‘the civilisation of an age may be recorded in the history of trivial things’

The lace pillow on display in the court of the Pitt Rivers Museum was donated by Dame Joan Evans (1893-1977). The provenance is not certain, beyond the fact it came from Milton Keynes in Buckinghamshire. Evans had strong connections to this village, as it still was before 1967, and in particular the lacemaking Hancock family.

Portrait of Dame Joan Evans, painted by Peter Greenham for St Hugh’s College, Oxford. See ArtUK.

Joan Evans was an expert on medieval decorative arts, especially jewellery. She became the first woman President of the Society of Antiquaries in 1959. She was the only daughter of the third marriage (to Maria Lathbury) of the archaeologist and antiquary John Evans (1823-1908), and was thus the half-sister to Sir Arthur Evans (1851-1941), keeper of the Ashmolean Museum and excavator of the Minoan palace of Knossos (deeply loyal to both, she would write their biographies). She grew up in the house attached to her father’s paper mill, Nash Mills near Hemel Hempstead in Hertfordshire. As her parents were often travelling in pursuit of their shared archaeological interests, Evans was effectively brought up by her nanny Caroline Hancock (b. 1864), who arrived when she was eleven months old and would stay with her for the next sixty-seven years, until Hancock’s death in 1961. Evans’ autobiography Prelude and Fugue, started in 1933 but only published in 1964, was dedicated to ‘Nannie’. (For more on the Evans dynasty of archaeologists see the Ashmolean’s John Evans Centenary Project.)

Caroline Hancock’s mother, also Caroline Hancock (1824-1919 née Major), was a lacemaker. (For some genealogical information on the Hancock family, see Nick Hubbard’s website, which also reproduces this chapter together with photos of some of the places mentioned.) Every year from the age of two Evans would spend part of the summer visiting her nanny’s family in Milton Keynes. The chapter dedicated to these annual holidays is worth reproducing in full, because it is by far the most detailed description we have discovered of the domestic arrangements of a lacemaking household in the English Midlands. There are a few points we would highlight along the way: the reference to the kitchen spices reminds us of the spiced cakes consumed at Catterns and Tanders: the engraved bobbins gifted by suitors in her early years (if the bobbins donated to Evans to the Pitt Rivers Museum come from this source, then those suitors may have included a ‘Mark’, a ‘Hiram’, a ‘Thomas’ and a ‘David’); the geraniums around the windows are a regular feature in descriptions of lacemakers’ instinctive desire for beauty; the charity offered to beggars is a regular injunction lacemakers’ songs. Evans’ assertion, after the destruction of the Hancocks’ home by fire, that archaeology requires imaginative reconstruction, is a reference to her half-brother’s controversial rebuilding of the Palace of Knossos.

Nash Mills was not my only home, nor my father’s wife the only woman I called Mother. When I was about two it became evident that both Nannie and I would sometimes need a holiday. My mother, however, was not willing to undertake any responsibility for me while Nannie was away; and so it was decided that I should accompany her on a visit to her family at Milton Keynes in Buckinghamshire. Any decision my mother made was apt to become a binding precedent, and for the rest of my childhood the visit of a month or more was repeated at least once a year.

It is long since I went to Milton Keynes, but my memories of that corner of the earth are still vivid. We went by train to Bletchley, and there we were met by Mrs Claridge, the wife of a small farmer in Milton, with a dog-cart and an old horse that stumbled. Being packed in with some difficulty, off we went, through Bletchley and Fenny Stratford; to Simpson, which had its footpaths raised above the roads and protected by white railings because of floods; through the lanes, till we turned into a high road, and went along by Miss Pinfold’s spinneys to the village. It was – and is – a rather featureless but pleasant bit of England. The villages, with unromantic dissyllabic names – Simpson, Broughton, Woughton, Woolston, Willen – seemed each to be just over a mile from the next. Each clustered round a cross-road and an inn; each had its parsonage and church, its two or three farmhouses, its individual life, centring round the annual feast, when servants were hired and the women were paid for their staple industry of lace making.

