l’analyse de l’expertise technique. Le cas de la taille de pierre en Inde. In: ROUX, Valentine; BRIL, Blandine (Ed.). Le geste technique: réflexions méthodologiques et anthropologiques. Ramonville Saint-Agne: Editions Erès, 2002. p. 29–48.

Špania Dolina was founded in the mid-thirteenth century, when the discovery of an exceptionally high content of copper and silver in the local rock led to the establishment of primitive mines in the local area. In the early 15th century, the powerful Augsburg banking family, the Fuggers, formed the world’s first mining corporation together with the Hungarian Thurzo family, in order to invest in and exploit the riches beneath Špania Dolina (and other villages in the local area). Seeking qualified labour, the Fugger-Thurzo corporation invited German and Bohemian miners familiar with the newest technology of the era to settle in local villages. Špania Dolina – known then as Herrengrund – became the site of a very successful mining business with two large shafts, one accessed directly from the centre of the village. It is thought that the technique of bobbin lace making was brought to the area by the wives of these miners. While the mining industry provided a steady employment for local men for almost three centuries, lace making established itself as a local cottage industry as women supplemented the income of their husbands by making and selling lace.

Špania Dolina was founded in the mid-thirteenth century, when the discovery of an exceptionally high content of copper and silver in the local rock led to the establishment of primitive mines in the local area. In the early 15th century, the powerful Augsburg banking family, the Fuggers, formed the world’s first mining corporation together with the Hungarian Thurzo family, in order to invest in and exploit the riches beneath Špania Dolina (and other villages in the local area). Seeking qualified labour, the Fugger-Thurzo corporation invited German and Bohemian miners familiar with the newest technology of the era to settle in local villages. Špania Dolina – known then as Herrengrund – became the site of a very successful mining business with two large shafts, one accessed directly from the centre of the village. It is thought that the technique of bobbin lace making was brought to the area by the wives of these miners. While the mining industry provided a steady employment for local men for almost three centuries, lace making established itself as a local cottage industry as women supplemented the income of their husbands by making and selling lace.

Lace maker, Sri Lanka

Lace maker, Sri Lanka

Northampton Mercury and Herald, Friday January 19th, 1934.

Northampton Mercury and Herald, Friday January 19th, 1934. Bone bobbin decorated with the name ‘William’.

Bone bobbin decorated with the name ‘William’.  Bone bobbin decorated with the name ‘Fox’. From the collection of the Higgins Art Gallery and Museum, Bedford.

Bone bobbin decorated with the name ‘Fox’. From the collection of the Higgins Art Gallery and Museum, Bedford. Notification from the Bucks Herald reporting Mary Dormer’s theft of twelve bobbins, Saturday July 14th, 1860.

Notification from the Bucks Herald reporting Mary Dormer’s theft of twelve bobbins, Saturday July 14th, 1860.