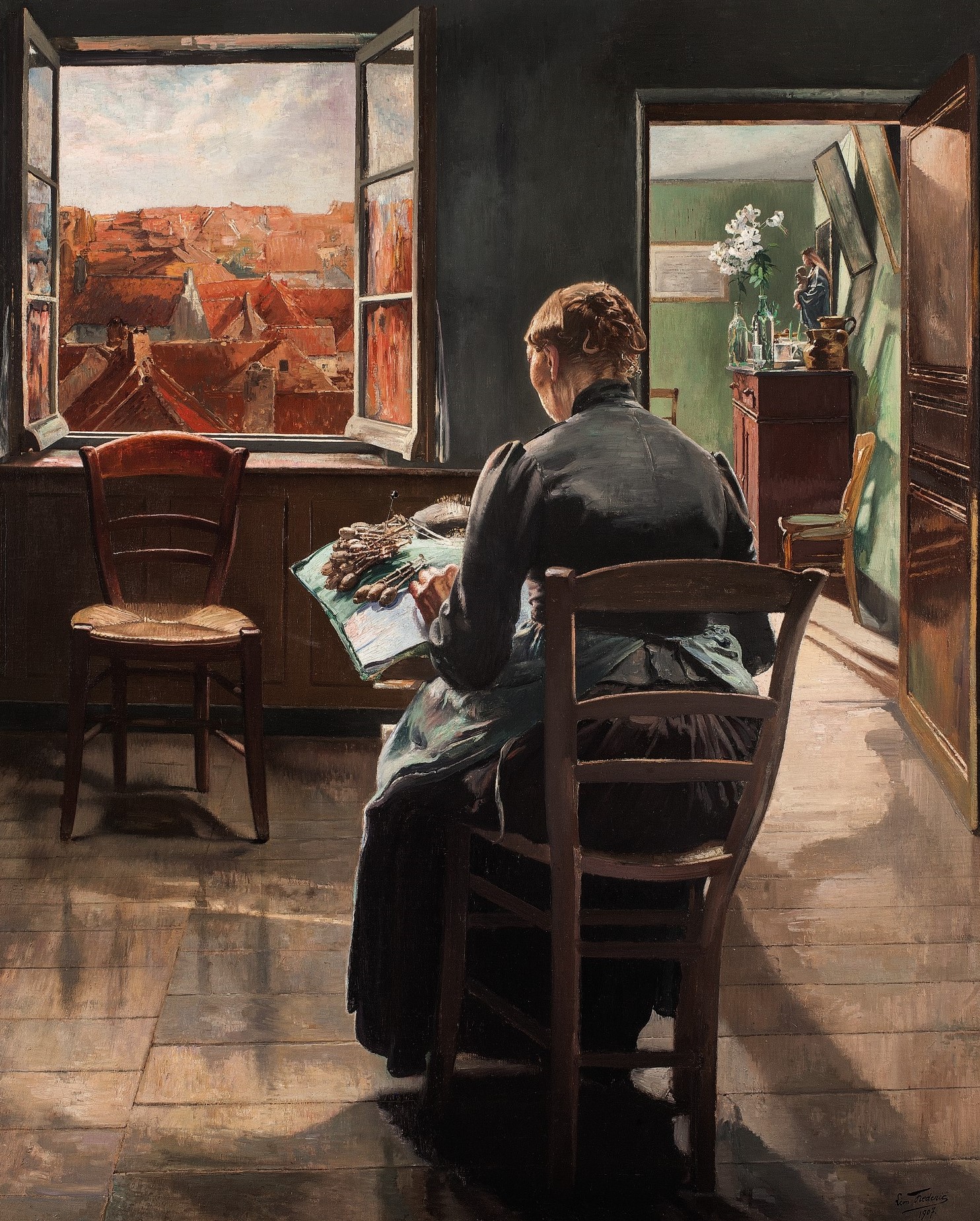

Léon Frédéric (1856-1940), ‘The Flemish Lacemaker’, 1907.

