Eugène Laermans, ‘The Emigrants’ (1894). Musée des Beaux-Arts, Brussels. Migration was one of the consequences of the Flemish linen crisis of the 1840s.

In the nineteenth century there were lots of Catholic priests like Giovannino Guareschi’s fictional Don Camillo — opinionated, prejudiced and pugnacious, but also deeply committed to the welfare of their parishioners and devoted to their ‘little world’. They dominated their communities and examples of both their authoritarianism but also their humour have passed into folklore. The Flemish priest Constant Duvillers was one of their number. In Woubrechtegem, the tiny parish he was sent to in 1854 by the Bishop of Ghent (probably as punishment for his outspoken defence of the Flemish language), people still remembered him nearly 100 years after his death. Some of the stories that had become attached to him are standards of clerical folklore, such as his ability to compel thieves to return stolen goods. Others are perhaps more reflective of his personal eccentricities. Priests were obliged to read the Bishop’s annual Easter message from the pulpit: Duvillers, who disliked both the Bishop and long services, would announce ‘Beloved parishioners, it’s exactly the same as last year: those that can remember it, that’s good; those that cannot, that’s just as well too.’[1]

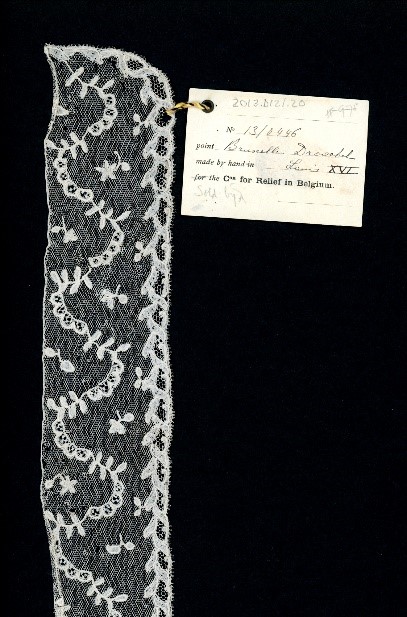

Constant Duvillers, priest of Middelburg in East Flanders

However, this post concerns his time at his first parish ― Middelburg ― where he served from 1836 to 1854. This village sits right on the corner where East and West Flanders meet the border with the Netherlands. It is in ‘Meetjesland’, a nickname for the region that Duvillers popularized through his annual Almanak van ‘t Meetjesland, which he published under the pseudonym ‘Meester Lieven’ from 1859 until his death. The story Duvillers told (and possibly invented) was that, when the locals learnt that the notorious womanizer Emperor Charles V was to travel through the region, they hid all the young women and only old women were visible, leading the Emperor to exclaim ‘This is little old lady land’ [Meetje is a colloquial term for ‘granny’].

The almanac, with its plain-speaking moralizing and practical advice, demonstrated Duvillers’ commitment to popular education and the promotion of the Flemish language. There was nothing he disliked more than a Fleming putting on French airs, or a ‘Fransquillon’ to use the pejorative term popularized in the 1830s, and the subject of a bad-tempered satirical poem by Duvillers, ‘De Fransquiljonnade’ (1842). For Duvillers and many other Flemish priests, French was the language of Robespierre, of irreligion and revolution. Inoculating the good Catholic Flemish population against this toxin required the provision of wholesome and comprehensible literature in their own language. Duvillers was responsible for a host of such small, cheap books, often pseudonymous, which, like his almanac, mixed the homely wisdom and folk humour of proverbs with overt moralizing and religious instruction.