Nannie had been born at Woolston, but soon afterwards her parents[1] had moved to an old cottage at Milton. It lay at the end of a path at right angles to the road, on the edge of a great pasture called Barn Close. The barn belonged to the cottage, and was called Babylon; the cottage had no name. You went through a neat green gate, past a small triangular box-edged flower-bed, gay with Shakespearean flowers, along a brick path shaded by damson-trees to the door. It sounds, and seems, an appreciable distance; I suppose it may have been twenty feet. The door was always open, unless it were pouring with rain; inside was the kitchen, with a floor of chequered red and blue tiles, that seemed a natural transition from the bricks outside. One of the joys of Milton was that there was no hard-and-fast line between indoors and outdoors. At Nash Mills we were removed by four long flights of stairs from the garden, and by an unbreakable law I could never go out of doors, even in summer, without changing my shoes. At Milton there was no such rule, and in summer the brick path seemed part of the house and the kitchen part of the garden.

Just inside the door was a wooden table, where the food was prepared, that was scrubbed till it seemed made of no known wood. Above it was an old sweet-smelling corner cupboard, where Mother kept her spices. What cottage nowadays would have the spices Mother kept? Mace and cinnamon, cloves and caraway, nutmegs and black peppers, in a japanned box with radiating compartments; tins of ginger and mustard, dried herbs like fennel and lime (but mint, thyme, and marjoram were used fresh from the garden); sweet and bitter almonds in their skins, tins of currants, sticky blue paper packets of raisins, and vanilla pods in a long glass tube, which were simmered in the custard, dried and used again and again. On the top shelf was the sugar, in tall loaves wrapped in grey paper, that had to be cut with tong-like scissors and broken into lumps with a pestle in the mortar when it was wanted for use. Mother told me once that when she first married sugar cost a shilling a pound, and she had to use honey for sweetening.

Beneath the spice-cupboard was always kept a pail of cool spring water drawn from the well in the garden. Along the other wall stood a noble seventeenth-century chest of carved oak, where linen was stored; and opposite was the open hearth where the cooking was done. Alongside it was the bread oven, in my day only rarely used. It had its own ritual. First you took a faggot of small twigs and burned it in the oven; then you raked out the ashes and cleaned the oven with a wet mop; and then you put the loaves in on a peel, and the cakes in their round tins and the biscuits and ‘little men’ on a tin plate and then the door firmly shut. The ‘little men’ were made from the oddments of pastry. With arms and legs and currant eyes (and, if they were big enough, coat-buttons); they were for the delight of children. All the work involved in shaping them and sticking them with currants makes me realize how rich Mother contrived to be in the most precious commodity of all: time to spend on those she loved.

On the other side of the hearth a passage as long as the chimney was deep led into the living-room. The old windows had been replaced by larger modern ones, and though geraniums (the old-fashioned kind with purply-black spots on the leaves) and calceolarias blossomed on the sill, the room was full of light.

Somehow I was never bored at Milton, though in truth there was not very much to do. Books were few and for the most part pious; fiction was represented by The Story of the Robins, Christy’s Old Organ, Jessica’s First Prayer, and the first two volumes of an old three-volume edition of Richardson’s Pamela. But the garden was solitary enough and wild enough for there to be always something to discover in it: the bloom on a growing apple, that is like powder over the delicate pores of the skin; the early dewberries that grew in one part of the hedge, and the nightshade that climbed over another; the strange ancient smell of hot box; and the fuchsia buds that one could pop with one’s fingers. Musk in those days still smelt sweet, and columbines (which we called straw bonnets) still grew strong and stocky. One may learn to observe as well in lazy hours alone in a garden as among the apparatus of a scientific laboratory.

The end of the garden was called Calais, presumably because it was at the farther side of a wide path. In my day it was derelict; but Mother told me that until lately it had been under corn, and that the grain from it, ground at the mill at Woolston, had provided the flour for her bread.

