Rosamond Lehmann was born in 1901 at Bourne End in Buckinghamshire, on the southern fringe of the lacemaking districts. Her father, Rudolph Lehmann, had been editor of Punch and, briefly, liberal MP for Harborough. The Lehmanns, originally from Germany, were an artistic dynasty: two of Rosamond’s great-uncles were painters, an aunt was a composer, one sister became an actress and her brother was editor of the influential periodical New Writing. The Curtis family, protagonists of her third novel Invitation to the Waltz (1932), are of a rather different background, a settled rural manufacturing dynasty whose fortune derives from paper mills. Nonetheless, Lehmann modelled this fictional household on her own. The lead character, Olivia Curtis, is a portrait of the novelist as a young woman, indicated by her frequent flights of imagination. The novel is set in 1920, and opens on Olivia’s seventeenth birthday; it relates her anticipation of, and then participation in, the dance held by the local gentry family, the Spencers.

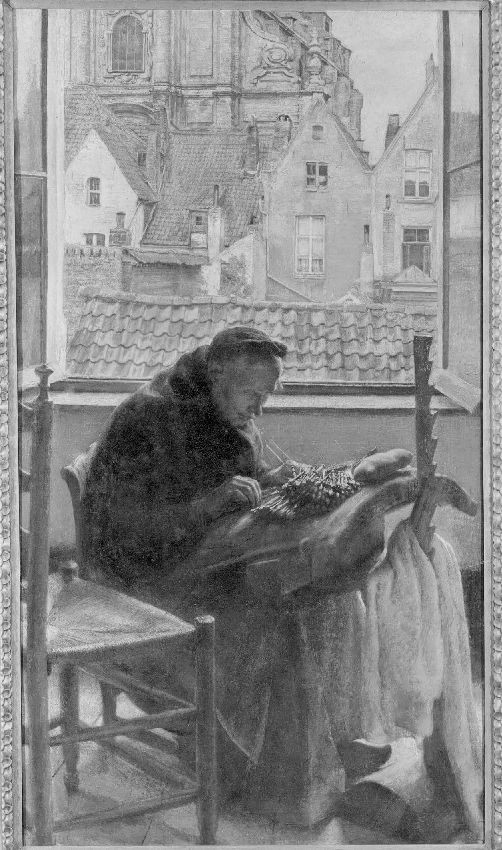

Bucks Lace Collar (Image provided by David Hopkin)

