For centuries, lace was primarily produced by the poor for the rich, who ornamented themselves and their dwellings with the luxury fabric. This was also true for Belgian lace, but nevertheless it was promoted as a humanitarian textile during the First World War.

I am a postdoctoral researcher from KU Leuven (Leuven, Belgium) and currently an academic visitor at the Oxford Centre for European History (Oxford, United Kingdom). My research focuses on war lace, lace produced by Belgian lacemakers during the First World War. Some of these lace pieces refer directly to the conflict. They include names of people and places, inscriptions, dates, portraits and coats-of-arms or national symbols of the Allied Nations, of the nine Belgian provinces or of the Belgian towns who suffered most during the German invasion. A few of the distinctive war laces have been designed by Belgian artists – such as Isidore De Rudder (1855-1943), Fernand Khnopff (1858-1921) and Juliette Wytsman-Trullemans (1866-1925) – whose exceptional laces have been studied for their iconography and their aesthetic quality, before being placed within the larger history of lace production in Belgium.[1] However, I am more interested to use war lace as a starting point to explore the relations between craft, women and humanitarian aid.

Juliette Wytsman (designer), Maison Daimeries-Petitjean (manufacturer and dealer), Monogrammed fan leaf with designer’s name, 1915-1916. Point de Gaze needle lace, 5 in x 17 in; 12.7 cm x 43.18 cm. Washington D.C., National Museum of American History.

In early August 1914, Belgium was violently invaded by German troops, who conquered the majority of the country and occupied it for the remainder of the war.[2] The years of occupation meant hunger and unemployment for the circa 7.5 million Belgian civilians.

The supply of food and its distribution became a problem almost immediately. The situation particularly deteriorated in the major cities and industrial areas.[3] In early September 1914, Brand Whitlock (1869-1934), the American minister to Brussels, noted: ‘Then we began to note a new phenomenon – new, at least, in Brussels – women begging in the street. Hunger, another of war’s companions, had come to town.’[4] Local and national initiatives were taken to relieve hunger and to avoid starvation, but they proved to be insufficient. Before the war, more than half of food consumed in Belgium had been imported.[5] This was now impossible, because the closure of the national borders and the installation of the Allied blockade cut Belgians off from the international food market. An international partner who could import food from abroad was sought and found in the Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB), newly established for the purpose. The CRB was an American relief organisation founded and chaired by the engineer, businessman and later 31st U.S. President Herbert C. Hoover (1874-1964).[6] For more than fifty months, the CRB helped feed nearly ten million people, first in occupied Belgium and later also in occupied Northern France. It collected one billion dollars and imported five million tons of food via the port of Rotterdam from where it was transported into the occupied areas. In Belgium their local partner, the Comité National de Secours et d’Alimentation (CN), distributed the food to the towns and municipalities.[7] In spite of these impressive numbers, the food supply and distribution was inadequate. This was especially the case during the second half of the war. After a visit to Brussels in September 1917, the Belgian Countess Henriette de Villermont (1855-1940) noted in her diary: ‘All the fat people have disappeared.’[8] Nevertheless, actual starvation was avoided during the entire war.

Herbert C. Hoover, the later 31st President of the U.S. (1874-1964). Wikipedia.

In addition to food aid, the CRB set up employment schemes, as did other philanthropists, charity organisations and local, regional and national authorities. The need was great: a large part of the Belgian population was hit by unemployment, because many industries remained closed during the occupation. As the Belgian historian Sophie De Schaepdrijver explains ‘The restrictions on imports of raw materials and the exportation of goods, the impossibility of commuting, the ban on communication between citizens of different municipalities, the requisitionings of material, the war taxes and fines, the closure of factories and workshops unwilling to work for the occupiers, and the dismantling of infrastructure, all paralysed honest activity.’[9] Creating employment benefitted not only the worker who once again had an income, but also the CRB’s food aid programme. Unemployed Belgians would receive their daily meal for free, but employed ones were enabled to buy their food. If more people could pay for their foodstuffs, the CRB had more money with which to purchase, import and distribute food.

