Although we asserted a link between lacemaking and singing in our last post, we don’t have any audio of English lacemakers singing while working which we can share with you (though we’re always hopeful of finding some). In Belgium and France, and especially the Velay region of the Auvergne, the connection between lacemaking and singing is even better attested, and you can listen as well as read some songs from these regions.

Images: A panorama of Le-Puy-en-Velay, dominated by its statue of the Virgin Mary. (Licensed under CC BY-SA 1.0 via Wikipedia Commons)

The Velay (Haute-Loire) was the predominant region for lacemaking in France in the nineteenth century, and outposts of handmade lace manufacture, largely aimed at the tourist trade in Le Puy, could still be found right up to the 1990s (perhaps still). In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries it was also a very important region for folksong collecting. In the 1860s and ‘70s, Victor Smith, a judge from Saint-Etienne, transcribed hundreds of songs from lacemakers as they worked in groups in the street or under the shade of a tree (en couvige in dialect). In the years running up to the First World War, the novelist Henri Pourrat would collect dozens more songs around his home town of Ambert (not in the Velay but in Puy-de-Dôme, but it might be considered an extension of the Velay lacemaking industry). Later still, after the Second World War, the teacher Jean Dumas would tape hundreds of songs from lacemakers. And there are many other audio recordings from the likes of Claudie Marcel-Dubois, Maguy Pichonnet-Andral, Pierre Chapuis and Didier Perre. We may return to some of these in future posts.

However, in one case we have video as well as audio. A short film, ‘Les dentellières de Montusclat’, was made for the French Institut national de l’audiovisuel (INA) in 1978, which you can see for yourself by clicking on the link. It depicts three lacemakers, aged 75, 78 and 85, two of them sisters, chatting and singing while making lace in the mountain village of Montusclat, about thirty kilometres east of Le-Puy-en-Velay. They tell the story of the village, its church, the passage of the plague through the region, and the legend of Notre-Dame de la Salette (a vision of the Virgin Mary who appeared to two children in 1846). They also talk about lacemaking; they started at the trade when they very young, when earnings from lace were necessary to put clothes on their backs and food on the table. Having become habituated to constant work they cannot sit idle; whenever they have a moment they are back at their pillows. And they are still earning a bit of money (one franc an hour!). When talking to each other at the beginning of the film (when the eldest is seen urging the others on to “Work! Work!”) the women speak in the Occitan dialect of the region, but when talking to the filmmaker they speak in French. They also sing in French. Even when Victor Smith was collecting songs in the region over a hundred years previously, at a time when Occitan was far more dominant, lacemakers would often sing in French. Singing was a cultural activity, and so deserved the ‘cultural’ rather than the ‘everyday’ language.