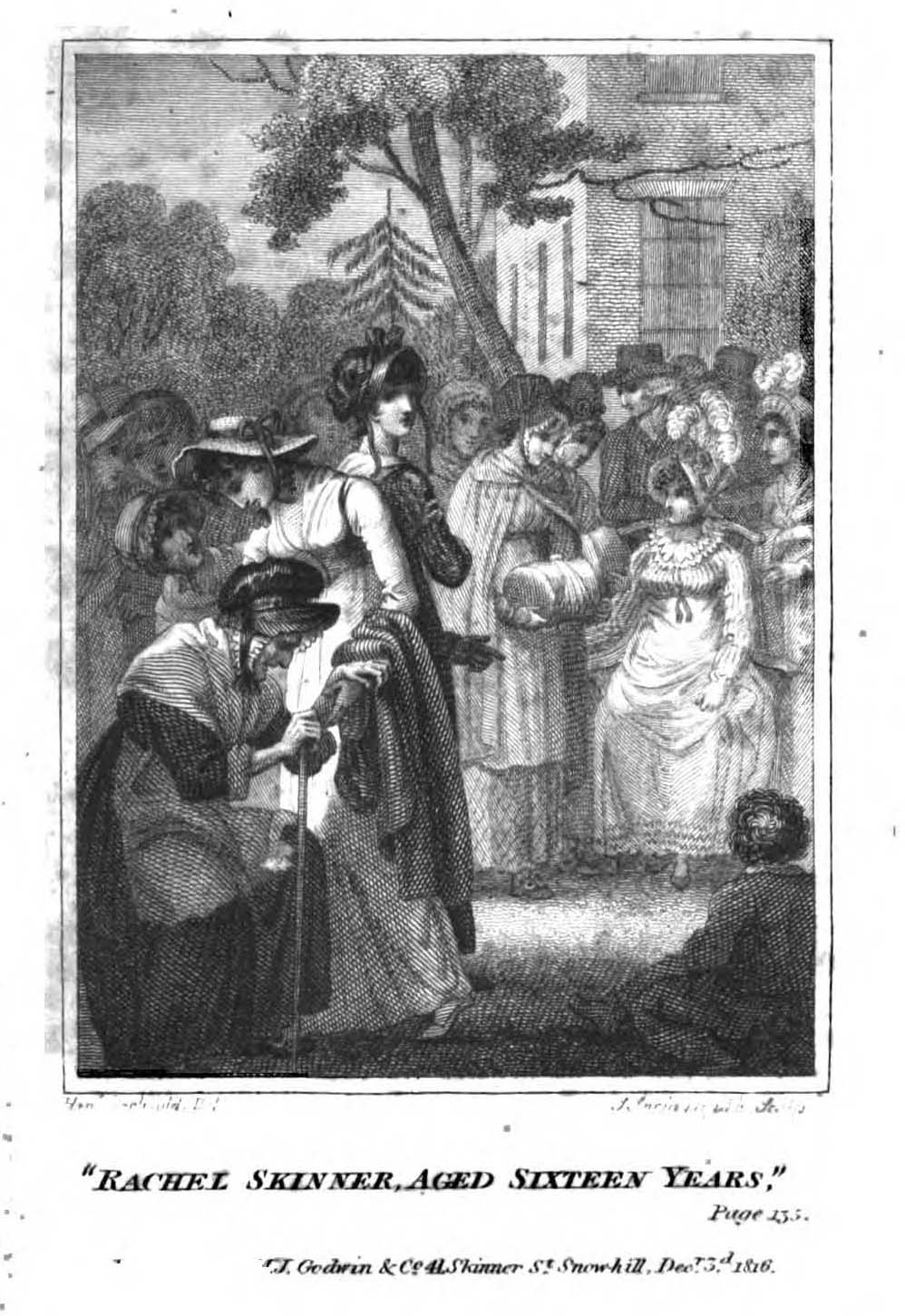

The Curtises know the Spencers but are not intimate with them. They are separated by fine but significant class distinctions: for instance Olivia and her older sister Kate do not ride, they cannot be ‘county’. Attracted and intimidated by the manners of the upper classes, Olivia experiences trepidation, embarrassment but also an occasional intimacy in her contacts with her social superiors. She is also sensitive to the barriers that separate her from the labouring population of the village. The first part of the novel consists of various encounters in which class distinctions are performed – with the dressmaker Miss Robinson, with the impertinent children of the sweep, and with the household servants. Olivia cannot readily assume the character of superiority that she knows is expected of her. Her awkwardness can develop into fear, even hatred. A tacit element in this antagonism is potential rivalry for the attentions of men, given the decimation caused by the War. These tensions underlie her interview with the lace girl.

Fashion and dress play a large part in the novel. They are the means by which Olivia and Kate establish their independent identities (though in the case of Olivia, her vision for herself is only partially fulfilled). But when it comes to lace, Olivia is forced to renounce her individuality, symbolized by her own plans for her ten bob birthday present, and assume a social role. Lehmann paints a plausible portrait of lace-selling at the tail-end of the handmade lace industry, when even the philanthropic lace associations were becoming moribund. However, her lace girl has imbibed many of those associations’ ideas about the values implicit in lace. She is careful to distinguish her products as ‘real lace’, as opposed to the machine-made alternative one might buy at Evans for a tenth of the price. She appeals to Olivia’s connoisseurship, or rather the connoisseurship that a real lady should possess, but Olivia does not. She attempts to establish a personal relationship with the Curtises, who as local notables and employers really ought to patronize the lace industry. She invokes the family values of domestic manufacture through her ability to support and comfort her invalid mother. Yet all the time one is aware that the lace-girl is relying on the philanthropy of the well-to-do. Almost in passing she mentions her hardships, her misfortunes: Olivia is obliged to part with her ten shillings, and she bitterly resents it. However, middle class status has its compensations as well as its responsibilities. The scene ends with Olivia expecting a (servant cooked and laid) meal: the matchstick legs of the lace-girl suggest she may not be getting any lunch.

Further Reading:

Rosamond Lehmann, Invitation to the Waltz. First published by Chatto & Windus Ltd in 1932.

Shusha Guppy, ‘Interview with Rosamond Lehmann: The Art of Fiction No. 88’, The Paris Review 98 (1985).

Vike Plock, ‘“I just took it straight from Vogue”: Fashion, Femininity, and Literary Modernity in Rosamond Lehmann’s Invitation to the Waltz’, Modern Fiction Studies 59:1 (2013).

Extract:

[It is the morning of Olivia’s seventeenth birthday. She has just returned home after visiting the dressmaker in Little Compton, when she encounters the maidservant Violet in the hall.]

‘Please, Miss Livia, there’s a young person to see you.’

‘To see me?’