Employment schemes were particularly concerned with the large sector of women who had been wage-dependent before the war, because they suffered the most from job scarcity. The schemes focussed on women’s activities in the home and they included childcare, cooking, sewing and lacemaking.[10] Before the war the Belgian lace industry had employed circa 50,000 women, who were now (or threatened to be) unemployed due to the shortage of raw materials as well as the dearth of clients: Belgian lace had always been an export product.[11] Associations that had already concerned themselves with lacemakers welfare before the war – they were a notoriously poorly paid group – continued to interest themselves, while new initiatives were introduced to support lacemakers. However, these proved inadequate as the Allied blockade prevented the import of thread and the export of lace from occupied Belgium.[12] The American-born Viscountess de Beughem, née Irone Hare (1885-1979), one of the core members of the pre-war Comité de la dentelle, brought the fate of the lacemakers in occupied Belgium to the attention of Herbert Hoover of the CRB.[13] Years later, she recalled in an interview how she had insisted on meeting Hoover during his visit to Brussels in January 1915. When she did meet him,

‘[h]e said, “It appears you have something to ask me.” And I said, “Indeed I have, Mr. Hoover, and it’s very important.”‘ The viscountess then explained to him the condition of the lacemakers. ‘So Mr. Hoover saw me through, and I thought – there was no reaction whatever. You know how he would sit without any expression. […] And he finally looked and said to me: “I will do what I can.” And during the whole war he brought in the thread on the canals, on the boats that brought in the flour, and took out the lace.’[14]

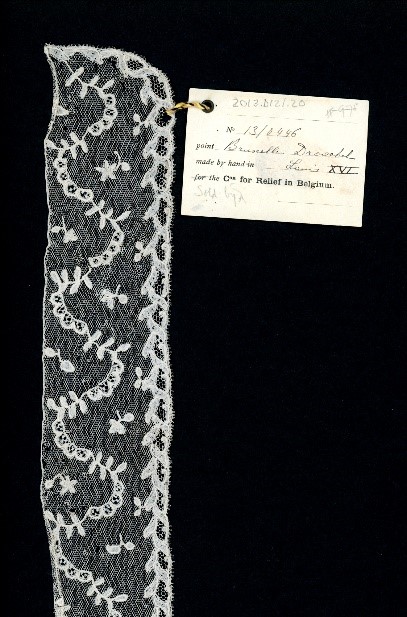

Unknown maker, Collar with attached tag, 1914-1918. Lace, bobbin lace, Brussels, Droschel, overall, lace: 57 in x 2 1/4 in; 144.78 cm x 5.715 cm. Washington D.C., National Museum of American History.

The lace was exported to the U.S. and Allied Countries with France and the United Kingdom as the other main destinations. There the many qualities of the fabric, the wide range of products, the reasonable prices, the renown of Belgian lace, the deplorable situation of the Belgian lacemaker – who nevertheless made the best of her hardship – were pointed out to the buyer.[15] The Little Paris Shop located at the Huntingdon Avenue in Boston used a mixture of these sales strategies in their advertisement of Belgian lace:

Belgian Laces made Belgium Famous. Queen Elizabeth of Belgium has under her protection the Belgian lace makers because the village folks, old and young, mothers and even men make an honest living by it. Belgian laces are durable, washable, wearable for Christenings, marriages, gifts, etc. just beautiful and many times precious. Belgium laces: have a souvenir of it. They are for all pockets from 25c up. Lace makers work in groups from 6a.m. to 7p.m. year after year; they spend their days in work, songs, talks and prayers. They are happy when there is plenty of work.[16]

The Belgian lacemaker quickly became the primary focus of the propaganda (as we have seen in a previous post on their place in First World War poetry). An example is a series of postcards showing Belgian lacemakers practising their craft in their war-ravaged surroundings.[17] One of these postcards depicts a well-fed young woman dressed in simple dark clothes and a white apron, industriously making bobbin lace. Working quietly and seemingly unaware of the viewer’s gaze, she sits in a field with in the background the ruins of a church on the left, a large cross in the middle and seemingly intact buildings on the right. The other postcards show the same type of imagery: female lacemakers of different ages who are well-nourished – thus demonstrating the success of the CRB’s food relief programme – who continue their work proving the heroic stoicism of Belgians living and labouring under the German occupation. The women are pictured in or nearby their lace schools, homes and churches, as if to demonstrate the women’s commitment to their craft, their families and their faith.