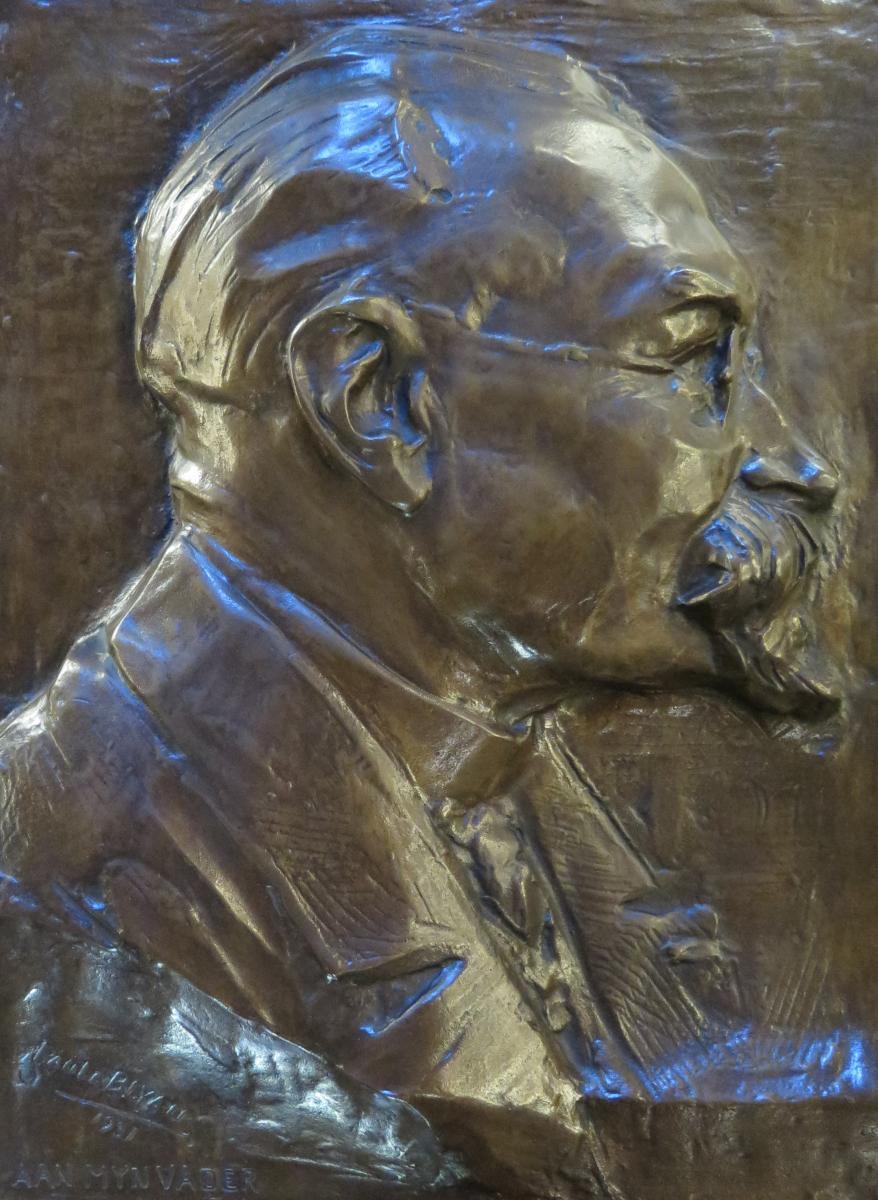

The proverb was one of Duvillers’ favourite genres, the song was another. Among his publications are three books of songs, the first of which (1844) was dedicated for the use of the Middleburg girls’ school: several of its twenty songs refer to lacemaking. In 1846 and 1847 there followed two more volumes containing fourteen and fifteen songs respectively, which were intended for use in the lace schools.

The background to these publications was the devastating crisis that affected Flanders principal industry, linen manufacturing, during the 1840s. In 1840 linen occupied nearly 300,000 people in Flanders, about twenty per cent of the population. They were employed in their own homes as spinners and weavers, supplementing their incomes by growing their own food on smallholdings. By the end of the decade this entire sector had all but disappeared. The causes included competition from British factory-produced linens and the displacement of linen by cotton, but this crisis in manufacturing was also exacerbated by poor harvests in the late 1840s, the same period as the Irish Potato Famine. Unemployment and high food prices coincided with typhus and cholera epidemics. For the fledgling Belgian state, born out of an earlier revolution in 1830, misery and starvation in Flanders presented a crisis of legitimacy. In other European countries the ‘Hungry Forties’ led to protest and even the overthrow of the political order. How could that outcome be avoided in Flanders too?[2]