‘Well, she wanted the one or the other of you. Madam’s out and I couldn’t find Miss Kate. So she said she’d wait.’

‘Is it one of the Miss Martins?’

‘Oh no, it’s a young person. Carries a case. I don’t know what she’s come after. I showed her into the servants’ ‘all. Will you see her?’

‘Yes, I suppose so.’ How queer.

Violet disappeared, returned, said coldly: Come this way please; and grudgingly made way for a short slight girl of about twenty, dressed neatly and shabbily in a fawn hat and coat, and carrying a suit-case.

‘Good morning’, she said. Her voice and smile anticipated antagonism.

She was a rather pretty anaemically pink-and-white girl with small regular features, blue circles round her eyes, and an appealing air of goodness.

Olivia said nervously:

‘Do sit down.’

She sat on the edge of a chair, laid her case down, and spoke in a modest and genteel voice.

‘I’ve brought a few things to show you – some of my work – thinking you might be interested. Are you interested in lace? – handmade?’ She smiled brightly.

‘I’m afraid I’m… I don’t know anything about it.’ Olivia’s heart sank. She blushed deeply.

‘Well, if I might just unpack my case. Real lace is so nice, I think, don’t you? It looks nice on anything. And of course it’s quite a rarity these days.’

She knelt on the floor, opened her case, and began to rustle about swiftly, with tiny narrow hands, among sheets of tissue-paper.

Now was the moment to say it was no good, that one didn’t want any lace, had no money with which to buy it. Oh, cruel fate! Any other day that would have been true. To-day Uncle Oswald’s ten-shilling note seemed to crackle audibly in her pocket, refusing for its late master’s sake to be denied.

Now was the moment to enquire searchingly into her credentials. She feebly ventured:

‘Did you make it yourself?’

‘Oh yes all myself,’ said the girl softly, lightly. Clearly she was gaining confidence. Not often could she have had such an auspicious start. ‘You see, I have my mother to keep. She’s a total invalid, of course – paralysed; so not being able to go out to work I took up lace-making. This is my biggest piece – a bedspread.’ She unfolded it, held it up in both arms. ‘It took me six months, this did.’

‘Did it really?’

And instead of coldly glancing before handing it back, one found oneself examining it, murmuring sympathetically:

‘Doesn’t it tire your eyes?’

‘Oh yes, they get ever so strained. That’s the worst of it. My eyes aren’t strong, and if they were to give out, well, I don’t know where we’d be.’ She gave another bright smile. ‘Of course I have my regular customers, but his time of year I go round and try to earn a bit extra, just to get Mother some little comforts for Christmas. It’s for her I do it. It isn’t very nice really to have to go round – you know what I mean. You feel you come at an awkward time and – it’s ever such a drag and –‘

‘Yes, it must be.’ Picture of door after door being shut in her face by haughty parlour-maids. ‘How awful for your mother.’

‘Yes, and she’s ever so patient – never a grumble. This is a little tea-cloth. You can’t have too many tea-cloths, can you? A table set – centre-piece and six mats. These little mats are all the rage now, aren’t they? — so much daintier than a tablecloth. A nightdress case. Some little traycloths – they’re nice. A set of doylies…’

‘They’re beautiful… But I’m rather afraid they wouldn’t be quite what I… not very much use…’

‘Not for Christmas presents? She was gently surprised.

‘Well, yes, of course. Only, as a matter of fact I haven’t really started to think about Christmas yet.’

‘Hadn’t you? I always think with Christmas shopping it’s best to get it done in good time, don’t you? Then it’s off your mind.’

The case was nearly empty now. Olivia said suddenly, with a show of firmness:

‘I believe it would be best if you could call again later – after lunch, perhaps – when my mother’ll be in. I’ll tell her. I’m sure she’d like to… She’d know better than me.’

‘I’m afraid I couldn’t do that.’ Her voice was gentle but decided. ‘I’ve a long way to go.’

‘Yes, I suppose you have.’

She saw through that all right.

‘Oh, this insertion will interest you. For trimming underwear. In different widths. Ladies always like my insertion. It’s strong, yet dainty.’

‘I don’t wear lace on my underclothes, I’m afraid.’

‘No – really?’ She raised her eyebrows, politely shocked, incredulous.

‘No, I don’t like it.’

Firmer and firmer. Silence fell.

‘A little collar.’ She took the last package from the case and placed it upon a chair; with hesitation, with a sudden collapse of assurance.

Silence again. She knelt on the floor among a litter of white paper, lace and linen, her hands loosely folded in her lap, her head drooping. Then slowly she started to fold up the bedspread, then the teacloth, the centre-piece, to smooth out the tissue-paper, to put everything back in the old suit-case; with meek gestures, with silent disappointment folding up, laying away her unwanted handiwork.