Cliché des ‘Amies de la Dentelle,’ A Belgian woman making bobbin lace in front of a destroyed church, ca. 1920. U.S., Palo Alto, CA, Hoover Institution, Commission for Relief in Belgium records, box 640.

Lace had always been a luxury item. In general during times of war or hardship, the production of luxury goods is normally discouraged or even entirely abandoned. This was not the case with Belgian lace, though it was a question raised at the time. After the U.S. entered the First World War in April 1917, opposition increased to luxury expenditure: witness the article ‘How fare the luxuries in war-time?’, published in Printer’s Ink. A New York Journal for Advertisers on 4th October 1917:

One of the very latest features of Belgian relief in which the American authorities are just now interesting themselves, aims to enlist the patronage of American women for Belgian lace workers […] Thus to encourage luxury production in one quarter and discourage luxury production in general in the United States would manifestly be an inconsistent, if not incomprehensible attitude.[18]

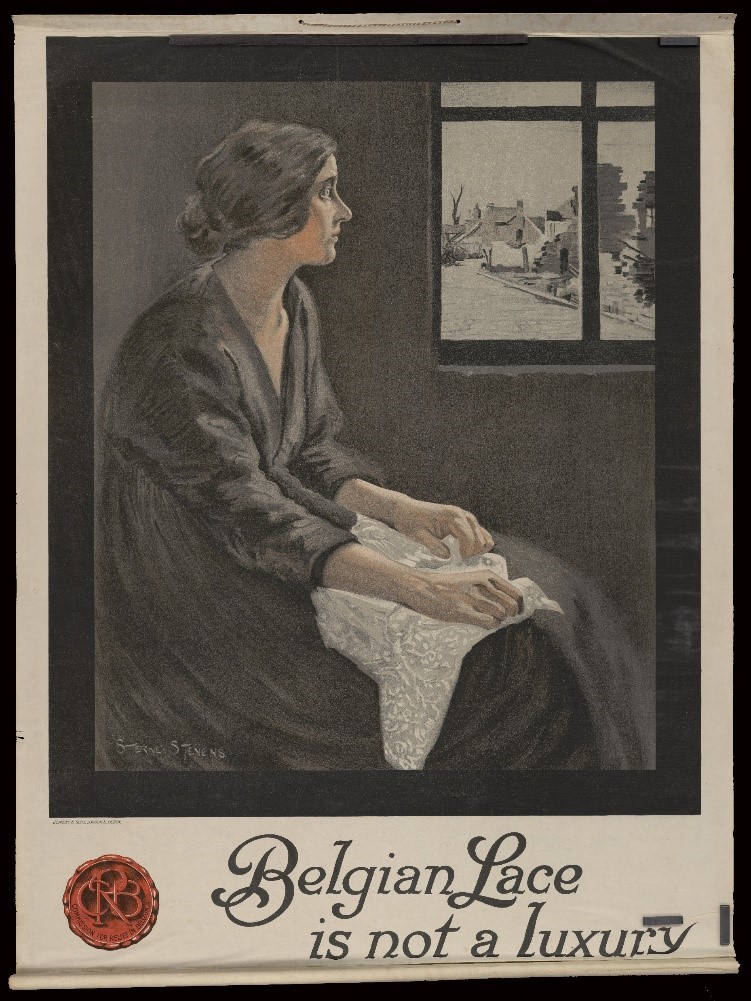

Lawrence Sterne Stevens, Belgian Lace is not a luxury, 1914-1918. Belgium, Brussels, National Archives of Belgium.

This kind of criticism explains why the CRB issued a poster for use in the UK stating ‘Belgian Lace is not a Luxury’. The drawing above the caption immediately pointed the contemporary viewer to what really mattered: the destitute Belgian lacemaker who could only survive in her war-ravaged surroundings thanks to her craft and her international supporters. This strategy diverted attention from lace as a luxury item. Belgian lace was successfully promoted as a humanitarian textile during the First World War.