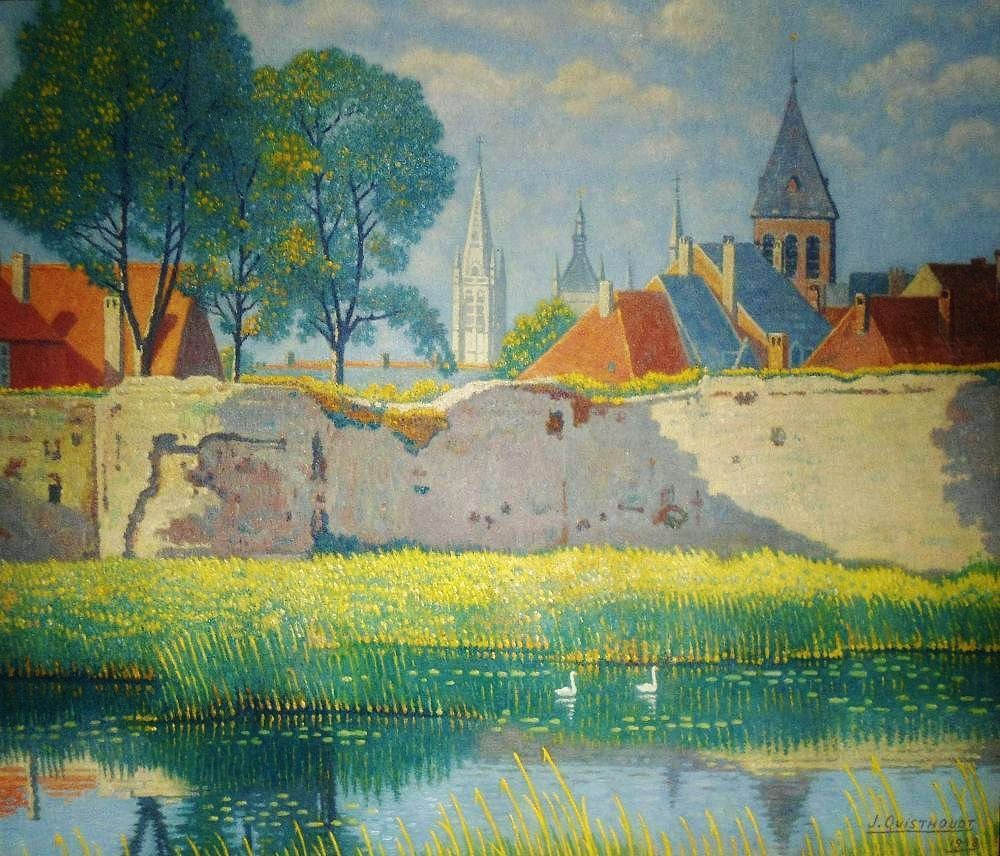

One answer was to retrain the population to make lace. This might seem an odd choice given that machine-made lace was already a source of competition for Flemish handmade lace. Nottingham and Calais tulle had effectively wiped out Lille’s lace industry in the 1830s. But the fashion for tulle had crashed, and the market for Flemish Valenciennes lace was sufficiently recovered for this project to make sense. Up until 1830 lacemaking had been a largely urban manufacture in Flanders, but in the 1840s it would desert the cities such as Antwerp and Ghent (though not Bruges) to take up its abode in the countryside, and especially in the villages of West Flanders that had been most affected by the linen crisis.

However, lacemaking is not a skill acquired overnight: it required teachers and schools. According to the historian of the Belgian lace industry, Pierre Verhaegen, ‘it was now that, under the influence of humble parish priests, of charitable persons, and some convent superiors, the lace industry suddenly took flight again. In the convents of the two Flanders and Brabant, children started to be taught to make lace; where there was no establishment of this kind then one was founded and soon there was hardly a convent in Flanders which did not possess a lace school. New female congregations of nuns sprang up and gathered around themselves the children of the villages where they were implanted.’[3] This describes the role of Duvillers in Middelburg: at his initiative local elites provided the funding for a lace school, and the staff was supplied by one of the new teaching congregations of nuns.