Nannie’s father had been a carpenter and builder. Years before, when she was a baby, he had fallen from a scaffold and as a consequence of his injuries he had lost his sight. When I knew him as an old man, he sat much in a great chair of his own making by the fire in the living-room; a heavy, massive man, a little slow but very kind. He and I used to go for solemn walks together up and down the bricks, or sometimes he would let me lead him a little farther afield. His eldest daughter, Amy, was blind too, also as the result of an accident; when she was five she had fallen from a swing on to a stone floor, and the optic nerve had gradually perished as a result of the blow. But in her case blindness seemed hardly a disability; she was up and down the house, cooking, cleaning, washing; in and about the garden, digging and picking fruit; in the henhouse, feeding the hens and collecting the eggs; in the barn, to find a tool or whatnot; at the well, to draw water. When she sat down she was just as busy, knitting, crocheting, sewing, making rugs of rag. She had a vigorous character, and might have been a dominating woman but for the love she bore her mother, and her immense generosity of heart to all the world.

Mother was small and neat and nimble. She came of rather better family than her husband; the Majors had been farmers on their own land, and her mother had lived in a house with a French window opening on to the lawn. But the agricultural depression of the forties had hit the Northamptonshire farmers hard, and nothing of this prosperity remained but Mother’s tradition of gentility. She always wore a black lace cap with heavy side-pieces and a kind of crest in front; since her day I have only seen it in the Velay. Over it, if she were working in the garden, she would put on a heavily corded sun-bonnet of lilac print. She wore plain bodices, with a little frill of lace of her own making at the neck, and long full skirts; a print apron in the mornings, and a black silk one and a little three-cornered shawl in the afternoon. She smelt of lavender and fresh air. Her hands were the fine hands of a lace maker; it seemed as if it were by magic that she wove the delicate patterns on the lace pillow, appearing hardly to look at its crabbed pricked parchment pattern and its forest of fine pins. Her bobbins dated from her girlhood; their bone flanks were adorned with the names of the admirers who had given them to her, and some had love-mottoes. Their shanks were wound with bright brass wire in patterns, and the heavier ones for the gimp were dyed red and green. From each bobbin hung a circle of wire weighted with curious red and white glass beads, pressed into half-angular shapes. She excelled in making the fine net ground that had characterized Buckinghamshire lace in the eighteenth century. She had a tolerant contempt for the later Maltese patterns, though she admitted that they gave a better living to the lace maker; yet even so the profit was small, and the cost of the fine linen thread heavy.

Mother was a woman of tremendous courage. When her husband was blinded she had had to support the family, to dig and delve and cut wood and do the work of the husbandman as well as the housewife. She had even taken to butchering in a small way to make a little money. With her own fine hands she would kill a pig and cut it up, sell some, home-cure the hams, and make pork-pies and brawn and faggots and black puddings with the rest. When I knew her the family were in rather smoother waters, but the old habits of thrift still held. It was an exquisite thrift, with nothing sordid about it: based on the old feeling that the work of a woman’s hands in her own home had no value but the negative one of saving money. So every dress was turned and darned, and every scrap of stuff kept for patchwork or rag-rugs; and in cookery every morsel was made the most of. Our chief meal was naturally our midday dinner: a batter pudding baked or boiled, with gravy, and then the morsel of meat that had been stewed for the gravy and some vegetables from the garden. Mother was a great hand at making wines – cowslip, ginger, elderberry, damson, and the like – and I as the visitor would drink some out of a fine cut wine-glass, while the rest drank water. For tea, when I was there, there was often a cake; and for supper, bread and cheese or for a treat a pork-pie. English regional cooking is quickly being forgotten, and few now eat home-made pork-pies in the midland fashion: a dish that any gourmet could enjoy. I still have the recipe for it that Mother gave to Nannie, ending ‘but I need not tell you how to make short crust’. After supper Nannie and I would go to bed in the little bedroom at the top of the steep stairs, and sleep through the summer night on our vast feather bed till morning would come, and we would hear Mother calling to the chickens and Amy moving below, until she came to wake us with a smiling face and soft kisses to the adventure of another day.