A post for a rather depressing winter. Some Flemish literature is written in Dutch, and some is, or at least was, written in French. Despite his name, Camille Lemonnier (1844-1913) identified as Flemish; yet, as was true of most of the Belgian upper classes at the time, his chosen mode of expression was French. At the turn of the twentieth-century he was probably Belgium’s most famous author, and the most notorious in the country after his appearances before the courts for literary offences against public morality. He was compared to Émile Zola not just for his social realism (or ‘naturalism’ as people termed Zola’s school) but also for his unabashed explorations of sexual desire, religious fervour and mental breakdown. He was as frequently coupled with the French decadent writer Joris-Karl Huysmans. In fact, Lemonnier embraced several literary fashions in turn, including symbolism. But if one had to pigeon-hole him, perhaps one could locate him in the distinct Flemish school of turn-of-the-century ‘mystic realism’ which also includes Georges Rodenbach (1855-1898) and Émile Verhaeren (1855-1916).

Alfred Stevens (1823-1906), ‘Camille Lemonnier in the artist’s studio’, c. 1900. Fondation Roi Baudoin, courtesy of Wikipedia Commons. Lemonnier was a great promoter of Belgian painters.

Lacemakers do not feature often in Lemonnier’s fiction, nor even in his non-fiction guides to his native country. The one exception is his prose-poem ‘La jeune fille à la fenêtre’, which appeared in the Parisian radical literary review Gil Blas in January 1892. The setting is Bruges – the ‘dead city’ of Rodenbach’s Bruges-la-Morte, a crumbling labyrinth of medieval relics, dissolving into the waters of its silent canals. Here the past, with its vanished promises and enduring regrets, weighs so heavily on the present that it crushes all life, all hope. The population’s only motive force is the monotonous repetition of Catholic rituals.

Karel Boom (1858-1939), ‘The Lacemaker’. Medievalism was one facet of the symbolist movement, in art as well as literature.

The heroine of Lemonnier’s poem is a young lacemaker who we observe alternately working on her pillow or pensively watching evening fall across the city. Although the precise nature of her heartache is not specified, it is clear that she has loved and lost. She is working on a bridal veil she will never wear. The bridal veil is a common theme in the literature of lacemaking, harking back to the legends of the origins of lace, whether located in Venice (another aqueous ‘dead city’) or Flanders. Only one year before, in 1891, a younger albeit more traditional French poet, Charles Fuster (1866-1929), had told a very similar story in his poem ‘La dentellière de Bruges’. Fuster’s lacemaker is employed by very person on whom she has set her heart to make a veil for his bride: she dies, of consumption, just as she completes the task, and her lace instead serves as her shroud in a ‘wedding of the dead’ (a custom we have discussed in a previous blog). It seems likely that Lemonnier knew Fuster’s poem not least because it was regularly performed on the stage as a dramatic monologue.

Henri Le Sidaner (1862-1939), ‘ A Canal in Bruges at Dusk’, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Le Sidaner’s crepuscular townscapes capture some of the symbolist enthusiasm for the ‘dead city’. Courtesy of ArtUK.

Death approaches Lemonnier’s lacemaker too, though the source of the danger is less clear. The young working-class woman whose life-chances are cut short was a stock character of nineteenth-century literature – think of the Parisian seamstress Mimi in La Bohème. But whereas social realists fulminated against the economic and sexual exploitation that caused these tragedies, symbolists luxuriated in their aesthetic possibilites, just as they relished the spectacle of the dead city (Rodenbach even campaigned against any modernisation of Bruges). The church viewed through the lacemaker’s window is, as we have seen before in another blog post, a commonplace of nineteenth-century visual art. But for the symbolist poet the exterior world is a projection of the protagonist’s interior, explicitly so in this poem where the young lacemaker’s heart is also a chapel, the mirror of the one she can see across the canal, and inhabited by the same sad and desperate characters who come to plead with the plaster saints. Women’s suffering, infused into the making of lace, heightened the value of the lacemakers’ art for these fin-de-siècle writers.

Firmin Baes (1874-1943), ‘The Lacemaker’s Dream’.