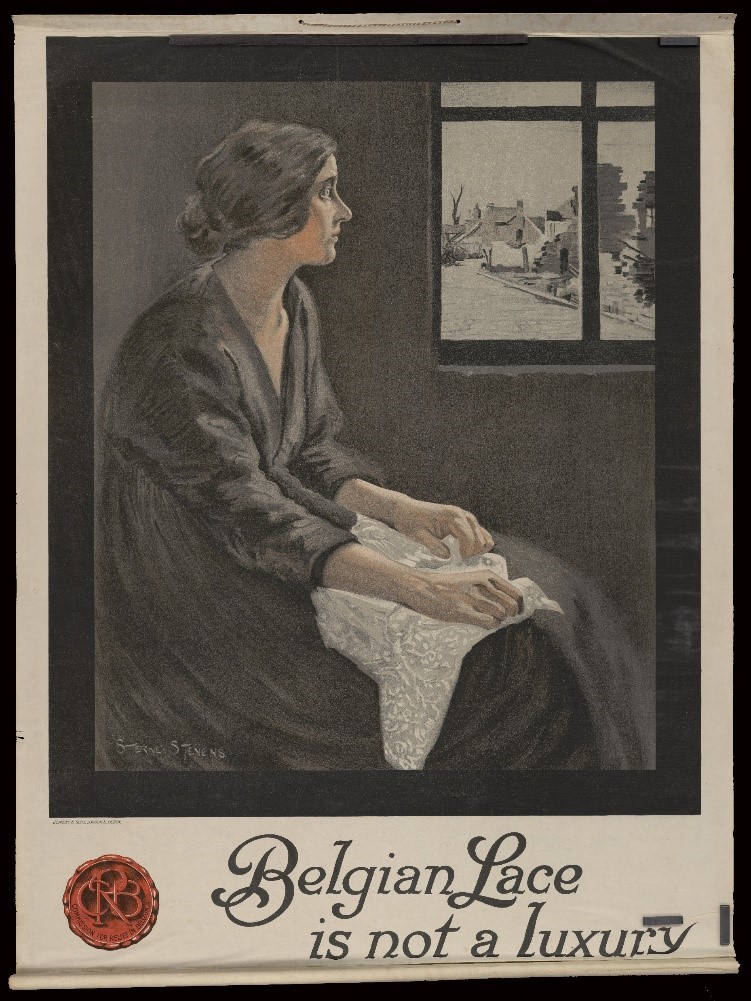

There are many ironies to this story. The political cleavage in the young Belgian state was between the liberals and the clericals. During the 1840s the liberals, who were largely French speaking and anticlerical, were the dominant party, but their response to the linen crisis, including the funding of the lace schools, required their collaboration with their political arch-rivals, the Flemish clergy. Later in the century, the creation of hundreds of lace workshops masquerading under the name ‘school’ created a new battlefront in ‘culture wars’ between clericals, liberals and, later, socialists. In the meantime, hundreds of thousands of young Flemish women were trained in a trade that effectively trapped them in poverty. For liberals, the failure of the clergy to provide a decent education for their charges, as well as the profits the Catholic Church drew from their ignorant, emaciated and tubercular lace apprentices, was a scandal. For socialists, the impoverished lacemaker became a symbol for ‘Arm Vlaanderen’ [Poor Flanders]: she was the personification of the entrenched misery which demanded radical action, such as the banning of domestic manufacture. But for the clergy and their supporters the homeworking lacemaker, trained by nuns simultaneously in religion and labour, was the epitome of domestic virtue.[4]

The battle over the lace schools was fought in literature as well as in the newspapers and the chambers of parliament, as we will see in future posts on the work of Johanna Courtmans-Berchmans, Virginie Loveling, Guido Gezelle, Stijn Streuvels, and Reimond Stijns, among others. All of these, however, had the opportunity to reflect after several decades on the success and failures of the lace schools: Duvillers was there at the start.