Mother had the anima naturaliter christiana. Poor though she was, any beggar that came to her door was given a glass of water, a slice of bread or cake if she had it, and a penny. Every night we read a chapter of the Bible, verse and verse about, thus going gradually through it from beginning to end, genealogies and all. Every Sunday the whole family would go to church, Mother in her bonnet, holding her prayer-book, a clean handkerchief, and a sprig of southernwood. The worst crime was to be late; the only time we were ever hustled was to be ready before the Church bell changed its note and it was time to start.

Church, in itself, I never found particularly interesting. The church was a good plain fourteenth-century building, at that time defaced by having texts painted on tin scrolls fixed above its arches. The orchestra, that had used to play in Nannie’s father’s time, had given place to a squeaky harmonium and the service was decent and dull. It was the hats of the congregation that afforded my chief amusement. The congregation itself I knew well enough, but in the sunbonnets or plain sailor hats of every day. On Sunday everyone appeared in a home-made confection of the utmost interest. The bonnet, or hat, or ‘shape’, was bought in Newport Pagnell on a market day, and trimmed at home, generally out of an ancestral provision of trimmings. The result might be comic but was never banal: and if one had been in Milton long enough one came to know the pièces de résistance among the trimmings, and to recognize permutations and combinations that might have escaped the notice of a casual visitor. The old ladies ran to violets and jet, the middle-aged to wings and feathers, the younger to artificial flowers of great brilliance and improbability, and the children to garlands of buttercups and daisies and terrific ribbon bows; but an unpredictable element always remained.

Evening Church was a treat, chiefly because it meant sitting up late. The twilight lent charm to the building; the lamps of ruby glass, which I thought very beautiful, were lit, and the congregation, from being a congeries of more or less familiar individuals, passed into more solemn and less personal being. The very psalms were unfamiliar; and the walk home, holding Amy’s hand, delightful. Then came a late supper, of such digestible delicacies as pork-pie and pickled onions: and so sleepily to bed.

Mother’s religion was no matter of formal church-going: it entered into everything she did. I never remember her speaking ill of anyone, or doing an unkindness; yet she was never weak nor sentimental. She even had the courage, as an old woman, to face death; she would expend much exquisite darning on an old sheet and say it would do for her shroud, and never made a plan for more than a few days ahead without qualifying it by an ‘if I live’. From her, as at my father’s knee, I learned the wholesome beauties of common sense. Mother had endless tolerance for true eccentricity arising out of character; but for ill-considered foolishness she had one damning comment: ‘I call that a silly caper’.

With all her piety she was a good talker, full of country lore and old saws, some of which I have since found in Thomas Tusser’s Points of Husbandry [first published in 1557]. She could interpret every sign of weather: the sun ‘drawing water’ — that is, casting long visible beams to the earth — the too-golden sunset and the increased range of hearing that meant rain to come; the hour of the change of the moon: ‘the nearer to midnight, the fouler the weather’, and its aspect in the sky, ‘holding water’ with horns upturned, or ‘well up’ with them pointing earthwards. If the slugs were about, she noticed it and prophesied rain; and when the rain came she would foretell if it would last long or not by the cows in Barn Close; if they went into the shelter of the elm trees it would soon be over, and if they stayed out in the field it would last a long time. Each spring we studied the trees to see whether oak or ash budded first, for:

If oak is out before the ash,

Then you’ll only get a dash;

But if ash is out before the oak,

Then you’ll surely get a soak.

Each summer the crop of apples, plums, and gooseberries was judged with as much connoisseurship as the wine-grower expends upon his vintage.