Wendy Wiertz, postdoctoral researcher KU Leuven | academic visitor Oxford Centre for European History

wendy.wiertz@kuleuven.be | wendy.wiertz@history.ox.ac.uk

[1] Marguerite Coppens, ‘Les commandes dentellières de l’Union patriotique des femmes belges et du Comité de la dentelle à Fernand Khnopff’, Revue belge d’archéologie et d’histoire de l’art 64 (1995), pp. 71-84; Patricia Wardle, ‘War and Peace. Lace designs by the Belgian Sculptor Isidore de Rudder (1855-1943)’, Bulletin van het Rijksmuseum 37: 2 (1989): pp. 73-90; Patricia Wardle, 75x Lace (Zwolle: Waanders, 2000), cat. nr. 75.

[2] Antoon Vrints, ‘“All the Butter in the Country Belongs to Us, Belgians”: Well-Being and Lower-Class National Identification in Belgium during the First World War’, in Maarten Van Ginderachter and Marnix Beyen (eds) Nationhood from Below. Europe in the Long Nineteenth Century (Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan, 2012), p. 234; Sophie De Schaepdrijver, De Groote Oorlog. Het koninkrijk België tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog, 5th ed. (Antwerp/Amsterdam: Houtekiet/Atlas Contact, 2014), pp 13-125; Éliane Gubin and Catherine Jacques with the corporation of Claudine Marissal, Enclyclopédie d’histoire des femmes. Belgique, XIXe-XXe siècles (Brussels: Racine, 2018), pp. 266-73.

[3] Antoon Vrints, ‘Beyond Victimization: Contentious Food Politics in Belgium during World War I’, European History Quarterly 45:1 (2015): 234-5; Giselle Nath, Brood willen we hebben! Honger, sociale politiek en protest tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog in België (Antwerp: Manteau, 2013), 45-63; De Schaepdrijver, De Groote Oorlog, 114-16.

[4] Brand Whitlock, Belgium. A Personal Narrative (New York: D. Appleton, 1919), vol. 1, p. 239.

[5] Nath, Brood willen we hebben!, 45.

[6] Herbert Hoover, The Memoirs of Herbert Hoover, 3 vols (New York: Macmillan, 1951-52); George H. Nash, The Life of Herbert Hoover, 3 vols (New York/London: W.W. Norton & Company, 1983-96); Kenneth Whyte, Hoover. An Extraordinary Life in Extraordinary Times (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2017).

[7] From the start of the food aid programme, the CRB sought publicize its activities through press coverage, posters, reports and overviews, while several American volunteer CRB collaborators wrote about their experiences in occupied Belgium during and shortly after the war. The latter include Tracy B. Kittredge, The History of the Commission for Relief in Belgium, 1914-1917 (London: Crowther and Goodman, 1920); Vernon L. Kellogg, Fighting Starvation in Belgium (Garden City [NY]: Doubleday, 1918); George I. Gay, The Commission for Relief in Belgium. Statistical Review of Relief Operations (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1925); Herbert Hoover, An American Epic, 3 vols (Chicago: Henry Regnery, 1959-61); These publications prioritized American perceptions and expectations of Belgian gratitude, which have sometimes been echoed uncritically by contemporary researchers: Tammy M. Proctor, Civilians in a World at War 1914-1918 (New York/London: New York University Press, 2010), pp. 189-92; Bruno Cabanes, The Great War and the Origins of Humanitarianism, 1918-1924 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014), pp. 206-213; Barry Riley, The Political History of American Food Aid. An Uneasy Benevolence (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), pp. 12-32. Multilingual research on critical voices of national and local committees and of the targets of aid have countered this one-sided American view, adding to a more multifaceted view of CRB food aid in occupied Belgium: Sophie de Schaepdrijver, ‘A Civilian War Effort: the Comité National de Secours et d’Alimentation in Occupied Belgium, 1914-1918’, in Remembering Herbert Hoover and the Commission for Relief in Belgium (Brussels: Fondation Universitaire – Universitaire Stichting, 2006), 26-37; Nath, Brood willen we hebben!, pp. 45-63; Vrints, ‘Beyond Victimization’: 83-107.