The Middleburg Girls School, for whom the 1844 volume of songs was intended, was Duvillers own project, or at least so claimed a song in which trainee seamstresses thanked ‘Our Pastor, who erected this school’.[5] This series of songs predates the onset of the linen crisis; nonetheless, the industry was clearly in trouble. In ‘The Song of the Spinners’, the speakers lament that ‘Wages are small, and living expensive/ There’s no butter on our bread’.[6] However, at that time lacemaking was only one of the replacement trades being taught: ‘I feel motivated / always to go to school. I learn lovely things there;/ I learn how to make nice lace;/ I sew, I knit,/ it is all profitable for me’.[7] Nonetheless lace was, to judge by the number of songs on the topic, the dominant occupation taught in the school, and Duvillers was clearly on a mission to promote it: ‘O blessed land!/ Where even small a small child’s hands/ Can sustain her parents,/ By playing, [she] can earn,/ By playing.’[8] Observers like Duvillers often thought of lacemaking as a form of play, an association made easier by the fact that in Flemish the terms are homonyms ― ‘spelen’ and ‘speldewerk’: ‘Here we play a game/ Where anyone might see us;/ The lace shines/ Like a genuine fairy art.’[9] Duvillers frequently used the term ‘toover’ – meaning magic or fairy – to describe lace, as did many other commentators on the industry.

By 1846, when Duvillers’ next volume of songs appeared, lace had become the single focus of Middelburg’s and many other schools across Flanders. The first song in the volume describes the situation as the linen crisis reached its peak. In years gone by father had sat to weave and mother to spin, and the loom and spinning-wheel together had saved the children from anxiety and grief as they could get their daily bread. But now that ‘Frenchmen wear no linen anymore’ (the French army had replaced its red linen trousers with cotton ones) the girls must go to the lace-school.[10] Yet despite the problems besetting Flanders, Duvillers’ tone in this volume is, overall, positive. In ‘Flora, the Bold Lacemaker’, for example, the eponymous heroine sings ‘Long live lacework! Farewell to the droning spinning wheel!/ I’ll follow the girls from the town,/ my fingers will play both large and small,/ and so Flora will earn her bread.’[11] Here, as elsewhere in these songs, the purchaser of the lace schools’ product is identified as ‘the Englishman’ or even ‘John Bull’. The lace school is clearly a developing proposition: one song describes the pristine building ‘on two floors!’, so much better than the ‘dark hole’ where they have been working up till now.[12]

This set of fourteen songs is essentially a promotional campaign to convince parents, and the apprentices themselves, of the benefits of the lace school. Duvillers highlights not only the monetary rewards but also that the girls can meet their friends, be warm and safe, and kept on the path of moral rectitude by ‘singing God’s praises’ and saying the rosary. However, they also sing other, secular songs ‘of the little weaver, or of the cat’ (probably references to lace tells).[13] In particular he dwells on the fun and games held on the Feast of St Gregory (12 March or 9 May, see our post on Geraardsbergen), the patron of lacemaking in East Flanders, when there would be a prize-giving attended by priest, the lord and lady from the chateau, as well as all the members of the philanthropic institute that supports the school, who will give out ‘big books clothes, hats and cloth’ to the pupils.[14] Later the whole school will go on jaunt to Ghent. In other songs Duvillers contrasts lacemaking to other occupations in agriculture or food production that might, on the surface, appear better remunerated. For instance he relates the cautionary tale of ‘Anastasia De Bal’ who threw her lace cushion in the fire and went to work for a farmer who taught her to swear like trooper. Although she earns a tad more, she is out shivering in the fields, her clothes are worn and tattered, and the work makes her hungry and thirsty (and implicitly food is costly). And of course agricultural work stops in the winter, and then she’ll be forced to live on potato peelings and even grass.[15]