The window of the living-room looked out upon the path that led over the stile across Barn Close; here Mother would work in the afternoons and see every creature that passed by, and guess what took them there. In those days there was only a tiny shop in the village, and the tradesmen from Fenny Stratford regularly called: not merely baker and butcher and grocer, but draper and haberdasher and tailor too. Each was treated in some sense as a visitor, a little conversation was made, a little news exchanged, a little refreshment perhaps offered; and then a polite farewell, and Mother’s pleasant voice saying, ‘Thank you for calling’. Sometimes a strange drummer would come, and hope by briskness and flattery to make us buy something we did not need; but Mother could make short work of him.

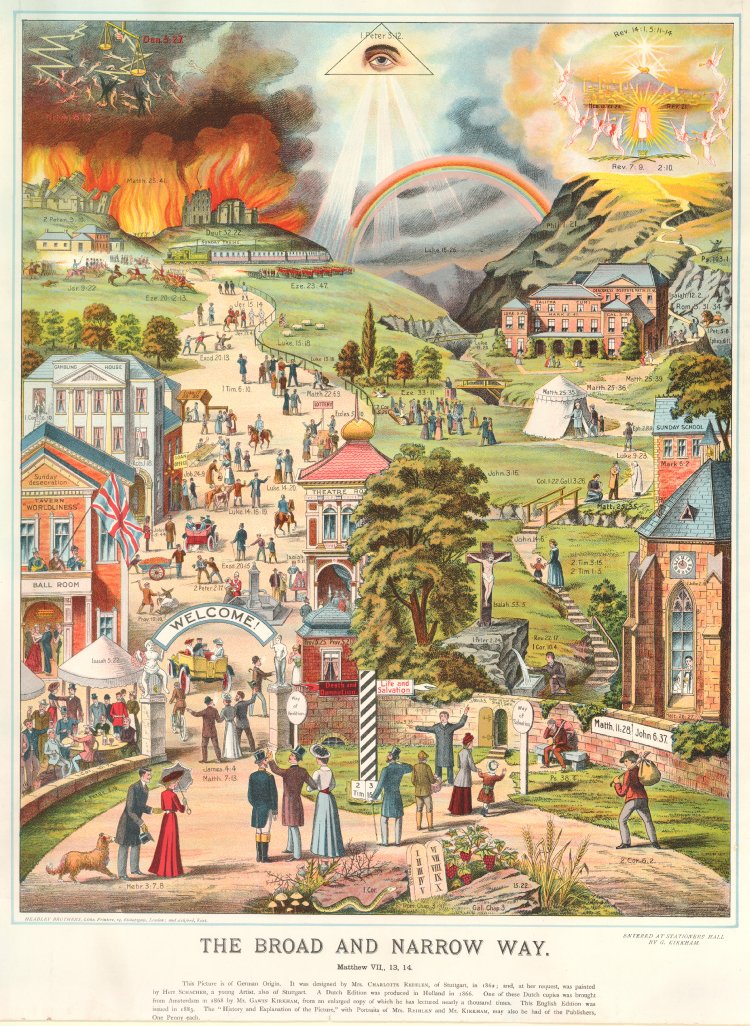

‘The Broad and Narrow Way’, colour lithograph c 1883. Images on this theme circulated widely on the continent. For the details of the ‘people in bustles and top hats’ see the British Museum website.