Like Fuster’s poem, Lemonnier’s was also meant for the stage: the first performance of the monologue was given by Marguerite Rolland at the Salon des XX, an art exhibition, in Brussels in 1892. Later it was set to music by the Belgian composer Eugène Samuel (1862-1942, better known as Samuel-Holeman after he added his dead wife’s name to his own in 1905), first as a simple piano accompaniment in 1903, then for an ensemble in 1906. The piece remained quite popular both in Belgium and France through the first three decades of the twentieth century, but it has only been recorded once, in 2019, by the mezzo-soprano Pauline Claes, accompanied by Mathias Lecomte on piano and the Sturm und Klang ensemble.

The composer Eugène Samuel-Holeman, 1922.

Despite his fin-de-siècle celebrity, very little of Lemonnier’s work has been translated into English. The translation offered below is our own, and we make no claims for its poetic qualities. It is based on the version of the poem published in Lemonnier’s 1898 collection La petite femme de la mer. The text utilized by Samuel-Holeman was a little different (and a translation of that is provided in the booklet accompanying the Sturm und Klang cd).

LA JEUNE FILLE A LA FENÈTRE (THE YOUNG GIRL AT THE WINDOW) BY CAMILLE LEMONNIER.

| Par l’entre-bâillure des mousselines, à travers la vitre comme étamée d’un soir d’hiver, un canal s’aperçoit. De l’autre côté du canal, les maisons sont bordées par un quai. Une vieille arche de point, un peu au delà vers la gauche, érige un crucifix. Il neige. Dans la reculée, un chevet d’église s’ecorne, cassé par la perspective.