A large number of Duvillers’ songs in this and the next volume are in the form of dialogues, and between them they cover many of the daily interactions experienced in and around the lace-school. For example, apprentice Mietje meets a gentleman on her way to the school, and when he learns that she is supporting her sick father as well as six children he gives her ten francs.[16] In the next song the priest visits the school to see how the apprentices are doing, and the lace-mistress gives a run-down on each individual’s progress, or lack of it.[17] The priest seems to be constantly dropping in on the school, either showing around other clergy who are interested in setting up their own school, or philanthropic gentry who might support the enterprise, or handing out prizes. Other visitors include the ‘koopvrouw’, the female intermediary who collected lace on behalf of the merchants in the distant cities.[18] In another song she is named as ‘Mevrouwe Delcampo’ from Bruges, while the teacher is frequently referred to as ‘Sister Monica’.

Both of these were probably real people, though so far I have been unable to verify this. Hopefully Duvillers was more careful to use pseudonyms to hide the identities of the numerous girls and young women who attended the school. Dozens are named, and in many cases in order to be upbraided. Wantje Loete, Cisca Bral, Mie d’Hont, Genoveva d’Hont, Barbara Kwikkelbeen, all had done something to annoy Duvillers. Most of these appear in the third, 1847 volume which is markedly more bad-tempered than its predecessors. In the winter of 1846-7 it appears that the children were being withdrawn from the school. Duvillers was particularly infuriated by the parents who, now their daughters had learnt the rudiments of lacemaking, kept them at home to save the few pennies that attendance at the lace-school incurred; or, just as bad, sending them out into the fields to do agricultural work. He warns Wantje Loete that once at home her cushion will stand empty because her mother will need her to look after her latest sibling, while her father will send her to look after the goats and pigs. Meanwhile she, and the other girls staying away from school, will never really master lacemaking.[19] The issue, though, was not entirely economic: for Duvillers the key success of the school was establishing religious oversight of all the young women in the parish and it was this moral authority which parents and some girls, were challenging.

All was not well in the school either: in the song ‘The School Mistress and the Foolish Mother’, the latter comes to complain that her daughter Mie has been beaten, and that she will take her, her stool and her cushion out of school if another finger is laid on her. The school mistress answers that no one has been beaten, she’s only dragged Mie into the middle of the school and made her kneel and pray because she is so lazy. And while the stool belongs to the family, the other tools belong to the school. ‘Don’t come back later and try to flatter us/ and ask us if she can [learn to] knit,/ Or even sew your clothes:/ Woman, this is no dovecot!’[20] However, the mistress’s protestations that no-one has been beaten are undermined by other songs in which she directly tells the children that she’s been instructed by the pastor himself ‘not to spare the rod’.[21] Perhaps this was the reason girls like Barbara Kwikkelbeen preferred hanging around in the street or wandering through the parish. In a fury over all this backsliding Duvillers declares ‘But as the poor are so pigheaded,/ Then I will not lift my hand to help them,/ And I’ll send them a punishment.’[22] If these songs in any way represent the priest’s actual relations with his parishioners, then it is plausible that it was this breakdown that brought about his removal from Middelburg, and not his obstreperous involvement in language politics.

As any regular visitor to this site will know, apprentice lacemakers sang while they worked. Duvillers frequently alludes to this custom, and even names some of the songs they sang, such as ‘Pierlala’. He presumably wanted his songs to be adopted by the Middelburg lace school as more suitable for future ‘brides of Christ’ (that is nuns, which was clearly Duvillers’ hope for at least some of the girls) than those currently in use, that is if his choice of tunes is indicative of what was being sung. Most of these seem derive from the theatre, such as ‘The Best is Good Enough for Me’, or ‘The Frozen Nose’.

Presumably also he hoped that his songs would be taken up in other lace schools, but is there evidence of this? Although Flemish lacemakers sang a lot of songs, not many of them were actually about lacemaking itself. If anything their songs served as an imagined escape from their task. Duvillers’ songs, on the other hand, offer a detailed picture of life in a lace-school, of how the children interacted with each other, of the injunctions of the lace-mistress, of the various visitors during the day… the kind of nitty-gritty quotidian commonplaces that are a goldmine for the social historian but unlikely to excite a singer. This mundane character, and the highly localized references, made me think that, as songs, Duvillers’ work had probably fallen rather flat.