It was too much. Olivia picked up the collar.

‘This is very pretty.’

The girl glanced up.

‘Yes, it’s a nice little collar. It’s so uncommon.’ She went on packing.

‘I think I’d like… It would be so useful. How much is it?’

She paused, then said:

‘It’s fifteen and six, that one.’

‘Fifteen and six! Oh, I’m afraid I can’t then – I’ve only got ten shillings – at the moment.’

And quickly, for fear of being suspected again, she drew her purse from her pocket, opened it under the girl’s nose, and extracted its sole contents – the ten-shilling note.

‘There’s a lot of work in this collar. You can see for yourself.’

‘I know.’ Hope sprang up again. The miserable offer was to be rejected. ‘I’m so sorry. I can’t…’

The girl continued reflectively:

‘Still – I might make you a special price – as you’re a new customer. I’ll let it go for ten shillings.’

‘Oh, will you? Well thank you very much. That’s splendid.’

The girl took the note, put it in a large black handbag, thanked her politely, without warmth, and went on packing. Suddenly she said with decision:

‘I’d have liked you to have had the tea-cloth. You’d pay double the price for it in any shop.’

‘No, thank you, I couldn’t. I’m afraid I must go now.’

Too late, she felt all the necessary resolution.

The girl closed and strapped the suit-case, got up, lifted it with a slight effort.

‘I hope it’s not too heavy for you.’

‘It is a bit heavy.’

And perhaps no lighter by the end of the day… Dragging herself home late at night… A weak voice from the pillow, whispering anxiously: ‘Well?… Brokenly answering: Only one collar…

‘Come out this way.’

She opened the front door. They smiled faintly at one another. The girl said with restraint:

‘Thank you very much.’

‘I do hope you’ll be able to get plenty of – of comforts for your mother.’

‘Yes. Thank you.’

Whatever they were, surely ten shillings would buy a certain amount of them.

‘Good-bye.’

‘Good morning.’

She went down the steps and along the drive, hobbling on irritating matchstick legs, one puny shoulder pulled down by the weight of the suit-case.’

[… A little while later Olivia shows her purchase to her older sister Kate.]

‘Like to see what I’ve bought with my ten bob?’ cried Olivia; and she flung down the collar upon the table.

‘Good Lord, what’s that?’ Kate held it up by one corner.

‘Isn’t it pretty?’

‘Where on earth —?’

There was nothing for it but to tell the whole story.

‘Lumme!’ said Kate. ‘So that’s what that foul Violet came flouncing up here for. I hid.’

She spread the collar out upon the table and was silent, examining it.

‘Don’t you think it’s rather nice?’

It was looking its worst somehow: exactly as if it ought to be thrown on the fire.

‘How much did she rook you?’

‘Ten bob.’

‘The whole lot?’

‘Yes. She reduced it for me.’

After a pause, Kate said:

‘What’ll you do with it?’

‘Oh, put it on some frock, I suppose. It’s bound to come in somehow. Real lace always does.’

Faintly Kate’s nostrils dilated, but she said nothing. This was more bad luck than downright folly, and she could sympathize. Yet Olivia felt her pretences snatched away, Kate’s finger pointing the way inexorably to surrender, to truth. She said suddenly:

‘Don’t tell Mother.’

‘Of course not.’

‘Bang goes my whole income.’

Kate nodded, murmured:

‘Sickening.’

‘I’ll give it to Nannie for Christmas. She’ll love it.’ She giggled, blinked back a tear. ‘Little will she guess what I’ve spent on her. She’ll think it came from Evans, one and eleven three.’

‘Perhaps it does,’ said Kate, busy with paper and pins.

‘Don’t be absurd. It’s handmade. You can see it is… Can’t you?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Well, how does one tell?…’

All supports cracked together. She threw up her hands, fell.

‘Do you think –’ Kate spoke with unwonted hesitation – ‘she can have been – could it have been a swizz?’

‘Of course not. She was awfully sort of superior. And all that about her mother. She couldn’t have made that up.’

‘I suppose not,’ agreed Kate, starting to cut out.

Olivia sat down and meditated upon the transaction. I never disliked any one so much, she thought. The worst was the lack of gratitude. Ten shillings snatched by compulsion, stuffed into her black bag, sitting there quiet and avid as a spider, then asking for more… asking for more. No, she was not pathetic. She was sinister.

She picked up the collar and threw it into the corner.

‘It’s not as bad as that,’ said Kate.

Olivia yawned.

‘Lord, I’m hungry! It’s been a full morning.’