LA JEUNE FILLE A LA FENÈTRE, faisant de la dentelle. Mes mains, mes petites mains, mes pâles mains jamais nuptiales, les avez-vous fait danser toute cette après-midi, les fuseaux!…. C’est ma triste vie qui, fil à fil, s’enroule autour des épingles d’or, et les fils sortent de mon coeur, les fils vont de mon coeur à mes doigts, les beaux fils couleur de neige qui retiennent mon coeur captif. Mes soeurs, s’il ne vient pas, Celui que j’attends, vous enlèverez les épingles, vous détacherez la dentelle, vous l’éploierez sur la nuit de mes yeux… Je l’ai commencée avec les fils de mai… Il neigeait alors de l’aubépine, les soirs avaient des tuniques blanches de petites filles; dans l’église, les orgues du mois de Marie chantaient. Et mon coeur aussi était une église où, derrière les vitraux sous la petite lampe, mon Jésus resplendissait. Son sourire me regardait avec la forme de mon propre coeur; et je lavais doucement ses plaies avec des larmes qui n’avaient pas encore pris le goût du sel! Mes mains, mes joyeuses mains jamais lasses, c’était mon voile de mariée qu’en ce temps vous fleurissiez de marguerites et d’étoiles… Le prêtre a quitté la chapelle; l’enfant de choeur a éteint les cierges de l’autel; les orgues se sont tues dans les soirs. L’hiver était venu; et j’ai continué mon beau voile avec des fils de neige. Mes mains ont filé la neige qui tombait dans l’hiver de mon coeur, elles en ont fait le fil avec lequel maintenant s’achève le triste voile. Mon coeur est une église où, après la messe, il passe des visages aux yeux vides comme des chambres de trépassés. Des mères intercèdent à genoux pour leur enfant malade. Une très vieille jeune fille porte son coeur dans ses doigts et l’offre aux Saintes miséricordes. Je suis cette mère, Seigneur, intercédant pour mon amour malade, je suis cette vieille jeune fille, Seigneur! Je remets entre vos mains l’offrande douloureuse de mon coeur inexaucé. Dévidez-vous, les fuseaux! Mes larmes à la longue ont durci de leurs cristaux le fil; la dentelle sous mes larmes s’est gelée en dures et brillantes fleurs de givre. Dites, dites, mes soeurs, le voile, en l’éployant, sera-t-il pas assez long pour s’étendre de mon visage à mon coeur? (Les cloches sonnent à l’église. Elle regarde s’allumer les vitraux dans le choeur. Des mantes noires passent sur le pont.) Je les reconnais: ce sont toujours, depuis que je travaille à cette fenêtre, les mêmes visages de soir et de prières; l’hiver aussi a neigé sur ces âmes. Mes espoirs, vous vous êtres usés comme les genoux qu’elles vont fléchir devant les autels… Chaques soir, elles passent au tintement de la cloche dans leurs grands manteaux; elles se signent devant le crucifix; elles vont vers les cierges et les chants, comme des oiseaux battant de l’aile du côté des volières. Mon coeur, comme elles, porte une sombre mante… Mon coeur passe sur un pont, mon coeur va vers une chapelle dont le prêtre est mort il y a longtemps. Nulle lampe ne brûle plus par delà les verrières, nul encens ne fume plus sous les voûtes; et cependant mon Jésus y est couché parmi l’or et les aromates. Silence! Mon coeur a frappé à la porte; la porte ne s’est pas ouverte, la porte jamais ne s’ouvrira. Ah! sonnez, les cloches! sonnez, mes glas! Mes prières connaissent une chapelle muette comme un tombeau. (Elle a laissé retomber les bobines et rêve, les yeux distraits, perdus dans la neige qui floconne lentement.) Nous étions alors autour de la table quatre petites soeurs. Une est partie, un soir qu’il neigeait comme à présent; elle n’avait pas quinze ans. Celle-là sans doute, dès le berceau, avait été fiancée à un beau jeune homme pâle dans la lune… Et ensuite, la table est devenue trop grande pour les trois autres. Annie! ma chère Annie, pourquoi ne suis-je pas couchée à votre place dans la petite bière où vos lys ont fleuri pour l’éternité? J’étais l’aînée de nous; il n’eùt fallu qu’un peu plus de bois au cercueil… Et tant qu’elles furent quatre, les soirs, dans