However, at least one of Duvillers’ songs did become a lace tell, and a version was still sung a century after publication. In 1948 Magda Cafmeyer published a series of articles ‘From Cradle to Grave’ about life-cycle traditions in Bruges and its immediate surrounding villages. She included, under youth, lace tells, and offered one that she herself had heard.[23]

It is worth seeing

Us making net (i.e. lace)

For the bonnets

of the young ladies of the city.

The finest lace

For our customers

Enriched with flower and leaf

one link, one lattice opening made

Wantje’s lace rests unsold

Isabelle gets

Ten franks the ell (the unit used for measuring lace, about 70 cm)

But she’s a fierce one

She doesn’t even look up

Her fingers twirl

The sticks (bobbins) roll;

They seem to dance before one’s eye.

O wonder, especially if anyone sees it,

But this tough one (‘schrimmer’ in Cafmeyer’s tell, ‘grimmer’ in Duvillers’ song), hardly ever leaves the house.

Just like magic!

Says boss de Lye (an unidentified figure),

As he quickly leaves the school.

Farewell to the field

The farmer and the baker

How fast and how wide-awake (I am)

And I also get a little wage

I work here peacefully

By my sister

I sit here warm and clean.

Unknown to Cafmeyer, these are two verses, albeit slightly rearranged, of one of Duvillers’ Speldewerksters-liedjes which appeared in his first, 1844 collection. In his own way, he had contributed to the craft culture of Flemish lacemakers.

[1] For a fuller biography of Father Duvillers, and detail of his works and his legend, see J. Muyldermans, ‘Constant Duvillers (1803-1885). Zijn leven en zijne schriften’, in Verslagen en Mededelingen der Koninklijke Vlaamse Academie voor Taal- en Letterkunde (1928): 148-202, and F. van Es, Pastoor Constant Duvillers, Folklorist en folkloristische figuur (Ghent, 1949).

[2] G. Jacquemyns, Histoire de la crise économique des Flandres (1845-1850) (Brussels, 1929).

[3] Pierre Verhaegen, Les industries à domicile en Belgique: La dentelle et la broderie sur tulle (Brussels: Office du Travail, 1891), vol. 1, p. 49.

[4] We will return to this political debate in future posts, but for liberal/socialist critiques of the Catholic Church’s involvement in the lace schools see Guillaume Degreef, L’ouvrière dentellière en Belgique (Brussels, 1886) and Auguste de Winne, À travers les Flandres (Ghent, 1902). Although Pierre Verhaegen’s father, Pierre-Théodore Verhaegen (1796-1862) was the effective leader of the Belgian liberals and anticlericals, and at the forefront of the battle over education (students at the Free University of Brussels – free of Catholic influence that is – still celebrate ‘Saint Verhaegen’s Day’), he himself took a more positive view on the Church’s lace schools.

[5] C. Duvillers, Twintig Nieuwe Liedjes, ten geebruyke der Meysjesschool van Middelburg, in Vlaenderen (Ghent, 1844): Naeystersliedje ‘O! dank zy onzen pastor:/ Hij heeft de school gesticht’.

[6] Duvillers, Twintig Nieuwe Liedjes: ‘T Liedje der Spinnetten ‘Den loon is kleyn; en ‘t is duer leven;/ Er ligt geen’ boter op ons brood’.

[7] Duvillers, Twintig Nieuwe Liedjes: Huys-liedje ‘ ‘k Voel mij gedreven/ Om altyd school te gaen./ Daer leer ik fraeye zaken:/ ‘k Leer nette kantjes maken;/ Ik naey, ik brey,/ ‘t Is al profyt voor my’.

[8] Duvillers, Twintig Nieuwe Liedjes: Kantwerksters-Liedje ‘O zalig land!/ Waer ook een’ kinderhand/ Zyn’ ouders onderstand,/ Al spelen, kan verschaffen,/ Al spelen, ja!’