[8] Belgium, private archives, diary of Countess Henriette de Villermont kept between 1884 and 1918: ‘4 septembre 1917, les grosses personnes ont disparu’.

[9] De Schaepdrijver, ‘A Civilian War Effort’, p. 32.

[10] Charlotte Kellogg, Women of Belgium. Turning Tragedy to Triumph (New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1917), pp. 127, 137-57, 167-78; De Schaepdrijver, ‘A Civilian War Effort’, pp. 24, 32-35; Éliane Gubin et al., ‘Women’s Mobilization for War (Belgium)’, in Ute Daniel et al (eds) 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2016-09-21; Gubin and Jacques, Encyclopédie d’histoire des femmes en Belgique, 19e et 20e siècle, pp. 266-73; 577-79.

[11] The number of 45,000 to 50,000 are commonly cited. Yet, Isabel Anderson, author of The Spell of Belgium, wrote ‘[w]here a generation ago one hundred and fifty thousand women were employed, in 1910 there were barely twenty thousand.’ Isabel Anderson, The Spell of Belgium, 5th ed. (Boston: The Page Company, 1922), p. 149. There might have been more lacemakers as for many women, the craft was not a fulltime occupation. Therefore, they did not define themselves as lacemakers in the census. Nonetheless, the number of lacemakers diminished drastically in the second half of the nineteenth and the first decade of the twentieth centuries. See also David Hopkin, ‘Working, Singing, and Telling in the 19th-Century Flemish Pillow-Lace Industry’, Textile 18:1 (2020): 55.

[12] Martine Bruggeman, Lace in Flanders. History and Contemporary Art (Tielt: Lannoo, 2018), pp. 88-9.

[13] The Viscountess de Beughem was one of the core members of the CD alongside Countess Élisabeth d’Oultremont (1867-1971), lady-in-waiting to the Belgian Queen Elisabeth; Baroness Josse Allard, née Marie-Antoinette Calley Saint-Paul de Sinçay (1881-1977), an amateur artist and wife of a banker; and Mrs Louis Kefer-Mali, née Marie Mali (1855-1927), an expert on the history of lace, wife of a musician and sister of the Belgian Consul-General in New York. Mrs Brand Whitlock, née Ella Brainerd (1876-1942), who was married to the American minister to Belgium, was appointed as honorary chair. Whitlock, Belgium. A Personal Narrative, vol. 1, pp. 549-50; Evelyn McMillan, ‘War, Lace, and Survival in Belgium During World War I’, PieceWork Spring (2020): pp. 47-8.

[14] U.S., West Branch IA, Herbert Hoover Presidential Library, oral history interview with Vicomtesse de Beughem by Raymond Henle, director, 16 November 1966, at 3945 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Washington D.C. This story was also mentioned by Herbert Hoover in the first volume of his publication An American Epic. Herbert Hoover, An American Epic, vol. 1 Introduction. The Relief of Belgium and Northern France 1914-1930 (Chicago: Henry Regnery, 1959), pp. 410-11. The British were especially reluctant to open the blockade for the trade of Belgian lace. They feared the Germans, who had erected their own lace agency, the Spitzen-Zentrale, might succeed in their efforts to control a revived Belgian lace industry. Kellogg, Women of Belgium, p. 160; Whitlock, Belgium. A Personal Narrative, vol. 1, p. 419; Kellogg, Bobbins of Belgium, pp. 120-23; Marguerite Coppens, Kant uit het Koningshuis, exhibition catalogue Brussels, Bank Brussel Lambert (Brussel: Weissenburch, 1990), pp. 116-19.

[15] Jennifer D. Keene, ‘Americans Respond. Perspectives on the Global War, 1914-1917‘, Geschichte und Gesellschaft 40 (2014): pp. 266-86.

[16] Private collection.

[17] U.S., Palo Alto, CA, Hoover Institution, Commission for Relief in Belgium records, box 640: series of postcards.

[18] ‘How fare the luxuries in war-time?’ Printer’s Ink. A New York Journal for Advertisers, 4 October 1917.