le jardin, les petites soeurs dansaient une ronde en chantant: “Il était un beau prince, et ri et ri, petit rigodon…” Ah! je ne veux plus chanter cela. Une princesse au fond d’une tour espère la venue du beau prince… Le beau prince a passé par le pays; il a passé devant la tour; la petite princesse est morte de chagrin parce que le beau prince n’a pas trouvé la clef de la tour… Annie, ma chère Annie, est-ce-que quand il neige, ce ne sont pas les pleurs gelés des pâles jeunes filles qui tombent des étoiles – des pauvres jeunes filles pleurant le bel amant qui n’est pas venu? Dites, bonne Annie, est-ce que ce n’est pas la charpie que des petites mains de jeunes filles effilent au fond des étoiles pour panser les blessures de celles qui sont demeurées? (Une lampe s’allume dans une des maisons en face.) La bonne dame tout à l’heure descendra son chien à la rue, elle le regardera un instant courir dans la neige; ensuite elle le rappellera. Et, à travers la mince guipure blanche, je verrai la bonne dame passer l’eau sur son thé, ajouter quelques points à sa tapisserie… (Ah! toujours la même depuis de si longues années!)… puis s’endormir, son petit chien sur ses genoux: ils n’ont pas connu le poids léger d’une chair d’enfant. (D’autres fenêtres s’allument.) Ah! Des lampes encore! Des lampes comme des yeux rouges de pleurs! Des lampes comme des regards d’aveugles derrière la vitre d’un hôpital! De vieilles gens sans doute, des âmes lasses d’infinies résignations! D’anciennes douleurs de jeunes filles regardant neiger le silence à travers le cloître de leur coeur. “Il était un beau prince! Et ri et ri, petit rigodon!” Pourquoi la triste chanson me revient-elle surtout ce soir? Pourquoi grelotte-t-elle à la porte comme un vieux pauvre chargé des reliques d’un autre âge? Il y a si longtemps qu’elle est morte, la princesse: le beau prince sans doute n’en a jamais rien su… Mes mains, séchez les pleurs de mes yeux. (Sur le pont tout à coup quelqu’un apparaît, un homme don’t on n’aperçoit pas le visage à travers la neige et la nuit. Il s’arrête près du crucifix et regarde du côté de la fenêtre. Elle rit.) Le voilà, mon prince Charmant… Il y a six ans qu’il passe sur le pont, tous les soirs, à la même heure. J’ignore son nom; je sais seulement qu’il a des cheveux blancs. Il passe, il regarde; nous ne nous sommes jamais rien dit. Mes soeurs l’appellent: l’ange des dernières pensées du jour. Et ensuite ce n’est plus qu’une ombre au bout de ce canal… Il s’en ira dans un instant comme il s’en est allé tous les autres soirs. Ah! qui aurait dit, quand nous étions quatres petites soeurs chantant cette antique ballade, qu’un si vieux monsieur s’arrêterait devant ma tour et que je serais la princesse des espoirs qui ne doivent pas se réaliser! Je ne tiens plus au monde pourtant que par cette charité d’un regard qui se tourne vers ma vitre… (L’inconnu fait un geste et quitte le pont.) Parti! Et ce geste encore depuis six ans, ce geste dont toujours il semble se résigner et prendre à témoin le ciel de l’impossibilité de franchir la distance qui nous sépare… Il n’y a cependant là qu’une flaque d’eau, il n’y a que des silences d’un peu d’eau qui dort! Mon coeur est une maison au bord d’un canal, avec une fenêtre derrière laquelle veille mon amour et où se réfléchit le regret d’un passant. (La nuit est entièrement tombée; une douceur de sommeil pèse sur la ville. Là-bas, les hautes fenêtres de l’église se découpent, étincelantes.) Seigneur, je mêle ma voix à celles de vos humbles servantes… Seigneur, prenez en pitié ma longue peine… Donnez-moi la force de continuer jusqu’au bout ce voile de mariée, afin que, n’ayant pu servir à ma vie, il serve au moins à ma bonne mort… Et vous, mes mains, mes pauvres mains flétries, si, à force de vider les bobines, le fil venait à vous manquer, prenez les lins de mes cheveux, prenez à mes tempes les fils sur lesquels a neigé l’hiver. (Elle ferme les rideaux, allume sa lampe et se remet à sa dentelle.) |