[9] Ander Kantwerksters-Liedje ‘Wy spelen hier een spel/ Waer ieder moet op kyken;/ Dat speldenwerken schynt/ Een’ regte tooverkonst.’

[10] C. Duvillers, Liedjes voor de Kantwerkscholen, Gevolge door de Spreuken van baeske Van de Wiele (Bruges: Vandecastell-Werbrouck, 1846): no. 1: ‘Toen ik nog een kleyn boontje was,/ Deed vader ook in ‘t linnen,/ Terwyl ik in een boekske las,/ Zat moeder daer te spinnen; En ‘t spinnewiel en ‘t weefgetouw/ Bevrydden ons van druk en rouw,/ Wy konden ‘t broodje winnen.’

[11] Duvillers, Liedjes voor de Kantwerkscholen (1846): Flora, of de moedige kantwerkster ‘Vivat het spellewerk! Vivat!/ Vaerwel het ronkend spinnewielken!/ Ik volg de meysjes van de stad,/ ‘k speel met ving’ren, kleyn en groot,/ En zoo wint Floorken ook haer brood.’

[12] Duvillers, Liedjes voor de Kantwerkscholen (1846): no. 6: ‘Er ryst voor ons een’ nieuwe school,/ Ze zyn al de tweede stagie,/ Sa! Dochters, schept maer goê couragie:/ Haest krupt gy uyt uw donker hol.’

[13] Duvillers, Liedjes voor de Kantwerkscholen (1846): De Schoolvrouw, den pastor en de dry vreemde heeren ‘Sa! Kinders, zingen wy eens dat/ Van ‘t Weverken of van de Kat’. Neither reference can be clearly identified as weavers and cats are both common characers in Flemish folksong, but two popular lace tells were ‘Daar waren vier wevers’ and ‘De katje aan de zee’.

[14] Duvillers, Liedjes voor de Kantwerkscholen (1846): Den Pastor en de Schoolvrouw ‘En, dan kom ik afgetreden/ Met den heere van ‘t kasteel,/ En mevrouw, en al de leden/ Van ‘t weldadigheyds-bureel,/ En wy geven groote boeken,/ Nieuwe kleedren, mutsen, doeken,/ Al die braef is krygt zyn deel.’

[15] Duvillers, Liedjes voor de Kantwerkscholen (1846): no. 14.

[16] Duvillers, Liedjes voor de Kantwerkscholen (1846): Den Heer en het schoolkind.

[17] Duvillers, Liedjes voor de Kantwerkscholen (1846): Den pastor en de schoolvrouw.

[18] Duvillers, Liedjes voor de Kantwerkscholen (1846): De Koopvrouw en de zuyster.

[19] C. Duvillers, Liedjes voor de Kantwerkscholen en Spreuken van baeske Van de Wiele (Ghent, 1847): Wantje Loete.

[20] Duvillers, Liedjes voor de Kantwerkscholen (1847): De Schoolvrouw en d’onverstandige Moeder ‘Brengt u ‘t meysken in ‘t verdriet,/ Threse, en kom dan later niet/ Schoone spreken, en ons vleyen,/ En ons vragen of ‘t mag breyen,/ Of eens naeyen aen uw kleed:/ Vrouw, ‘t is hier geen duyvenkeet.’

[21] Duvillers, Liedjes voor de Kantwerkscholen (1847): De Zuster en de Schoolkinders ‘Den pastor heeft my streng bevolen/ Van in de beyde kantwerkscholen/ Daer op te letten, en de roê/ Zoo niet te sparen, lyk ik doe.’

[22] Duvillers, Liedjes voor de Kantwerkscholen (1847): Genoveva d’Hont ‘Maer al den armen ‘t zoo verstaet,/ Dan doe ‘ker maer myn hand van af,/ En ‘k jon ze hem, de straf.’

[23] Magda Cafmeyer, ‘Van de wieg tot het graf III: Dat was de jeugd’, Biekorf 49 (1948): 206-7.