Amy and Nannie and I did much together. Amy was clever in letting me share in household tasks and in making me feel that I was really helping her; and when it came to choosing the colour of her cotton and threading her needle when she sewed I really was of use. I loved dusting the ornaments in the living-room: the china spaniels with lustred green spots, the pair of pottery birds’-nests full of eggs, which the green serpent was creeping up to steal; the brass candlesticks and the pink glass vases full of dyed grass. That was the moment for studying the pictures: the framed sampler by Rebecca Jackins, and the wonderful coloured print of The Broad and Narrow Way, with people in bustles and top hats painfully toiling towards salvation or cheerfully descending to a Hell too garish to be grim. On hot summer afternoons, when a blessed torpor descended on the house, Amy used to read the New Testament, tracing the raised capitals of her text with work-worn fingers, and letting the beauty of its language be music to her ear. When it was cooler, she and Nannie and I would sally forth for a walk through the fields. The country was not exciting; it undulated in wide shallow valleys, so that one was hardly conscious of the valley, but only of the elm-crowned ridge beyond that limited the horizon. The fields were large, in those days as much arable as pasture: the land poor, the arable full of weeds that I found more interesting than the corn, and the pasture seeming as rich in thistles as in grass. The trees were nearly all in the hedgerows, and mostly elms, with a few ash and oak. The hedges themselves were the most varied part of the landscape, mostly of hawthorn, but studded and draped with holly and elder, wild rose and bramble, ivy and traveller’s joy. The very economy of the landscape drove one to enjoy its details; I can remember learning there more of trees and plants – ash-keys and crab-apple blossom, the caterpillar-like attachments of ivy and the innumerable varieties of wild-rose and blackberry – than I ever did in less barren country. Amy, who had seen none of these things since she was five, seemed none the less to know them all: whereabouts in the hedge blackberries or crab-apples would be found, where wild violets might be hidden in the ditch beneath: and her quick fingers would tell as we passed through the cornfields whether they were sown with corn, or oats, or true barley, or the kind called ‘Hairy Jack’. She could not see the colour change as the straws dipped before the breeze, but she could enjoy the fairy music of the waving oats and the heavier murmur of the bowing corn. Our walks lay all round Milton, and each had its peculiar enticement: a raised causeway of planks over meadows flooded in the winter, a bridge over a slow stream with banks fragrant with meadowsweet and thyme, spinneys where white violets might be found at Easter, a lane with a wide water-filled ditch, with little bridges over it to the cottage gates, a hill-top with a view over to the pinewoods of Bow Brickhill. There were, too, friends whom we might go to visit: Uncle John, who lived at Woolston, who once gave Nannie a Georgian mahogany work-table that we carried all the way home through the fields and over the stiles; an old lace-making friend of Mother’s at Willen, who gave us flowers; and Mrs Holmes, the kind farmer’s wife, who would take us into her dairy and show me how to skim the cream. Apart from these recognized friends, and a few more who lived nearer at hand – Mrs Oakley at the Swan who had beautiful grey corkscrew curls, and Miss Bayliss, who was very kind to Amy – we did not see much of the rest of the village. Mother was a good neighbour, but fastidious in admitting people to intimacy; and indeed the village, that to Squire or parson might have seemed a homogeneous society, had as complicated a scheme of social gradations and as delicate a sense of social nuances as Victorian Mayfair. The parson was a great gentleman – a Wykeham-Twistleton-Fiennes – above these difficulties in virtue of his birth and his generous Christianity; but even so we had a feeling that he felt more at home with Mother than with some people.

I have failed, I know, to recapture the particular aroma of Milton, though sometimes some chance scent or phrase or sound can still transport me there. I cannot give anyone else knowledge of its peace and charity, its old-fashioned mirth and thrift, its limitations and its great heartedness, for they belong to a past chapter of the life of England, that is nearer to the England of the Canterbury Tales than to the England of today. Nor in Milton now can I find even the outward semblance of what was home. For 1909 was a very hot, dry summer, and one day (when we were not there) a long-smouldering beam in the great old chimney burst into flame and fired the thatch. Mother had broken her thigh, and was helpless and bedridden; Amy did what she could, but it was pitifully little. Mother was safely carried out, and some of the furniture from the kitchen and living-room was rescued; but all else disappeared in smoke and fire. The cottage has never been rebuilt. Years later I revisited it. Mother’s flower garden had been overwhelmed in the ruins; the bricks were overgrown; the garden had become a potato field. Only by digging a little in a rubbish heap did I come on a fragment of the familiar chequer of the kitchen floor. How shall an excavator without other knowledge know the fine character and beauty of a civilization thus discovered? I have lived to find a home and a life I have known in ruins; and by virtue of this experience I have lost my faith in any kind of archaeology that does not attempt imaginative reconstruction.

[For the location of the Hancock cottage see Nick Hubbard’s website.]

.