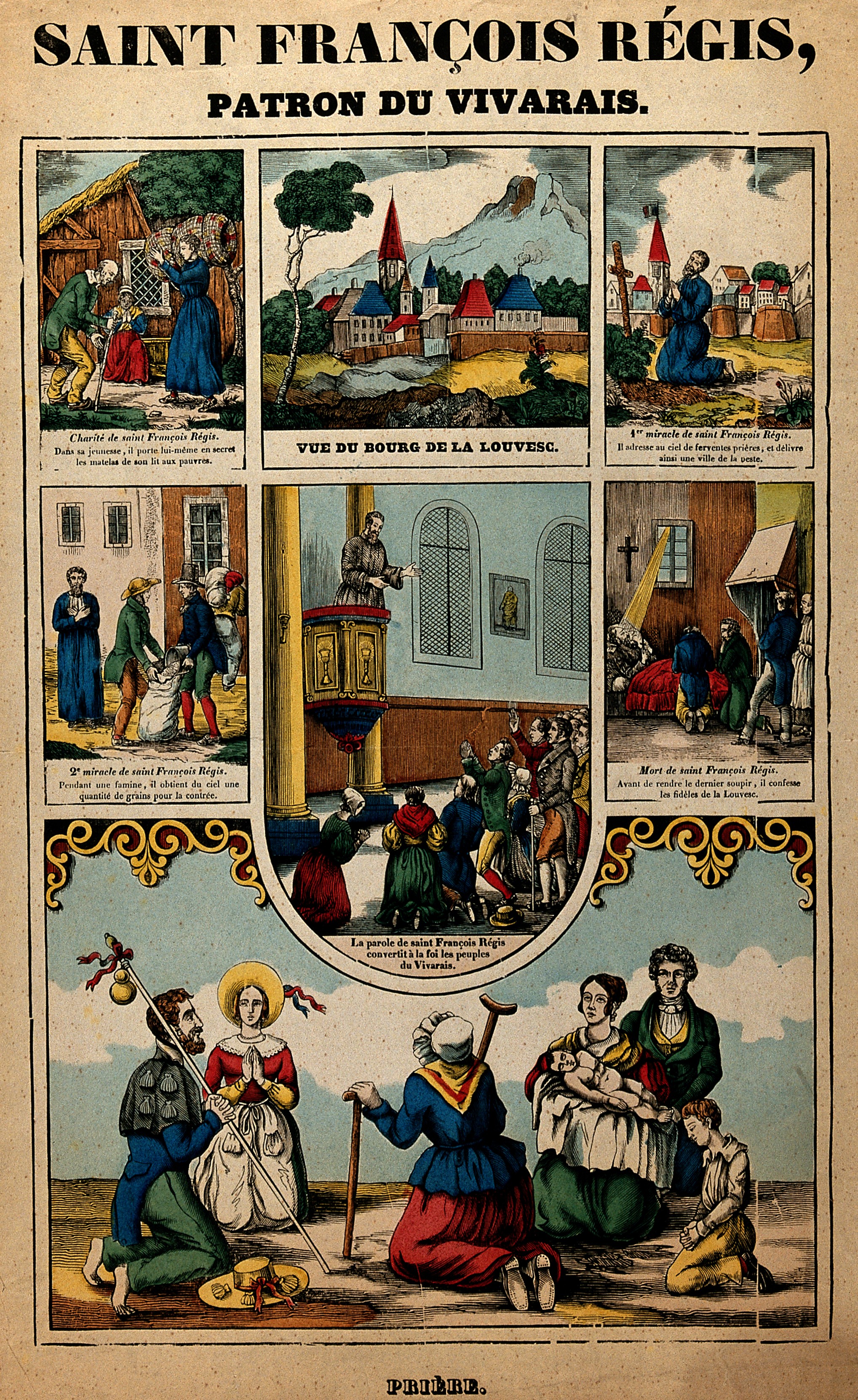

A French popular lithograph of Saint François Régis. (Image from the Wellcome Trust via Wikipedia Commons.)

Lacemakers’ songs from the Velay share some of the characteristics of those discussed in our post on ‘Sir Hugh’ and ‘Long Lankin’. There is a marked taste for long narrative songs, often with rather grisly content. In addition, in the Velay religious songs make up a substantial proportion of lacemakers’ repertoire. However, the song in this video is a bit cheerier, even though we only get to hear the first verse and the chorus. We provide the text of the full song below and a (rough) translation:

| Sur mon carreau, je fais de la dentelle, Dés le matin jusqu’à la fin du jour. De mon carreau, la garniture est belle; Rubans, velours le bordent tout autour. Petit fuseau, Babille, Sautille Petit fuseau: Autour de mon carreau.Sur le devant, sous une blanche écaille, De Saint Régis, on peut voir le portrait; C’est grâce à lui, dit-on, que je travaille, Sous d’autres saints le pourtour disparaît. Tous les fuseaux, comme des militaires, Et, vrais pantins pendus à leur ficelle, C’est tout autour d’une roue à fortune, De ses deux mains, l’agile dentellière Mais que ce soit du lin ou de la laine, Et l’on obtient guipure ou valenciennes, Avec les mains, la langue, aussi, travaille, |

On my pillow I make lace From morning till the end of the day. The decoration of my pillow is beautiful; It is bordered on all sides by ribbons and velvet. Little bobbin chatter, skip Little bobbin Around my pillow.On the front, under a white slip You can see the portrait of Saint Régis; They say it’s thanks to him that I can work The surround disappears under other saints. All the bobbins, like soldiers,

And just like puppets on a string,

It’s all around a wheel of fortune With her two hands the agile lacemaker Whether it’s of linen or wool And thus one obtains guipure or valenciennes While the hands work, so does the tongue, |

The words were composed sometime before 1904 by ‘A. de la Demi-Aune’ (a demi-aune is a measure 60 centimetres in length used for lace), the pseudonym of Hippolyte Achard (born 1842), one of the leading lace manufacturers of Le Puy: a manuscript memoir of his life and the lace business is preserved in the Municipal Library of the city. The music was by Marius Versepuy (1882-1972). At the beginning of the century Achard was very active in the defence of home-made (or to use the contemporary term, ‘true’ lace) against machine-made ‘false’ lace. Given the impossibility of competing on price, manufacturers and patrons emphasized the moral virtues of home-made lace, which kept women at home, under the eyes of the Catholic Church (even though Achard himself was somewhat anticlerical in his politics) while looking after their children, in comparison to the urban depravity and promiscuity that faced women moving into the factories. Thus home-made lace repelled the twin fears of rural depopulation and racial degeneracy. These themes are lightly invoked in the song.

Essentially, then, this is a propaganda piece. Yet it quite rapidly spread among lacemakers themselves, so that even by the First World War its origins had been forgotten and it became part of lacemakers’ repertoire. Perhaps the reason is that it was clearly by someone who knew the trade. Lacemakers in the Velay did decorate their pillows with images of saints, especially the patron saint of the Le Puy lace industry, Saint François Régis; the design was pinned to a roller; réseau is the word used for net… But in addition it articulates something which is often denied by historians of labour to such women — isolated in their homes and working at piece-rates — which is a sense of a collective, occupational identity and pride in their craft.

Further reading:

Hippolyte Achard, ‘La Dentelle du Puy pendant un demi-siècle, 1842-1892’, manuscript 130 res., Bibliothèque municipale du Puy-en-Velay.

‘Les Fuseaux!’ Chanson vellavo, paroles de Hippolyte Achard, musique de Marius Versepuy (Paris: Heugel, 1907).

Victor-Eugène Ardouin-Dumazet, Voyage en France 34: Velay — Bas Vivarais — Gévaudan (Paris: Berger-Levrault, 1904), pp. 63-4.

Georges Dubouchet, Les fées aux doigts magiques. Au pays de la ‘Reine des Montagnes’ (Saint-Didier-en-Velay; Musée de Saint-Didier-en-Velay, 2010).

David Hopkin, Voices of the People in Nineteenth-Century France (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), chap. 6: ‘The Visionary World of the Vellave Lacemaker’.

Louis Lavastre, Dentellières et dentelles du Puy. Thèse pour le doctorat, soutenue devant la faculté de droit de l’université de Paris, 8 juin 1911, (Le Puy: Peyriller, Rouchon et Gamon, 1911.

John F. Sweets, ‘The Lacemakers of Le Puy in the Nineteenth Century’, in Daryl M. Hafter, European Women and Preindustrial Craft (Bloomington IN: Indiana University Press, 1995).