A gap in the curtains reveals, through a window, frosted as on a winter’s evening, a canal. The houses on the other side border on a quay. To the left, the arch of an old bridge, and on it is erected a crucifix. It is snowing, in the distance the apse of a dilapidated church is visible, distorted by the perspective.

THE YOUNG GIRL AT THE WINDOW, making lace. My hands, my little hands, my pale hands, never a bride’s hands, you’ve kept the bobbins dancing all this afternoon!…. It’s my sad life that winds itself, thread by thread, around the golden pins, and the threads are drawn from my heart, the threads stretch from my heart to my fingers, the beautiful threads that hold my heart captive. My sisters, if he doesn’t come, the One who I’ve been waiting for, you must pull out the pins, you must detach the lace, and you must spread over my darkened eyes… I started it with the threads of May… It was snowing then with hawthorn blossom, the evenings were full of little girls in white dresses; in the church, the organs sang the Month of Mary. And my heart, too, was a church where, behind the stained-glass windows, under a little lamp, my Jesus was radiant. He smiled at me with the true form of my own heart; and I gently washed his wounds with tears that had not yet acquired the taste of salt! My hands, my joyous hands that are never tired, this was my bridal veil which, back then, you decorated with daisies and stars… The priest has left the chapel; the choirboy has extinguished the candles on the altar; the organs are silent in the evenings. Winter had come; and I still made my beautiful veil with snow-white threds. My hands spun the snow that fell in the winter of my heart, they first made the thread with which they now complete the sad veil. My heart is a church where, after mass, faces with blank eyes like the rooms of the dead pass by. Mothers plead for their sick child. An aged spinster carries her heart in her fingers and offers it to the merciful Saints. I am that mother, Lord, pleading for my sick love, I am that old spinster, Lord! I commit into your hands the sad offering of my unfulfilled heart. Empty the bobbins! My tears have long since hardened the thread into crystal; the lace has frozen under my tears into brilliant, callous frost flowers. Tell me, tell me, my sisters, will the veil, when it is spread out, be long enough to reach from face to my heart? (The church bells ring. She watches as the stained-glass windows light up in the choir. Cloaked figures cross the bridge.) I know them, they’re always the same, ever since I’ve worked at this window, the same evening faces, the same prayers: winter has fallen on these souls too. My hopes are as worn out as their knees inclined before the alters… Every evening they pass by covered by their large cloaks as the bells ring; they make the sign of the cross before the crucifix; they flock towards candles and hymns like birds flapping beside their aviaries. My heart crosses a bridge, my heart approaches a chapel where the priest died long ago. No lamp burns behind the windows, no incense drifts under the vaults; and yet my Jesus lies amidst gold and sweet-smelling herbs. Silence! My heart knocked on the door, the door did not open, the door will never open. Oh! ring out you bells! ring out my death knell! My prayers know a chapel as silent as the grave. (She lets the bobbins fall and dreams, her gaze distracted, lost in the snow falling slowly in flakes.) There used to be four of us, four little sisters around a table. One left, on an evening when it was snowing just like now; she wasn’t even fifteen. No doubt she had been, since she was in her cradle, afianced to a handsome young man as pale as the moon… And then the table became too big for the other three. Annie! my darling Annie, why am I not lying in your place in the little bier where your lilies flower for all eternity. I was the eldest; it would have only needed a little more wood for the coffin… When there four, in the evenings, in the garden, the little sisters danced a round singing “There was a handsome prince, tee hee, little rigodon…” Oh! I don’t want to sing that any more. A princess hidden in a tower hopes for the arrival of a handsome prince… The handsome prince passed close by; he passed right by the tower; the little princess died of heartache because the handsome prince did not discover the key to the tower… Annie, my darling Annie, when it snows, aren’t those the frozen tears of pale young girls falling from the stars – the poor young girls crying for the handsome lover who never came? Tell me, sweet Annie, isn’t it the little hands of young girls that spin the lint up there in the stars to bind the wounds of those who have been left behind? (A lamp lights up in the house opposite.) The good lady will soon come down with her dog into the street, she will watch him for a moment running around in the snow, then she’ll call him back. Then, through the thin lace curtain, I will see that good lady pour hot water on her tea, add a few stiches to her tapestry… (Ah! always the same one these long years!)… then she’ll fall asleep, her little dog on her knees: they have never known the light weight of a child. (Other windows light up.) Ah! More lamps! Lamps like eyes red with weeping! Lamps like the eyes of blind people behind hospital windows! Old people, no doubt, their souls worn out by countless renunciations. The timeworn sorrows of young girls watching the snow fall in silence through the cloister of their heart. “There was a handsome prince! Tee hee, little rigodon!’ Why does that sad song haunt me this evening? Why does it tremble at the door like an old beggar burdened with the relics of another age? She died so long ago, the princess: the handsome prince doubtless never knew anything about it… My hands, wipe away the tears from my eyes. (Suddenly someone appears on the bridge, a man whose face is indistinguishable through the snow and the gathering night. He stops by the crucifix and looks up at the window. She smiles.) There he is, my prince Charming… For six years he has crossed the bridge, every evening at the same time. I don’t know his name; I only know he has silver hair. He’s going past, he looks up; we’ve never exchanged a word. My sisters call him: the angel of the day’s last thoughts. And then he’s nothing more than a shadow at the end of the canal… He’ll be gone in a moment just as he does every other evening. Oh! who could have known, when we were four little sisters singing that outmoded ballad, that such an old gentleman would stop before my tower and that I would be the princess of hopes that can never be fulfilled! I am indifferent to the world except for the kindness of that glance up towards my window… (The unknown man makes a gesture and leaves the bridge.) Gone! And that same gesture all these six years past, a gesture that seems to say he is resigned and takes Heaven as his witness to the impossibility of surmounting the distance that separates us… Yet it’s nothing but a pool of water, there’s just silences and a little stretch of motionless water! My heart is a house by the edge of a canal, with a window behind which my love keeps watch and in which are reflected the regrets of a passer-by. (Night has fallen completely; a sweet sleep enfolds the town. Further away, the high windows of the church stand out, glittering.) O Lord, I entwine my voice with those of your humble servants… O Lord, take pity on my long suffering… Grant me the strength to finsh this wedding veil so that, never having served me in life, it will at least serve me in death… And you, my hands, my poor jaded hands, if after you’ve emptied the bobbins, you lack thread, takes threads from my hair, take from my temples the threads on which winter has snowed. (She closes the curtains, lights her lamp, and takes up her pillow again.) |

Leave a Reply